This dispatch is the entirety of S01 Episode 8. Cover illustration by Lisha Jiang.

In the house this week: Caiwei, Lisha, Diaodiao, Yi-Ling, Tianyu, Yan, Jaime, Ting, Krish, Simon, and Henry.

Jaime: Welcome to Episode 8.

A friend shared a meme recently that goes “Chinese parents wait their whole lives for their children to be grateful; Chinese children wait their whole lives for their parents to apologize.”

Growing up with a younger brother, I have been cursed to witness all the ways men have failed their sons. Gender essentialism notwithstanding, it is natural for us to want to learn from people who look like us.

So while structural inequalities, misogyny, and the patriarchy still make it hard and annoying to be a woman in Chinese society, on a personal empowerment (or even representational) level, it is not hard to notice signs of change. All around us—pop culture, media, social media, fashion, advertising, “content,” literature—there are so many more ways for women to see and hear how they ought to be. (Whether or not these products or ideas are capitalizing on the “feminist” zeitgeist, at least the possibilities are expanding.) Similar cultural education simply isn’t as ubiquitous for guys.

If I were a 22-year-old boy who just graduated from college, applying for my first job, want a girlfriend but don’t know how, and I don’t really have anyone in the family to look up to, where do I look instead? What can I do so that I don’t end up like my shitty dad?How do I know who I want to be?

Krish: This episode came out of the realization that we knew very little about these “playbooks” for how to be a dude.

Our understanding of the global “manosphere” (everything from incels and GamerGate to soyboy discourse and red-pilling) felt inadequate when considering the state of Chinese masculinity. So Caiwei had to heroically stumble down some cursed rabbit holes to bring you this deep-dive.

We profiled three influential men of the Chinese manosphere, rough equivalents to Joe Rogan, Tim Ferriss, and Naval Ravikant. While they are not considered mainstream figures, their stories and courtship of an urban middle-class audience form one chunk of the millennial masculinity iceberg. One that illustrates some of the larger stakes of what this generation of men are facing.

Read till the end. Our outro song this week tells a story of what happens when fragile masculinity turns dark, and how a resilient feminism responds.

The Dusk of Chinese Masculinity

By Caiwei Chen

Caiwei: Is masculinity at its breaking point? Outside China, the question has dominated public discourse for years, as waves of crises and feminist critique unravel patriarchy’s pervasive toxicity. Traditional masculinity, an ideal characterized by athleticism, stoicism, aggression, and dominance, seems to be waning as the sole ideal for what men should be. At least in popular culture, a more androgynous, gender-fluid vision of masculinity, represented by men like Timothée Chalamet, is going mainstream.

Something similar is taking place online in China. In the past year, feminist icons have sprung up from different social classes and backgrounds, without corresponding male equivalents. Recently, China's Education Ministry even published plans to counter the so-called "feminization" of young men, calling for a return of “the spirit of yang” (“masculine energy”) in younger generations. Underlying the state’s anxiety is a deeper crisis: Men are confused and lost. Who are their new icons if traditional male idols like “Wolf Warrior” Wu Jing 吴京, and figures like TV host Zhu Jun 朱军 or author Xiong Peiyun 熊培云 (both accused of harassment in #MeToo cases) have become out-of-date and cannot stand up to scrutiny?

I started to look into the question, and discovered three interesting examples from urban China—taking baby steps towards a more expansive idea of masculinity. Steve Shi, Derek Huang, and Zhang Xiaoyu are three figures on the Chinese self-help scene, who each appeal to different groups of modern Chinese men. But they share one thing in common: they all tap into a certain core anxiety men are experiencing, be it spiritual, interpersonal, or moral.

Let’s start with the spiritual.

12 Rules for Steve Shi’s Life

Steve Shi (史秀雄), 35, has had a surreal character arc as a thought leader—a former Jordan Peterson disciple who reinvented himself as a liberal icon.

Based in Shanghai, Shi is a psychotherapist, podcaster, and writer. On social media, he is also a charismatic self-help guru, a feminist ally, a queer ally, and a promoter of “healthy masculinity” to China’s lost young men.

The bulk of Shi’s online presence is in two podcasts: Steve Says (Steve说), which features longform conversations with friends, and Man Li (Man立), a podcast on modern masculinity in China that he co-hosts with dating coach Wu Guangmin (仵广敏). Steve Says, in particular, is his calling card—started six years ago and now a magnet for China’s social media royalty. It’s directly inspired by The Joe Rogan Experience.

Shi arrived on the podcasting scene in 2015, much before the medium’s popularity took off around 2018. He started off either monologuing or interviewing his friends (episode 2 of Steve Shuo features his college classmate), gradually expanding his roster to fellow creators (episode 4 features a friend who blogged about “getting a boyfriend in 30 days”), and eventually to a popular show for prominent online figures. The show is currently at 238 episodes.

There’s quite a range: in episode 172, Steve talked about how he wants to hug all his fans in Wuhan after the pandemic, while episode 208 features Liu Min of popular indie band Re-Tros shooting the breeze about her love of pop psychology. Long-term listeners could really feel invested in Shi’s trajectory of change—from a clueless straight bro to an empathetic husband. He’s opened up about overcoming stereotypes, acknowledged that crying doesn’t make him less of a man, had his thinking overturned by guests on the show, and encouraged men to practice compassion towards their female partners and friends.

With 6 million podcast listens on the Ximalaya platform and over 200,000 Weibo followers, Shi had already built a sizable audience before his big break: Jordan Peterson. In January 2018, Peterson trended on Chinese social media after his interview with Channel 4’s Cathy Newman. “Confrontation between white-left feminist host and the hardcore reasoning of Jordan Peterson” (白左女权主持人与硬核理性乔丹·彼得森巅峰对决) read the title of a widely circulated video on Weibo with Chinese subtitles. This was around the time when Weibo’s feminist discourse was making its way into the mainstream, still largely uncensored—a time when the #MeToo movement began to spread across China, and a time when the now-prolonged war between progressive feminists and nationalist misogynists broke out.

Shi, who’d taken two classes with Peterson as a student at the University of Toronto, played a key role in China’s Peterson craze alongside Ma Mengjie, known as Big Heart Paipai (大心脏排排) on Weibo, around this time. A study-abroad student based in Germany at the time, Ma made it her personal mission to introduce Peterson’s philosophy to a Chinese audience. The Chinese title was catnip to Chinese conservatives: a hatred of political correctness, disillusionment with western progressives, and a fixation on “hardcore” rationality. Ma’s translation also boosted the popularity of the word “baizuo,” which directly translates into “white left,” and has since been appropriated as a reactionary weapon, even making it into the global alt-right’s lexicon.

Shi presented himself as a moderate voice in the feminist-Jordan Peterson debate, pointing out where he agreed and disagreed with his professor. As he wrote in a Weibo post (translation by me), “Cathy Newman is a terrible interviewer and she misrepresented Peterson's opinion. Peterson is not against transgender people or gender pronouns, but the governmental enforcement of them. Social justice warriors in the west have seriously damaged North America's freedom of speech, and that's a context a lot of Chinese netizens are not familiar with.” Shi also pointed out Peterson's limitation: “Evolution and biology are indeed not Peterson's expertise, so some of his remarks might seem immature.”

To Steve, Peterson’s social critique was specific to the West’s problems, but his self-help content was far more universal. Shi actively reached out to publishers to translate Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life into Chinese, which eventually landed him a translation deal with Cheers Publishing in Beijing. The book sent Shi on a speaking tour all across China, where he met Wu Guangmin, his future co-host on Man Li.

Another Peterson stan, Wu resonated with Shi almost immediately. To the (then) young and puzzled Wu, discovering Peterson was like getting a daddy he never had—a strict yet forgiving figure, and a role model for masculinity. Wu’s fixation on Peterson led him to write a master’s thesis on the Peterson fandom, in which Wu confronted the absence of a similar figure for most male Chinese youth.

The idea of starting Man Li came naturally for the two—a conversation about what masculinity really means in China today. “Traditional masculinity places little emphasis on individuality and independent thinking, that is something I am extremely critical of,” Shi wrote in an email. “I’m also very critical of men’s lack of knowledge of intimacy and sexuality, which seems to me a key factor in men’s health as well as gender equality.” Shi believes that masculinity is, like “femininity,” not a monolithic experience, and Man Li’s content and guest list tries to reflect that belief.

In Man Li, Steve and Wu discussed every item their female counterparts would discuss in an edgy feminist social critique podcast, from representation in pop culture, to queer awakenings, to a playbook on modern dating. They have invited guests such as Zhu Junyi 朱浚溢, a visually impaired mental counselor; Wei Wei 魏伟, a professor of queer theory; and Harry, a gay illustrator who mostly paints male genitals. “Masculinity (n.), plural.”

How does Shi square these circles? How can someone who built his influence backing Peterson, then rode a wave of feminist backlash on the Chinese web, now be an ally to the marginalized? Is he a rare voice capable of straddling China internet’s ideological divides, or another opportunist that tries to ingratiate himself to both sides of the conversation?

Shi positions himself as a neutral, “rational” voice. This means that on Weibo posts and podcast episodes, he can back his senpai Peterson’s refusal to use gender-neutral pronouns, while showing allyship to feminists and the queer community. He can criticize social justice warriors in the west for “suffocating freedom of speech,” but also use his platform to amplify the voice of Xianzi, a survivor and plaintiff of a landmark #Metoo case in China against Zhu Jun. He advocates for self-discipline, speaks against plus-size trans model Jari Jones’ appearance in CK campaign, and encourages men to embrace their vulnerability—all seemingly in the same breath.

Tianyu: It's particularly interesting how social conservatives in China (and elsewhere) often pose themselves as a centrist voice. They aren’t keen to defend social injustices; rather, they acknowledge the problems and then move on to say the solutions are too radical, that they’d rather sweep the issues under the rug.

Caiwei: As host and podcaster, Shi is a natural—he’s sincere, eloquent, engaging, respectful, clever, yet approachable. In episode 207, while discussing takeaways from past relationships with fellow podcaster Meng Chang, Shi admitted to his own shallowness when replying to Meng’s arguments. “Men are dumb,” he said. “I’m so lucky that my partner is a resilient woman who would challenge my macho views.” Above all, his humility and willingness to change his mind lets his guests’ points of view shine. He is the nice person among the smart people, and the smart person among the average people.

“My position is more dialectical,” Shi wrote in emailed replies to my questions. “I do not take sides. I perhaps can be said to be a centrist or moderate, because I know from my psychological counseling work that most issues are very complex. Taking sides and harsh criticism can not change anything.”

But can’t they? Shi’s own evolution bears this out. “At first [in 2018] I found my perspectives more conservative, including being more critical of political correctness, but I am slowly reconciling the balance of conservative and progressive,” he said. Shi is still pessimistic about the dynamic of gender discourse on social media today, believing more substantial change in gender equality should come from the policy level.

Diaodiao: This is intriguing. Is he going for a “armchair online critics can’t create real change” position, a “women’s rights needs to enter the chat'' hot take, or a “we need to actively participate in shaping policy” pivot? This could be interpreted as radical or conservative, and knowing Steve, the ambiguity is probably the point.

Caiwei: Speaking to Shi, you can tell he’s still thinking things through, willing to change, to reconcile the contradictions of the personal and the political. Self-awareness is the thing he thinks Chinese men lack the most, and his solution feels both important and a bit of a cop-out: “start a conversation.”

But is that conversation merely running in circles? My last question for Shi was one he asks his guests on Man Li all the time: “Who’s your role model as a man?” For Shi, that used to be Peterson, but now he hopes that he, himself, could be that role model for younger boys. He recognizes that the journey of becoming this ideal could be a long ride. “I know it doesn’t happen overnight, and I am ready to take time to accumulate and prepare,” Shi said. “In that sense, I’m trying to be a role model for masculinity at large”.

——

Jaime: What if this "neutral and rational referee" is Shi’s ideal of masculinity? Someone who can "moderate" his way through difficult conversations, putting controversial ideas on the table without offending any sides, a benevolent authority figure?

Krish: Shi sounds like he’s one personal crisis away from selling protein supplements. I’m reminded of Hussein Kesvani’s analysis of male Youtubers, where he points out that their disparate (“moderate”) politics are often by design, because despite all the “advice” and “tips”, it’s a fundamentally reactionary view of the world. To paraphrase Kesvani:

What [Shi] offers through his content are seemingly achievable goals - and crucially, changes that his listeners can adopt without thinking about their position within an increasingly decaying and disorientated society.

Simon: As someone who also studied at the University of Toronto, I have to say it’s been a bizarre and frightening journey to watch Jordan Peterson go from an odd professor whose over-enthusiastic students and teaching assistants your friends would tell you to avoid, to a dangerous global phenomenon. Learning more about Shi, it is surprising, even pleasantly so, to see how some of what he does might have a positive influence. And yet, it does seem like a single bad experience or simply the winds of the market could send him spiralling into a far more negative territory.

Back to Peterson, I’ve been shocked by friends in China, mostly in “alternative” cultural spaces, being into his writing—which I think speaks to a more universal truth that just because someone shares a certain identity with you, doesn’t mean you share all the same values. In the Chinese context it reminds me of a good thread Krish had on Twitter on how different struggles are often kept segmented and self-contained within subcultures. Also, perhaps for people such as Shi, Jordan Peterson and a field like queer theory are both new cultural influences they were exposed to while living abroad, thus allowing them to be grouped together for supposedly neutral study despite their inherent contradictions. I’m well aware that such a viewpoint ignores local lineages and activism, but might it be how some people are thinking about things?

Some semi-useful lessons learned from five years in a small music company in Beijing:

— Krish Raghav (@krishraghav) November 29, 2019

1. The sites of progressive / radical values in China are not where you expect. Not all punk rockers and club heads are activists - they're just as likely to be Han supremacist nationalists.

Yi-Ling: As Simon says, lately, it seems like neat ideological alignments in China have begun to fall apart. You can be a militantly nationalist queer activist, just as you can be a chauvinistic champion of free expression. I anticipate seeing more people who are intellectually fluid, and difficult to pin down, in the years to come. The trickier question will be to determine whether they are ideologically flexible or morally spineless. (It’s a fine line between the two.)

Derek Huang: Tinder Guy Reacts to Feminism

Derek Huang is the Tim Ferriss to Steve Shi’s Joe Rogan. Derek, 24, is a ByteDance employee who creates dating guides for men. Although unaware of each other, Steve and Derek’s trajectories overlap considerably. They both studied abroad and spent considerable time obsessed with questions of “attraction” and dating chops. They both consolidated their takeaways into prescriptive content that they (over)share. Both met their romantic partners on Tinder and made it a model for relationships in general. They’re both podcast guys.

But while Steve discusses, at length, the importance of making thorough radical psychological changes, Derek focuses on “quick fixes” that work immediately.

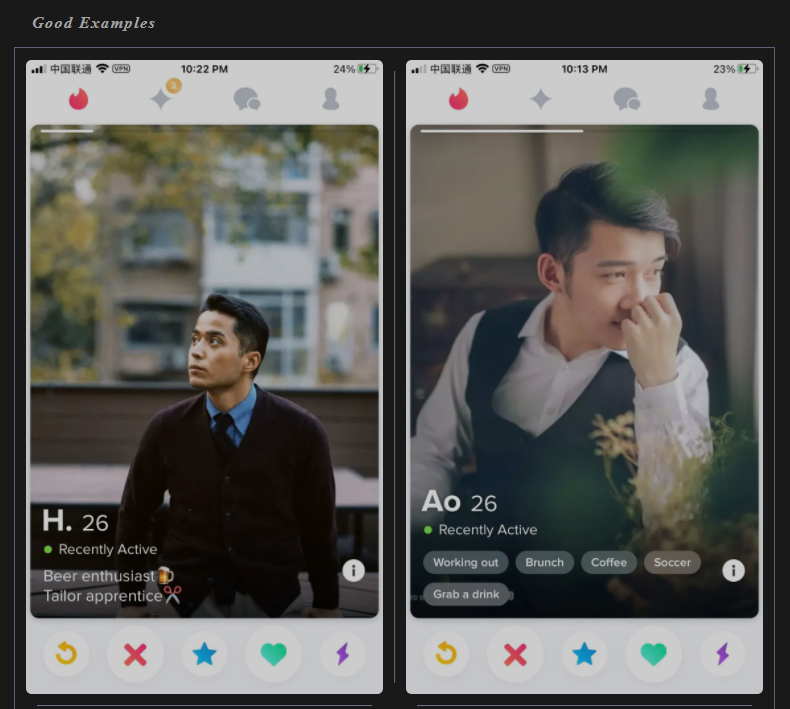

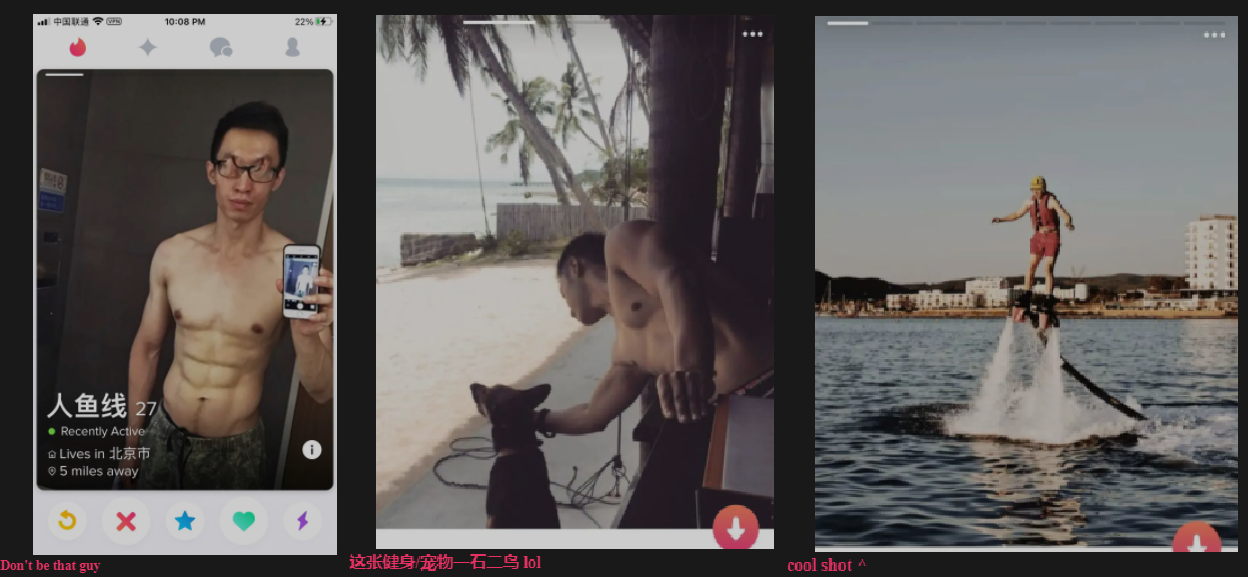

“Use a front-facing picture as the lead on your Tinder profile.”

“Subtlety is sexy.”

“Make your bio as cool as this:

This is advice from Derek’s Ultimate Tinder Guide for Men, one of his most popular works. “Casually show your hobbies in your pictures—hiking, working out, reading, pets... Basically, the epitome of your weekend life. Avoid selfies. If you have to, limit it to one. Use at least one full body shot to make your profile look more legit. Don’t go overboard by using too many professionally shot pictures—smartphones can take really good portraits these days.”

Derek’s guide is about as long as an average Chaoyang Trap episode, divided into 7 parts: Self-Assessment, Profile Setup, Swiping, Opener, Chat, Getting a Date and “More.” It’s a good textbook I would recommend to any clueless online dating beginner, a balance of theory and practice peppered with both dos and don'ts. It’s an unapologetically urban middle class in voice and tone.

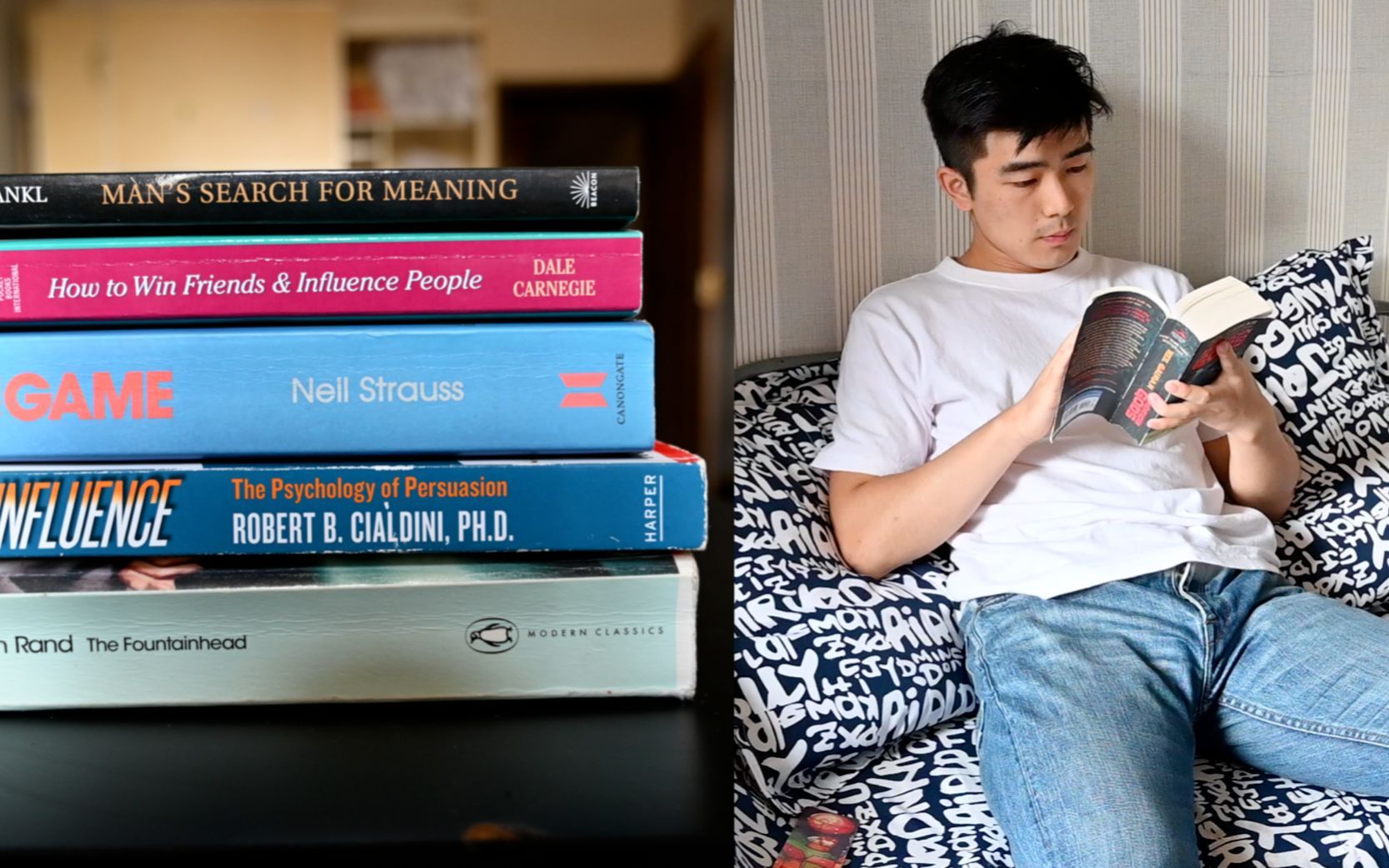

Derek is active on Weibo and Jike, posting dating-related thoughts and “takeaways” from reading English-language motivational books. His personal brand on WeChat and Bilibili is Derek in Puxi (迪克在浦西), where “Derek,” transliterated as “Di-ke” 迪克 and Puxi 浦西, a district of Shanghai, are pun-y euphemisms for...well, just read it out loud.

Surprising no one, he is also a crypto and podcast guy, casting regularly to Bilibili and TikTok, and co-hosting a podcast named Xin Xue Lai Chao (心血来潮, lit. “on a whim”) with his girlfriend Ellen. A typical episode has a title like “How to tell if your crush likes you back.”

Derek is charming and self-aware. As an exchange student in Europe in 2017, he started seeing patterns in cross-cultural dating. “The biggest difference Chinese guys have with their western counterparts is not in appearance, but in the life they are able to create with women,” Derek told me in a phone interview. “Western guys are more individualistic, more respectful to women, and are overall way better at socializing.”

This collision of cultural values Derek experienced first-hand got him started on a journey of exploring different dating experiences, and that began with improving his own sex appeal. “Getting girls was almost all I thought about those days, and change only came naturally, both physically and mentally,” Derek said. He later turned his experience into a series of Bilibili videos called “Dating with Derek.” The first two episodes are titled “Dating the French beauty I met at a poker table” and “The 3 hours I spent with a Hungarian girl in a castle.”

Derek’s idea of becoming a digital content creator originated from learning from multiple female friends that their experience swiping men on Tinder sucked. Women complained to him that most guys don’t even put in basic efforts on dating apps, and Derek can relate, after spending some time “undercover” on Tinder with a female account. It did not take long for Derek to sum up the three biggest problems with Chinese men on Tinder: bad pictures, too goal-oriented, bad conversation skills. Now he wanted to help them.

Derek is meticulous with details. He does tons of research, makes the effort to summarize succinctly, and even shares “best practices” and examples for his fans to learn from (and steal).

Apart from tips and dating “methodologies,” Derek also shares analysis about gender and dating dynamics in urban China today. “Most Chinese guys look sloppy but actually have too much unearned confidence, while women are the opposite. Most women look appropriate, but actually have many insecurities under the table,” reads one of Derek’s posts. “In a relatively higher quality pool, females have the upper hand in the dating phase, while power shifts to males when it comes to talking about marriage” goes another.

I have to admit the truth I recognize in his posts despite the discomfort of framing gendered social dynamics as some kind of “cheat code” for dating. Everything is a “game” to master, and he’s playing along. When I interviewed Derek over the phone, my question came naturally: is this stuff just good old-fashioned pick-up artistry?

Derek replied that he’s thought long and hard about this question, even recording a podcast episode about it. Derek points to the lack of sexual education in China’s education system and the toxic social expectations of men as the dominant reasons PUA, as a “method,” has its appeal. It provides, he says, a quick fix to the anxieties of Chinese men, but crosses the line when the attraction is based on deceit and disguise. “I have to admit that the status quo is indeed this bad, that’s why I have to provide the hand-on-hand quick fixes, so that at least they can fake it till they make it.”

Derek added that a large portion of his audience are women, who constantly forward his posts to their male friends. He suspected that the reason is that guys, even though the actual target audience of his content, have too big an ego to accept that they need help from another guy. I find this observation intriguing, when similar content to his created and consumed by women are so commonplace that no one would question their intent.

“Our fathers couldn’t provide any constructive guidance to us,” Derek said, channeling strong Fight Club energy. “We are a generation (of men) caught between the gap of empowered women and lost men.” He showed reserved support for feminism when I asked, quoting the oft-repeated “Men of quality are not afraid of equality” line. For Derek, he prefers to focus on just the “quality” part of that equation, making dating or relationships “easy games.” “It could be this way for most guys too, if they’re willing to put their ego aside and learn,” he said.

Yan: I’m thinking about the fact that these influencers have a big following among women, who don't see these dating methodologies as problematic, and pass them on to male friends. It's like a feedback loop where women will internalize this worldview and act accordingly to please men (or to gain an upper hand?), and recruit even more men to adopt it, which altogether reinforces the imbalanced dynamics between men and women in dating.

Henry: I literally cannot imagine being handed something like this in the US, where it’s pretty commonplace for women to pre-empt men in bars trying to “run routines” on them by saying, “Hey, have you heard of The Game?” Point being, stop thinking 100 pages of How to Talk to Girls for Dummies will serve as a replacement for vulnerability, empathy, courage, etc. Pick up artistry welds the defeated egoism of self-help culture (you won’t change the structure, so change yourself) with a cynical, zero-sum vision of dating (conquer women or be conquered).

It bears saying that both are misguided responses to real social ills: How to Win Friends and Influence People, Dale Carnegie’s ür-text of bootstrapping entrepreneurship, was published in the depths of the Great Depression, when most Americans felt utterly abandoned by their government; and men, as various feminists have pointed out, are also a casualty of masculinity—one is not born, but hazed into, a frat boy. A real fix would require parsing, challenging, and reforming gender roles—and I think the despair of ever accomplishing this is what animates PUA.

On the other hand, context is important: the sheer number of women on Tinder in China I’ve seen whose profiles say “not going to fall for your pyramid scheme,” “stop posting fake pics” (not catfishing—totally fake pictures), and “don’t want to see your nipples in every photo” suggests that online dating really is horrible here—that it’s not fuckboys, but literal con artists and antisocial creeps that these women are worrying about. So while I share Yan’s worries about internalized sexism, I also wonder if the bar is so low that even Huang might be seen as progressive.

Zhang Xiaoyu: Vicodin for the (Leveraged) Soul

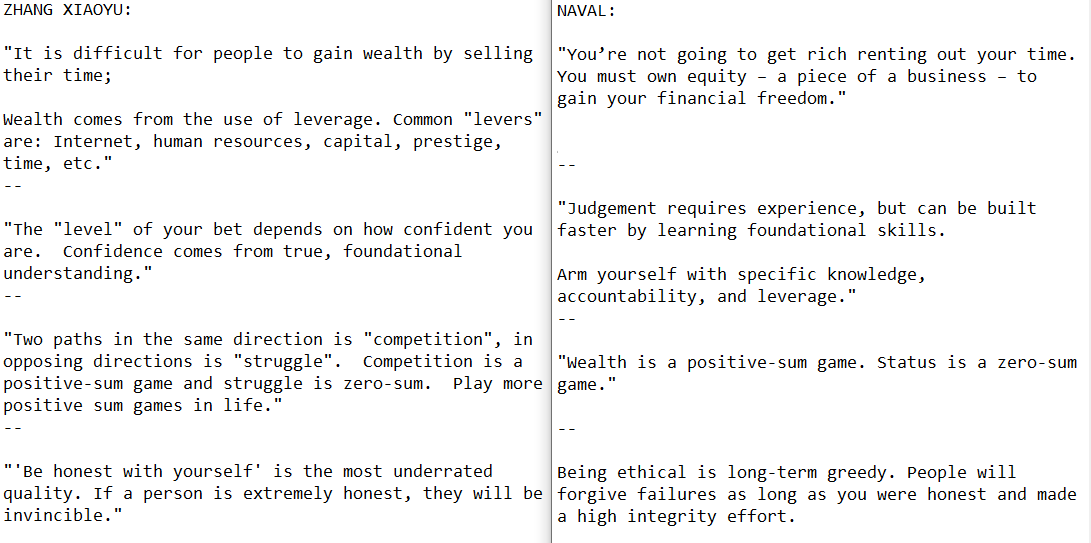

Zhang Xiaoyu (张潇雨, “VicodinXYZ” on Weibo) is China’s answer to Naval Ravikant. While the lie-down youth of China find solace in the reluctant idol Lelush, Zhang is the idol for the “lean-in” crowd—the ones who hope to rise to the top within China’s hyper-capitalist system, above the spiral of involution. Like Naval, VicodinXYZ is half-investment guru, half-philosopher-king. He has the same sharp writing style that hints at profundity, and the same celestial, transcendent halo that sets him apart from all other life-advice-giving finance bros.

Like almost all internet opinion leaders who emerged in the 2010s, Zhang, a former Goldman Sachs equity analyst, gained his initial following on Zhihu, an ask-the-internet-type forum. Zhang was a prolific advice-giver and his answers, shared widely, were usually short and sharp. His insights spanned everything from wealth creation and spirituality to entrepreneurship.

Zhang’s shtick is finding the thinking patterns behind everyday, mundane decisions and unpacking them in pithy sentences. Zhang is critical of a lot of social norms, considers himself a defender of classical liberalism, and often calls on fans to reflect on their biases. Zhang on consumerism: “You never know how a glance at a Nike ad influences your decision to buy a pair of Nike shoes years later. Just as the balance of medieval time was established by the contradictions of god and the devil, the balance of our society is established by the dichotomy of consumerism and the revelation of it. Consumerism has become the new god and myth of our time.”

In response to a popular question on Zhihu, “Can one achieve financial freedom solely by trading on the stock market?” Zhang answered: ”Yes, you can. But people who can usually know they can do it very early on, without asking anyone else.“

This is a typical Zhang response, deeming the question itself insignificant by challenging how it is raised while alluding to the disparity of endowed intelligence. Zhang claims inspiration from the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, who is famously obsessed with the difficulties of language when people communicate. As a result, he is conditioned to read between the lines of questions directed at him, throwing a deadly “but what do you really mean...” back at the answer seeker’s face. The seeming profundity goes hand-in-hand with a preachy snobbery. Oftentimes that includes pointing out the mediocrity and shallowness of the thinking that led to the question. Under the question “What's more important for success—natural gifts or hard work?” Zhang replied: “Resisting the urge to think of questions in dichotomies is a key step to any insight in life.”

Zhang has an advanced poster’s brain. He is the kind of person who draws take-aways from everything he experiences. Tennis is a chance to muse on strength, power, and spirituality. A day spent looking up techno led to Zhang musing that the genre has a kindred spirit in Buddhist recitation. A bizarre experience mistaking a sip of coffee for Coke enlightened Zhang on the bugs of “The Great Simulation” we might all live in.

His straightforward, often cold, hard rules prove particularly appealing to a subgroup of modern males, aka tech nerds, partially because of the business and financial glossary in his pocket.

“Look at the risk-reward ratio to improve the return of your life.”

“Design the structure of your life like it's a product.”

“Surround yourself with better people to increase the probability of good incidents in your life.”

These are enough to get you started on a Zhang-ian spiritual journey.

Zhang’s fandom is especially cult-like, organized around his podcast De Yi Wang Xing (得意忘形, lit. “carried away”). His podcast is structured as an unscripted monologue, which he calls “a media project advocating for the pursuit of individual freedom and truth”—basically an extended version of Zhang’s social media posts, packed with western popular science references and his ubiquitous life reflections.

Fans call Zhang “teacher” (张老师), and their reverence for him is heartfelt. “I can’t help falling crazy in love with the show, as if I have found the thing that corresponds to my soul,” posted Zhihu user Haynel. Haynel said the process of listening to De Yi Wang Xing was “a journey that helps you become yourself, a quest of epiphanies, and the most ideal form of education.” The feeling is echoed by other listeners. Zanna, a Beijing based tech worker, said she sees the ideal of education in Zhang’s podcast.

To officially be a part of the fan group, you have to first join a group chat through the namesake Weibo account “The De Yi Wang Xing Sorting Hat.” The Harry Potter reference reveals the dynamic of his fandom: a college-like self-improvement community with access to special knowledge about the world.

David, a tech worker based in Nanjing and one of the admins of the sorting hat group, told me that he started listening to Zhang back in 2017. The entire organization, sorting hat included, is independently started, operated, and administered by fans themselves. Between 2017 and 2018 was the heyday of the group chat, seeing offline meetups taking place frequently all over China.

Judging from the mission of his podcast, it’s hard to believe that Zhang is also known for running “Zhang Xiaoyu’s Personal Investment Class,” an audio masterclass best-seller on Dedao that has sold over 110k copies on the platform. In his own words, “one cannot become rich by selling their time by the hour.”

For Zhang and his followers, the world isn’t meant to be interrogated but rather leveraged for personal gain. Relentless self-improvement is their remedy to the complexities of China’s modern life. But can self-improvement create change? Zhang’s principles may bring order to chaotic lives, but his brand of self-help is merely Vicodin for the soul—one that temporarily stems the pain without treating the cause. How is his ideal of liberalism attainable, short of a structural change in society or a rebalancing of individual wealth?

Zhang has never claimed to have the answers. His approach, which one can justifiably critique as pandering to already-privileged urban elites, is a targeted pursuit of what he calls “personal spiritual freedom.” “There is no such thing as willpower,” goes one of his principles. “Instead of trying to improve willpower—create a better environment for yourself.”

There is an allure to Zhang’s consistency. He is a prudent optimist and reserved idealist who can navigate capitalism’s lost children through the market maze. He provides a long-lost spirit of futurism, the same promise that makes Elon Musk a masculine icon among tech bros. In investment lingo, he is the champion of long termism, a strategy in business that prioritizes good-faith investment in long-term growth and sustainability (“wealth is a positive sum game”). This business strategy then also becomes an ethical framework, when the time frame is stretched to as long as it possibly can: financial value, in Zhang’s mind, eventually overlaps with human value.

Zhang’s outlook for the future taps into something Chinese men have been long deprived of (unless you buy in, wholesale, to the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation"). For this generation of women who could see themselves represented by role models emerging from all walks of life, the future is a communal and more equitable society. In contrast, for men, the future seems alienating and isolating. But for fans of Zhang Xiaoyu, there is a path to a future that is both personally enriching and communally meaningful, within reach as long as we invest, reflect, and play long-term games with long-term people.

——

Henry: Zhang’s "can't be rich selling labor" and "consumerism is our god" quips do feel like class analysis—reminds me of Chomsky's point that business elites actually understand and sort of even agree with Marx's categories, but work bitterly to prevent the proles from gaining the same knowledge. Surely the appeal of this whole scam is that it's 98% snake oil, 2% sober analysis, and customers are impressed by that 2% because it's still better than the 996, work-until-you-die message.

Diaodiao: These three guys represent the three kinds of high school “guy ideals” most Chinese men never age out of: the prudish but secretly people-pleasing student body president (Steve), the bad kid who can get girls and also teach you how to get girls (Derek), and the genius top-of-your-class guy who constantly reminds you that your IQ is inferior (Zhang Xiaoyu).

Krish: Virgin. Chad. Speedrunner.

Yan: Political correctness PUA. 迪克-in-浦西 PUA. Intellectual PUA.

Tianyu: That’s it for episode 8! If you enjoyed this, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription, or forward it to a friend by hitting the shiny button below! All of our revenue will go towards paying contributors on time and supporting writers. We also welcome feedback, story ideas, and cute animal GIFs via email (hello [at] chaoya.ng) or Twitter (@ChaoyangTrap).

Krish: Next time: Taobao, magic, and JUSTICE CRAB.

Outro music this week is a story about trash men and fire women. A few weeks ago, a female student at Beijing Foreign Studies University (北外) was date-raped by a fellow student. They’d matched on Tinder, and he slipped something into her drink while catching a concert. Later, she discovered that he was in the university’s “hip-hop club,” so she recorded this absolute scorcher as a diss track outing him. When released, the song, and the perpetrator’s name, trended on Weibo, and the issue has since danced around deletions and censorship to stay visible online.

Tianyu: Bye!

Caiwei Chen is a writer, journalist and podcaster. She reclaims ownership of her femininity by getting back to the kitchen.

Lisha Jiang is a Hangzhou-based illustrator and comic book artist.

Tianyu Fang is a writer who grew up in Beijing and is an avid collector of now-banned Jiang Zemin stickers.

Krish Raghav is a comic-book artist in Beijing. He was a punk, she did ballet. What more can he say?

Jaime (bot) works in Chaoyang and has moved to Chaoyang.

Yan Cong is a Beijing-based photographer, and one of the founders of Far & Near, a Substack about visual storytelling in China. You should subscribe!

Ting Lin is a writer in Beijing. She has very vivid nightmares about goldfish.

Yi-Ling Liu is a writer in Beijing. She believes deeply in the importance of spinal integrity & flexibility.

Diaodiao Yang is one of the co-hosts of Loud Murmurs, a Mandarin podcast about pop culture and more.

Simon Frank is a writer, editor, and musician in Beijing, and is unsure if he has described himself as a University of Toronto graduate before.

Henry Zhang is a writer in Beijing. He believes in life after love.