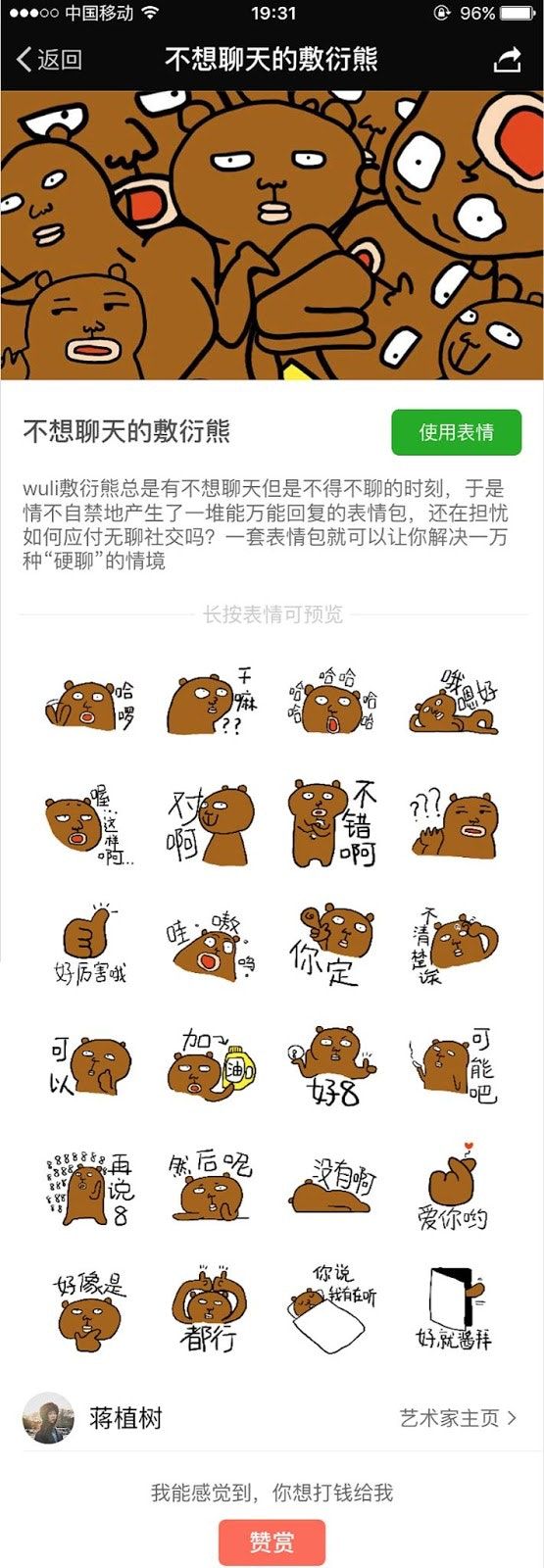

This dispatch appeared in S01 Episode 6, our two-part exploration of WeChat sticker packs, along with Is YimaoRen Okay? Is Anyone Okay? by Yan Cong. Cover illustration by Jiang ZhiShu; all images used with creator’s permission.

Krish: Fuyan-kuma (敷衍熊, lit. “half-hearted bear”) is my favourite WeChat sticker series. It’s classic “Weird WeChat”—a bit dark, a bit violent, a bit too gleeful in its dark violence. It’s inspired by the “gross cuteness”of kimo-kawaii, a semi-autobiographical diary of ennui and tiredness starring the titular half-hearted bear. I like using it at work to quietly signal my alienation and lack of enthusiasm.

A Fuyan-kuma sticker pack, to me, is somewhere between experimental narrative comic, flash poetry, mood board, and meme. Over time, as Fuyan-kuma’s skin tone has lightened (for “commercial reasons,” according to the creator), the series has also reflected the shifting mood among middle-class young urban professionals (the sticker’s primary demographic) from playful rebellion to weary resignation.

I chatted with creator Jiang ZhiShu (蒋植树) on WeChat. She talks about Fuyan-kuma’s origins, inspirations and future. This interview is translated from Chinese and edited for clarity.

Krish: Hi! Could you introduce yourself?

Jiang ZhiShu (she/her): Well, I’m the creator of Fuyan-kuma (敷衍熊). This is my creator alt: 蒋植树 (“JiangPlantsTrees”). I chose this because my birthday is on Arbor Day. I’ve been drawing Fuyan-kuma for five years now—it started as a WeChat sticker pack in July 2016. I quit my job in September last year to work on illustrating full-time. Now I mainly rely on my Taobao store for a living. It's so miserable. I don't know what else to say lol.

Krish: How did that first sticker pack happen? What was the “sticker scene” like at the time?

Jiang ZhiShu: I’d just finished grad school, and WeChat’s Sticker Gallery was open to user submissions. I literally just drew a set within an hour and uploaded it.

I guess I found all the existing stickers at the time too cloyingly sweet and too nauseatingly cute. I prefer something more “low”—a kind of slapdash ugliness. I also hate chatting online, so I wanted to create a sticker pack that reflected my hatred.

On WeChat, I think the popular sticker set at the time was Tuzki (兔斯基), and since I was studying in Hong Kong, I was familiar with a lot of the weird and wonderful Line stickers.

Krish: Is there a Fuyan-kuma “cinematic universe” that you keep track of? Are you consciously building a “world” or a narrative through these stickers?

Jiang ZhiShu: There’s no structure to the world...he’s just a slob otaku bear (肥宅的一个小熊) who dislikes social pressures and lives a slob otaku life. He’s surrounded by archetype friends that we can all recognize—simps, dweebs, “green tea bitches” (绿茶婊), and queers.

Krish: What is the process of getting a sticker pack on the WeChat platform? Have you ever had to change a sticker, re-do a drawing, or take a sticker pack down?

Jiang ZhiShu: They have a separate platform for sticker creators. They used to be really slow to audit and approve, but I never really encountered any big problems. Not sure if they staffed up or streamlined the process, but it’s really fast now. You can get a pack uploaded in 2-3 days.

You can get certain phrases or internet slang flagged and rejected, then you have to write an email to explain to them what the expression means, or find similar examples that have already been approved on WeChat. I faced that with a “草“ (cao, lit. “grass”) sticker in my third pack. It um...caused some concerns...but I (successfully) explained that it means “lol” in Japanese slang, and not...you know. (Note: “Cao” is an all-purpose homophone for “fuck”.)

Krish: What’s the most popular Fuyan-kuma sticker?

Jiang ZhiShu: The first pack is still the most popular, because that one is a bit more demented, more unique.

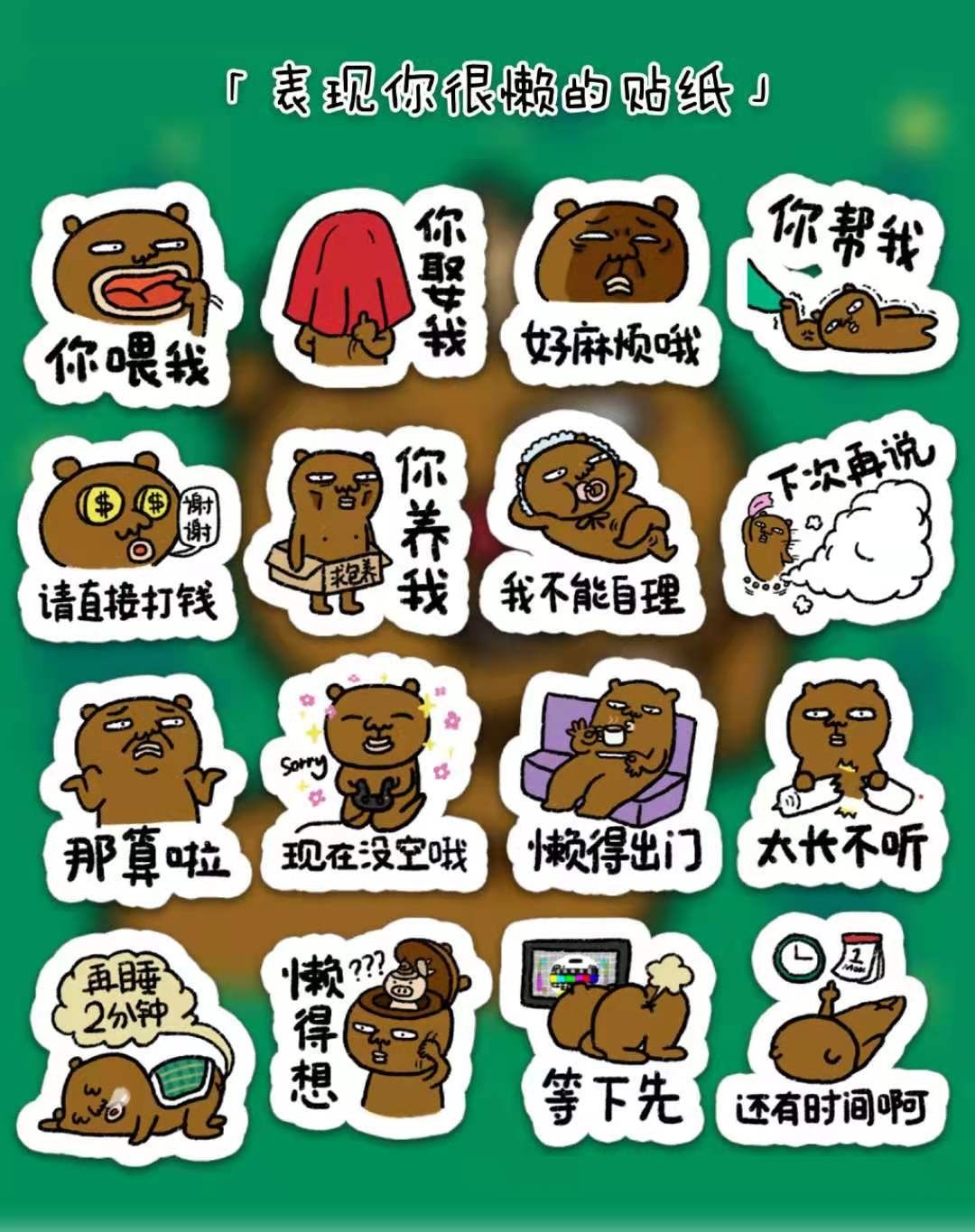

Krish: I feel like your next milestone was in 2017, when you released the “Fuyan-kuma’s Late-Stage Terminal Laziness” (敷衍熊懒癌晚期) pack. This one is my favourite, and it really captured this rising mood of “sang” 丧 culture and laziness-as-resistance in China. Could you talk about the inspiration behind this pack? What were you reading or watching at the time?

Jiang ZhiShu: I was still working then, and yeah, we were deep into sang culture. We were all trying to find the space to focus on ourselves, and seeing an emptiness within. I wanted to try and capture a “Fuyan-kuma” approach to workplace life, to maybe show that young people today can legitimately choose to “reject” what they felt was unimportant.

The dark side of workplace culture was definitely an influence. In their jobs, people are often deploying academic-paper levels of rigor to frivolous problems like “increasing engagement on a Kuaishou channel.” It’s darkly funny, but then they’re also suffering the constant PUA of toxic workplace leadership. I think this “rejection” comes from that combination —this mismatch of intelligence and education with the reality of what many jobs require.

Simon: Interestingly, "PUA" has picked up a somewhat different meaning in Chinese "office" English—not literally referring to "Pick Up Artists" all the time, but to emotional exploitation, quasi-brainwashing, and gaslighting in the work environment more generally. Of course, the way the term has travelled and evolved reflects the same virality though which stickers are transmitted. Also, I have colleagues who pronounce it "pua" :)

Krish: A few months ago, you put out a sequel of sorts: the “Fuyan-kuma at Work” (敷衍熊打工篇) sticker pack. This one has a lightness to it that feels like you’re reflecting back on your old workplace life rather than actively suffering through it.

Jiang ZhiShu: I think the post-95 and post-00s generation are much more reluctant to work overtime or to indulge in work-circle socializing. They dare to refuse these things. So where “Terminal Laziness” seems to say you *can* resist—that you don’t need to be enthusiastic at work all the time, that anger is justified, that you can foster a little resistance in your heart—much of that is normalized in work culture now (think “996”), which is reflected in the “At Work” pack.

When I drew these, I was watching a Japanese drama called "I Will Not Work Overtime, Period“ and reading this Taiwanese comic diary called “Can I Not Go To Work?” (可不可以不要上班).

I think, since it's becoming an aging and low birth-rate society earlier than us, Japan has a maturity and courage in addressing youth ennui that feels “ahead of its time” in China. For various reasons (SARFT, “societal norms”), China hasn’t quite excavated and completely unpacked the minds of its own young.

You can find a lot out there that’s “positive energy”, but those of us who’ve been repressed/depressed for a long time are relatively under-represented. It’s probably why all these insane (and dark) Bilibili videos go viral often—it’s a form of cathartic venting for feelings running underneath.

Krish: Do you see yourself as part of a community of sticker artists? Do you communicate with them, or exchange experiences and tips?

Jiang ZhiShu: I do, but I also have a social phobia. It’s very difficult for me to take the initiative, so I usually just wait for others to contact me. There are groups, but I’m more of a lurker, really. I’ll send a few stickers, shitpost in my mind, and go back to drawing by myself.

Krish: Do you have any artistic ideals or creative goals you want to achieve as an illustrator? Do you see this as a “career”?

Jiang ZhiShu: I’m neither professionally trained nor very good at “illustrating,” so I prefer to just be called a “sticker maker.” I guess my goal is to create an “IP” (intellectual property) that is popular, and to that end I’m extending the Fuyan-kuma world outwards beyond stickers—to Douyin short videos, Taobao merch, etc.

It’s a career, of sorts. I’d love to keep drawing, and maybe put out a book, given the chance. Books aren’t very profitable now, but it’s a dream for every creator to be able to publish at least one. I’m going to sign with a company that manages sticker artists, so that’s a step up.

Krish: Can you talk about “the sticker economy,” such as it is? What are the routes to economic security for a sticker maker?

Jiang ZhiShu: It's very difficult to make a living with stickers alone. You have to create a consistent IP, ideally one you own yourself, which then exists across platforms and forms—Taobao, Weibo, Douyin, WeChat, Xiaohongshu. It’s a precarious market because the competition for IP is intense. There’s a lot out there, and only the IPs that can continuously produce high-quality works or constantly go viral can succeed. So creators need to have one foot in the “fan economy” to go viral, and another in rapid prototyping to drive...well, consumerism around new products.

Krish: Why do you think the environment for creation and commercialization is so hostile to creators?

Jiang ZhiShu: Hot online products are more often not driven by well-known IP. They can be viral phenomenon, such as the “Kitten that Carries Everything” (万物皆可举的小猫), or the Douyin-famous “Ugly Fish Mask” (绿头鱼头套) These aren’t well-known IP with big capital infusions like Line Friends, but are a kind of “SEO” manipulation that rely on catchphrases, memes, or mentions by influencers. Cabbage Dog (菜狗) is a good example—an older illustration that became a hot-selling product due to buzzwords in the news. Capturing fickle attention isn’t easy, and when you’re focused on going viral, you can’t really go deep.

So there’s an adjustment I have to make with Fuyan-kuma—from a semi-autobiographical, narrative character to a visually-appealing platform for “products” that can sell well.

Krish: You have close to 100,000 Weibo followers, as well as fan groups on Weibo and WeChat. How do you run your fan community? Do your fans influence your work?

Jiang ZhiShu: My fans actually built the groups themselves, because I didn't have the energy to manage it at that time. They call themselves “celery.”

Krish: ...celery.

Jiang ZhiShu: Yeah. Since I’m called “Zhi Shu”, the same name as a character in a Taiwanese drama (based on a Japanese show) called “It All Started With a Kiss,” (惡作劇之吻) they named themselves after Xiang Qin (湘琴), the female lead who has a crush on Zhi Shu in the show. But they swapped the “qin” character with the word for “celery” (芹).

I’m really thankful to them. They help me manage the fan ranks and keep order. They also inspire me a lot, pointing me to trending topics or widespread pet peeves. I learn a lot from them.

I guess “resonance” is one of the most important qualities for a WeChat sticker maker. Only sympathetic, truthfully observed work can win everyone's recognition and approval, so having an attentive fan group like this is such a blessing. I send works-in-progress to the group sometimes, to get feedback, to learn what they like and dislike.

Krish: And finally, what other WeChat stickers do you use these days?

Jiang ZhiShu: I’m still drawn to the niche, “ugly” ones. I save a lot of meme-related stickers, which aren’t very easy to use in ordinary chats. I like Teacher Guo (郭老师), Brother Yaoshui (药水哥), and the classic “Panda Head” biaoqing.

Krish: Do you have a personal favourite Fuyan-kuma illustration?

Jiang ZhiShu:

Simon: Talking about “sang” culture makes me think about something I’ve wondered about recently. It may be a very “my own generation is the best/worst” perspective, but if discourses about China often talk about the speed of growth and an atmosphere of entrepreneurship, isn’t there an inverse to that growth? The faster things come together, the sooner people might want to opt out. Starting to twitch involuntarily as I recall the countless poorly-considered references to accelerationism and misappropriations of Mark Fisher’s writing that I’ve had to translate, but should we ask if an accelerated rise also results in accelerated entropy? To put it another way, it took Europe and America around a century to get from capitalist industrial takeoff to SoundCloud rappers, and China only 40 years.

If you haven’t, consider subscribing to Chaoyang Trap, a newsletter about everyday life on the Chinese internet. It’s a regular, usually fortnightly, exploration of contemporary China, one important niche at a time. We’re interested in marginal subcultures, tiny obsessions, and unexpected connections.

Paid subscribers get access to our special deep-dives and premium issues!

Krish Raghav is a comic-book artist in Beijing who has one-too-many 我很好 stickers.

Jiang ZhiShu is a sticker maker based in Beijing (but not Chaoyang). You can buy Fuyan-kuma merch on her Taobao shop.

Simon Frank is a writer, editor, and musician/slob otaku human based in Beijing.