This dispatch appeared in S01 Episode 2, along with Nisu, or I Want My Male Idol to Be My Female Lover by Ting Lin. Cover illustration by Krish Raghav.

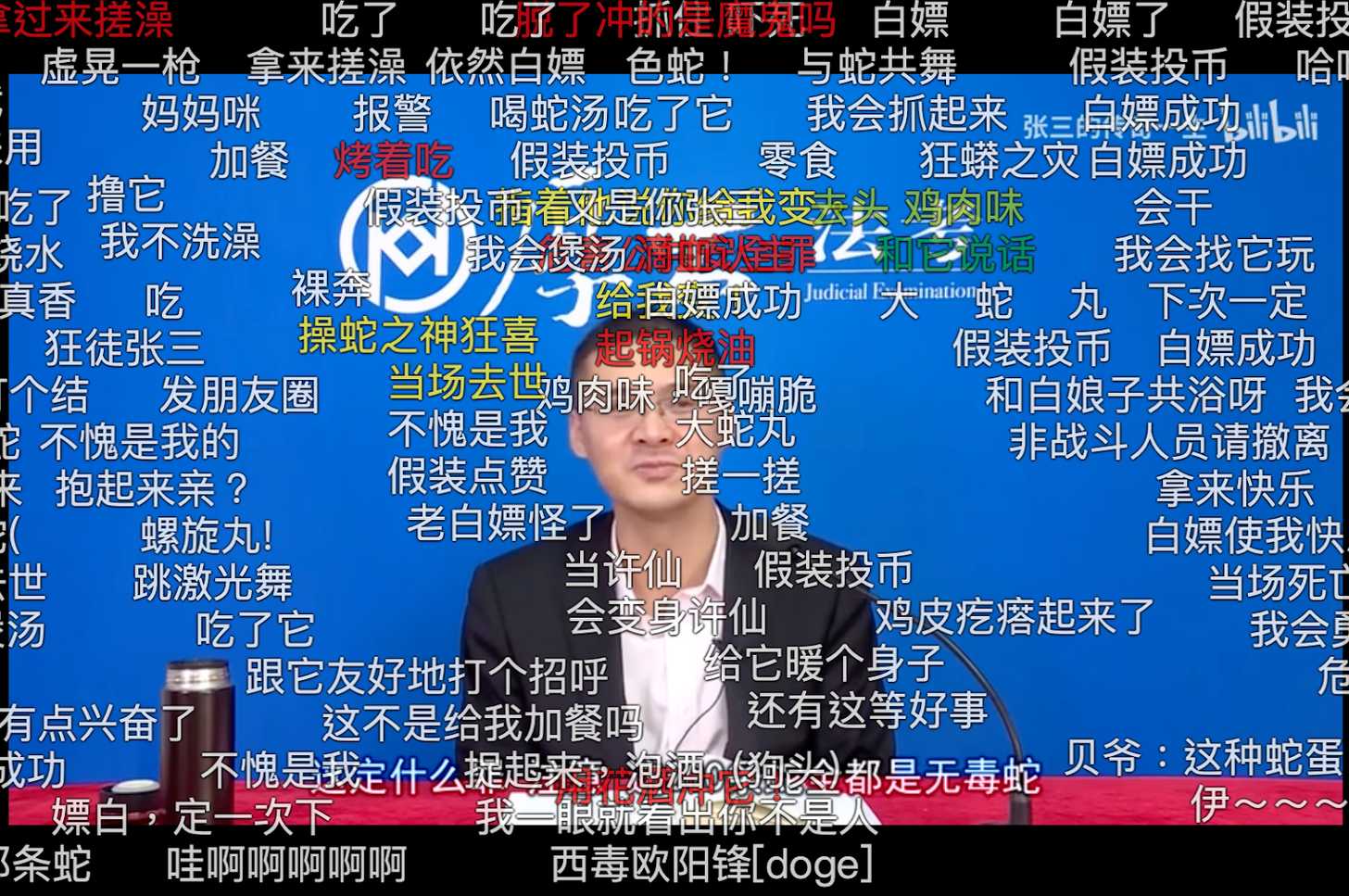

Yan: Criminal law professor Luo Xiang (罗翔) has over 13 million followers on video platform Bilibili, but few of them are there to prepare for China’s crazy tough bar exam. They’re there for entertainment.

Luo opened his channel in March 2020 and racked up his first million followers in days. Even before going official, his video lectures recorded for a bar exam prep school were circulating widely, finding an unexpected audience outside aspiring lawyers.

Usually around 5 minutes long, his videos are a cross between Michael Sandel’s “Justice” lectures and the courtroom stories of videogames like Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney. Each features a surreal case study, delivered like a deadpan stand-up comedy set. The protagonist is the diabolical Zhang San (张三, the Chinese equivalent of “John Doe”), as famous and beloved as its creator. In a video about “endangering public safety,” Zhang San releases 985 vipers into a park to celebrate his son’s admission to a top university. If the snakes are not venomous, Luo Xiang smirks, Zhang San walks away free. The absurdity of these stories is intentional—lure you in with an easy laugh, then drop the heavy intricacies of Chinese criminal law.

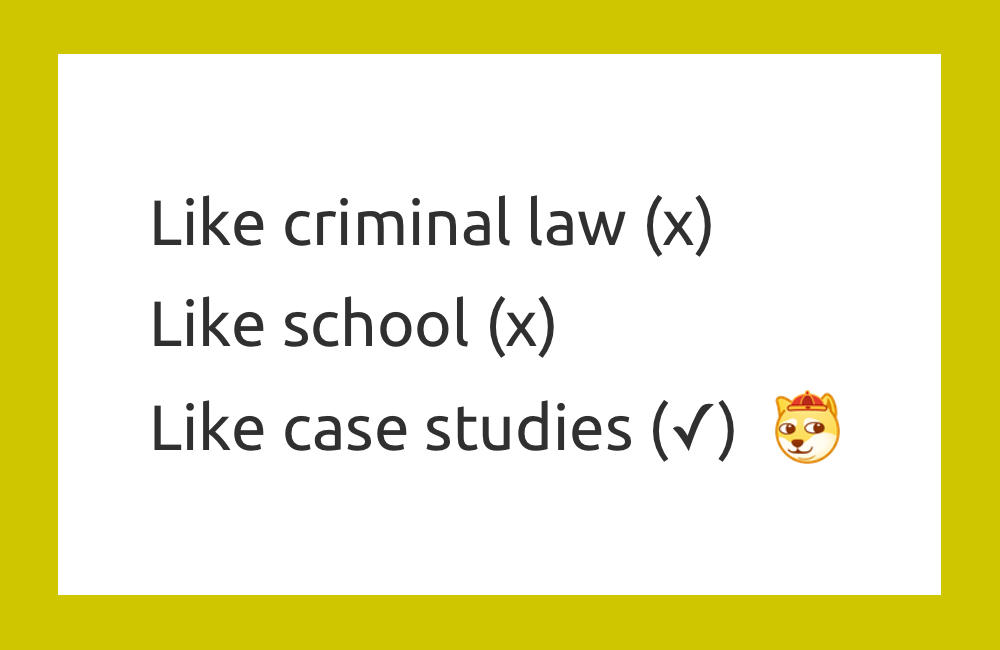

One of the most-liked comments on Bilibili, parodying the multiple choice questions that end most Luo Xiang videos, goes:

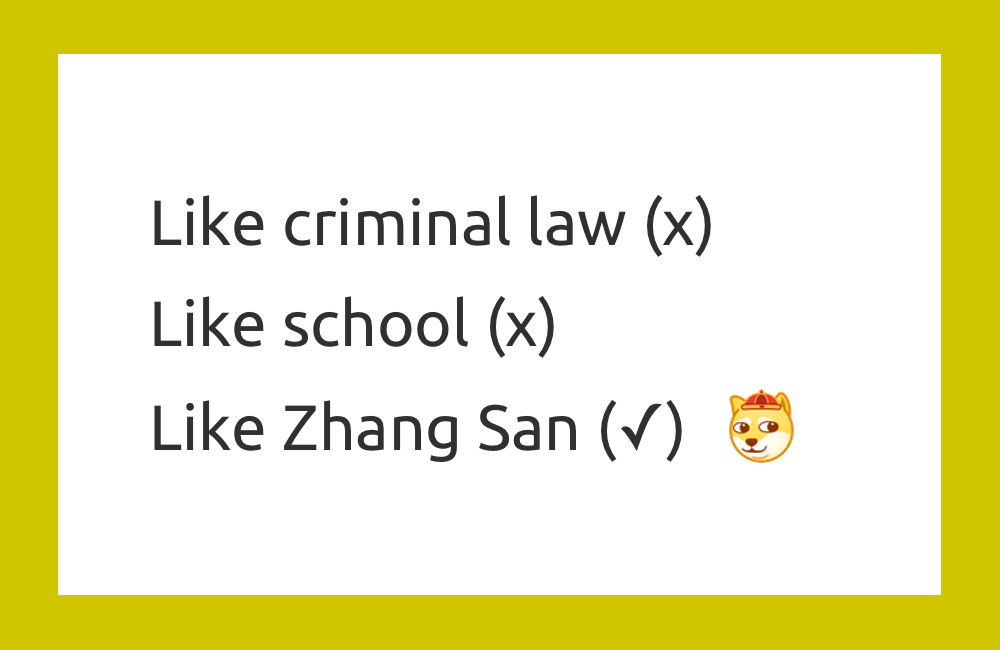

Another replies:

Simon: If I can backtrack for a bit, why would one release snakes to celebrate their child’s accomplishments?

Krish: Presumably Zhang San learning a trick or 985 from “Cool Mandy.”

Yan: Luo Xiang is meme gold. A starter pack would include “365 ways for Zhang San to die,” a video edited by a die-hard fan who put together sound bites from Luo’s lectures describing imaginary scenarios where Zhang San dies from murders, incidents, and murders-turned-incidents. Fans mix Luo Xiang clips with popular memes, including this insane super cut that situates Zhang San within almost every major Chinese internet phenomenon of the last few years (keywords: Duang, Jinkela fertilizers (金坷垃), That scene from Downfall (元首的愤怒), and so many more).

Luo Xiang’s peers like Shang Jiangang (商建刚), a lawyer-turned-judge in Shanghai, applaud Luo’s exceptional skill in translating boring legal language into funny stories that everyone can consume. Shang added, “If you prepare for the bar exam watching Luo Xiang’s videos, it’s going to be very slow and ineffective.”

Indeed, Luo seems uninterested in dwelling on “correct answers” or points on quizzes. He’s not satisfied with merely telling a good joke either. What draws many, myself included, is that behind the facade of a hilarious criminal law lecturer, he cares deeply about justice and the legal system. In one case study, a victim who buys adulterated milk powder demands compensation and is wrongfully jailed for blackmail. Luo gets passionate: “For individual rights, everything that is not forbidden is allowed! For public power, everything that is not allowed is forbidden!”

Like Michael Sandel, Luo always connects hypothetical scenarios to bigger legal or philosophical questions. He repeatedly emphasizes that law should be grounded in people’s lived experience and common sense. It should respond to the times, and not fossilize into a system for pure “rationalbro” logical reasoning.

On September 8, 2020, Luo Xiang was caught up in an absurd controversy. He shared a quote on Weibo, “Cherish virtue and don't become a slave to honor, because the former is eternal, but the latter will soon disappear.” This was the same day that respiratory disease expert Zhong Nanshan received China’s highest state honour, the Medal of the Republic, for his contribution to China’s fight against COVID-19. An online mob attacked Luo for indirectly calling a national hero “a slave to honor.”

They were methodical criminal law acolytes. They dug up Luo’s Weibo posts from years ago as “evidence” that he was “unhappy with the system” all along. The irony here is that a law professor who taught the presumption of innocence was assumed guilty from the get-go. As the trolls dug up more evidence, Luo first tried to explain that there was no connection between his post and the medal award. But this wasn’t a Zhang San-style case study for deliberation. Realizing that to explain himself would be futile, he quit Weibo.

——

Krish: I’m reminded of the “desktop documentary” Forensickness, which makes this connection between how fandoms online can become “forensically-minded” towards objects of culture, and that same spectatorial attitude, contaminated by the possibility of hidden meanings, can became an analytical frenzy directed at real people.

Yan: I wonder if there’s a connection with the increasing amount of “archives” for people to dig up now: a Weibo early adopter would have more than a decade of posts on the platform, potentially open, for everyone to examine closely. Before real-name registration was the norm, all people could do was renrou (人肉, “human flesh search engine,” a form of crowd-sourced information gathering that often included doxxing). The “archival detectives” today have more primary sources on which they can base their speculations about a person’s political viewpoints or motivation.

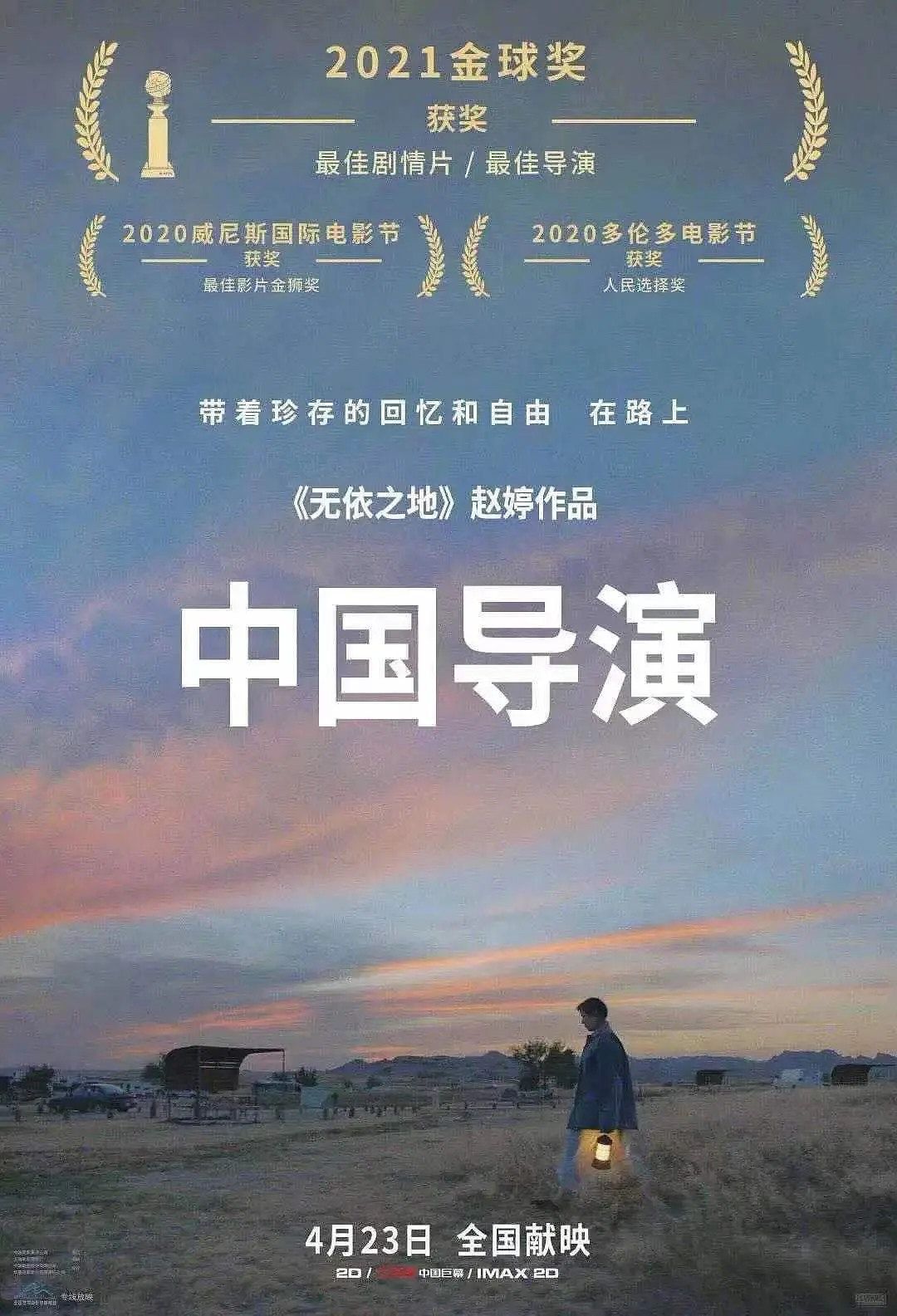

Tianyu: Yeah, and we’re seeing this kind of toxic discourse more often these days. Chloé Zhao, who won a Golden Globe for her film Nomadland, was criticized for her past remarks about China (“where there are lies everywhere”) and her own identity (“The U.S. is now my country, ultimately”), both dug up from old interviews. China has also asked broadcasters to downplay the Oscars, for which Zhao is nominated.

Yi-Ling: I’m struck by how both online attacks—of Luo’s criminal justice videos and of Zhao’s Nomadland that Tianyu mentions—also feel starkly different in tone and tenor than the human flesh search engine accusations of the early Weibo days of 2012—which some often dub its “Golden Age.” Whereas the Weibo takedowns of the past were more cacophonous, this feels more like a one-noted mob: deviate from the status quo, and we’ll roast you no matter what.

——

Yan: So Luo, a paragon of public engagement, had to disengage. Fortunately, he remains active elsewhere, on Bilibili and through media interviews. He’s fond of quoting Greek philosopher Epictetus:

Remember that you are an actor in a drama of such sort as the author chooses… If it be his pleasure that you should enact a poor man, see that you act it well; or a cripple, or a ruler, or a private citizen. For this is your business, to act well the given part; but to choose it, belongs to another.

It surprised me that someone as influential as Luo, who single-handedly made criminal law part of popular culture, believes that what he does is predetermined by a force he has no control over. The road to viral fame can feel dangerous, as scale brings with it this loss of control.

The nuance of Luo Xiang’s lectures and his public voice, that line he perfectly straddled between case study absurdities and the complications of criminal law, fell victim to the cruelties of the public sphere in China today. Hopefully, this will become just another Zhang San teaching moment. After all, what can he do but “act well the given part”—that of a criminal law professor.

Yan: For more inspirational quotes from Luo Xiang, I recommend this mix with soothing piano music in the background.)

Tianyu: I know no one asked for this, but here’s a nisu version of Luo Xiang:

Yan Cong is a Beijing-based photographer. She is not the guy in Jilin who carries a rock on his head, despite Google’s insistence.

Simon Frank is a writer, translator, and musician in Beijing. He is embarrassed to say he is a DJ, but is, in fact, also a DJ.

Krish Raghav is a comic-book artist in Beijing. He is the second picture in the galaxy brain meme.

Tianyu Fang is a writer who grew up in Beijing. He spends most of his free time eating Lanzhou beef noodles and subtweeting.

Jaime (bot) is a critic and translator in Beijing who lives in Dongcheng and works in Chaoyang. She is also a contributing editor at Spike.

Yi-Ling Liu is a writer in Beijing. She likes to wall-dance—both online and at the climbing gym.