This dispatch appeared in S02 Episode 3, along with Flashing for Fun and Profit by Zoe Mou. The cover illustration is by Bo.

Krish: This is a story about wildly ambitious creativity in hardware.

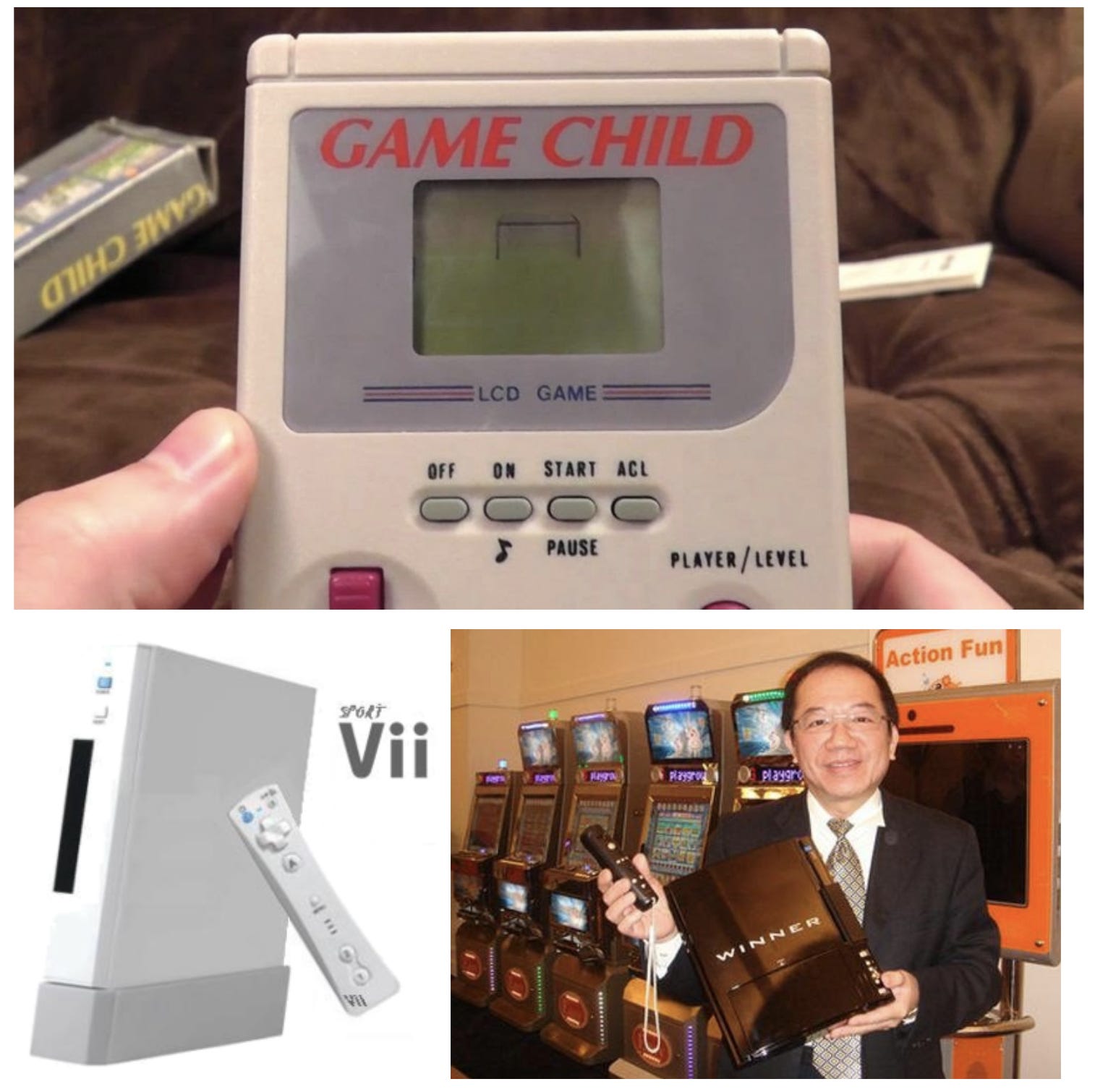

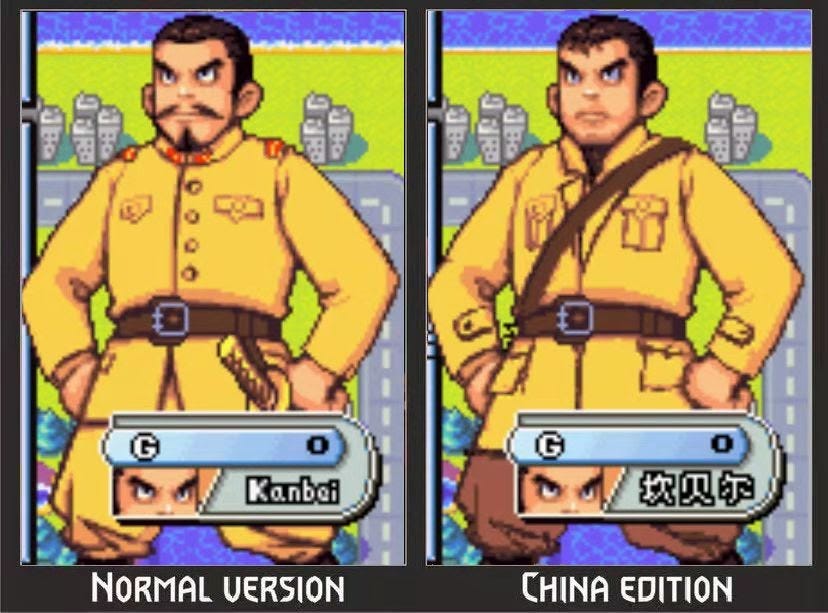

China banned foreign videogame consoles in 2000, but the ban didn’t stop console gaming. Not even a bit. It just redirected the energies of the industry to a madcap array of modified shanzhai devices, locally produced alternatives and mod-chipped knockoffs:

The sublime ideal of this era of hardware creativity appeared in 2003. This was the 神游机 or iQue Player (pronounced “I.Q”), a slightly insane officially-sanctioned Chinese variant of the Nintendo N64 console created to dodge the console ban, and allow Nintendo a path into the mainland market.

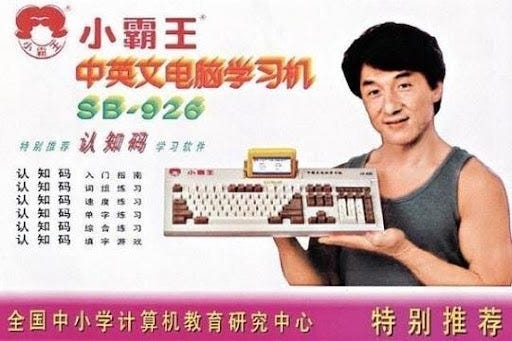

The iQue Player had big ideas. It had downloadable games and plans for a digital storefront before Steam even existed. Nintendo games at the time were consumed almost exclusively by proxy, through knock-off machines like the Subor “Famiclone” (小霸王), and the iQue promised a radical solution to the quirks of Chinese regulations, and China piracy.

Spoiler: it was a failure.

But its failure was consequential. There is a through line, in part, from iQue’s sunset and the eclipse of console gaming by PCs to the boom (and bust) in wangba internet cafes (网吧), the moral panics framing gaming as spiritual pollution, all the way to today’s curbs on game time and game licensing.

The iQue is worth remembering not just as a failed experiment but a big “what if” moment in China’s gaming history. To learn more, I interviewed @ChineseNintendo, a games archivist dedicated to building an online resource for iQue.

The story of Nintendo in China that we discuss isn’t just a nostalgic evocation of an already-known history. Parts of it prefigure what is happening in the Chinese games industry today.

Maybe it might even predict an unmapped future.

Krish: So, how would you like to be introduced?

ChineseNintendo: “He was not the first person to research iQue. He merely shared it with the western world, got over the language barrier, and helped build a worldwide community interested in a forgotten piece of gaming history in China.”

Krish: Perfect. So let’s start by setting that history in context. Because of China’s...unique experience with videogames, gamers here have a very different "timeline" of what games or systems are canonical. In a way, it upends traditional games history.

So, in the early 2000s, what was Nintendo’s position in the country? What games did gamers know, and were there any surprising differences between Nintendo's image in China and elsewhere?

CN: China’s gaming timeline is indeed different compared to that of developed nations, most notably for its fragmentation.

In terms of Nintendo, a large number of gamers moved from the GameBoy Advance to the PlayStation Portable, which surprisingly overshadowed the Nintendo DS in China in terms of popularity, and the abbreviation “PSP” was a synonym for handheld gaming devices until smartphones gained popularity in China. Many people didn’t know Super Mario Bros. (1986) was more than just the first Famicom title until they heard about Super Mario Odyssey (2017), missing out three decades of evolution in this world-famous franchise.

Krish: Can you talk about how iQue ended up becoming the representative of Nintendo in China? The central figure here is the founder Dr. Wei Yen (顏維群) who, before founding iQue, was an influential figure in the development of computer graphics.

CN: It may be loosely related to the 2000 console ban itself. The ban of all import videogames created a vacuum for a (legal) console gaming market in China, which could be easily circumvented by branding original designs as “domestic” consoles. Plus, most of the fear of videogames from Chinese parents and educators in the 1990s was probably targeted towards more “violent” or “explicit” arcade titles, which Dr. Yen saw as a path Nintendo games could avoid (at that time) for a more family-friendly experience.

Many articles written by Dr. Yen in the early years of iQue show his dream of educating children with the power of Nintendo games, specifically slogans like “Rouse potential and surpass the limits of intelligence” (激荡潜能 超越智慧), but it’s up to the reader’s jurisdiction how much that was a true wish and how much that was just marketing bluff.

However, the console ban affected more than legal import of gaming hardware, as it extended to the scrutiny of all gaming software and hardware being imported into China. Games took months to approve, which hampered iQue’s plan of releasing iQue Player games swiftly. Seminal titles like The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask were said to have been rejected for having “too dark” a theme.

Krish: The iQue Player fwiw is a bit of a hardware miracle. It’s basically the entire console compressed into a controller that just plugs into a TV. I’m exaggerating slightly here, but we wouldn’t see that kind of design in the mainstream until the Wii U decades later.

So could you talk about what made the iQue Player stand out, and what grand plans they had for it? In your mind, was it just a weird curiosity or did it leave any lasting impact on the gaming industry in China?

CN: In short, it was iQue’s redesign of the Nintendo 64, a brand new design to sell as domestic gaming hardware, and an all-digital distribution method to reduce costs of shipping and prevent piracy. It was later discovered by iQueBrew, a community of iQue Player homebrewers, that the iQue Player also possesses superior processing power compared to the N64.

iQue had great plans for the console’s digital storefront—iQue@Home, or 神游在线 (Literally: iQue Online) in Chinese. There were plans for online multiplayer, and an official forum for gaming fans, among others.

One could say Dr. Yen envisioned systems equivalent to, and predating, the Nintendo eShop, Nintendo Network, and Miiverse, or even Steam’s combination of storefront, community and multiplayer services. But it would be a bit of an exaggeration to say it kickstarted future digital distribution in China. iQue was a pioneer, but its grand ambition fell short due to both lack of player interest and technical limitations, so it did not make much of an impact. It was a forgotten grand plan.

iQue Player's packaging advertised that "Hundreds of Games" were to be "Coming Soon".

— Chinese Nintendo (@chinesenintendo) October 24, 2019

Only a total of 14 games were released througout the console's lifespan. pic.twitter.com/QGkilPCetU

Krish: You’ve archived a lot of their ads and promotional campaigns from that time, and there’s something refreshing about how…localized their marketing was.

CN: Much as I love iQue’s content under Dr. Yen with their autonomous and unique takes on advertising Nintendo IP in China (compared to Tencent’s more conservative approach today), I have to sadly admit that iQue in itself was a huge commercial failure. As such, it served as a warning to the executives of Nintendo how not to approach the Chinese market.

Krish: That sense only deepened with the failure of the iQue, and then, the failure of the Nintendo Wii in China. Can you talk about iQue’s “darkest year” of 2008?

CN: The failure to release the iQue Wii was probably the worst blow iQue had in the 2000s. With the Beijing Olympics on the horizon, it was a no-brainer to release the Wii into China. There was soaring interest in sports, not to mention the chance to put out a Beijing Olympics themed videogame featuring Mario.

If the iQue Wii had successfully made its entry into China alongside the Olympics, more people in the country would have learnt about the company, and through Mario & Sonic they would have gained a fresh new perspective on the red plumber they had previously only thought of as a pixelated character on the Famiclone.

But the Wii failed to get government approval. It was heavily believed that reforms within the government that year caused import game consoles to be scrutinized more strictly, and iQue wasn’t really able to pass off the iQue Wii as an “Interactive Multimedia System” like its handhelds. If the Wii played DVDs, would that have changed the course of history?

Krish: This led to iQue, and by extension Nintendo, pretty much retreating from China for a half-decade.

CN: iQue in the early 2000s worked closely with gaming magazines, communities and websites—doing events, giveaways, and other types of activities. But it was largely ignored in the Chinese gaming community as a whole.

I started reading Chinese gaming media in 2010, and boy, Nintendo did not have the most positive image. With iQue falling out of the spotlight and official Chinese support gradually dying out, it was obvious that fewer gamers and gaming media thought highly of the company.

Nintendo was often accused of sinophobia by disappointed gamers in the early to mid 2010s, and some infamous made-up articles mocking Nintendo were published during that time, one of which claimed Shigeru Miyamoto’s wife left home due to domestic violence.

I believe the abundance of Onion-level articles and focus on the negative side of Nintendo was something of a supply and demand relationship: The lack of Nintendo fans meant publishing articles against the company would not hamper their viewership.

Gaming media now paint Nintendo in a much more positive light, thanks to the popularity of the Nintendo Switch at home and the abundance of same-day Chinese language support. It was unimaginable for a Nintendo fan in 2015 that most future Nintendo games would have official Chinese translations, let alone available at launch. We have iQue to thank for that.

Yan: I found out recently that the iQue remains a really popular piece of hardware among speedrunners, because an unintentional consequence of the shortcuts and enhancements the device had to make in China is that it runs certain games (like The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time) without lag, making speedrun tricks easier to execute.

CN: You’re correct that iQue has a special relation to speedrunning since Chinese is a relatively concise language, which means faster text scrolling compared to other languages. Thus, many Ocarina of Time speedrunners tried their hands on the iQue Player version, and the world record for Super Mario Odyssey ran the game in Chinese text, translated by iQue.

Krish: Can you tell us more about games archiving in China, and how you got into it? I know of certain prominent general-purpose “retro gaming” Weibo accounts like Retro冷饭王, and there’s Chengdu’s 环球电子游戏文化博览馆 (Global Videogame Cultural Museum)—but where does iQue archiving reside online?

CN: My first iQue product was an iQue DS Lite purchased in 2009, but the iQue brand did not mean anything unique to me yet. Three years later, among the messy arguments on Baidu Tieba r/3DS over buying vs. pirating 3DS games and blaming Nintendo for neglecting Chinese speakers, I met OldBag and other iQue/Nintendo fans who gradually educated me on the history of Nintendo’s struggle in China, and that Nintendo’s current neglect was due to its past failures. These people later became the founding members of the QQ server “iQue Research Group.” Don’t try to ask for an invitation to the QQ chat or bother befriending OldBag though: iQue Research Group is more of a shitpost server today, and OldBag has retired from the frontlines of iQue Research and only dips his toes once in a while in the matter.

I don’t know much about the field of archiving in general. However, my datamining and research (if you can call my time crawling the Wayback Machine “research”) has contributed to the knowledgebase of gaming historians in China like @RetroDpad. There are many aspects of retro gaming in China (such as emulation, upscaling retro consoles, technical breakdowns etc.) which I am not well versed in, so I won’t say I’m part of the core of ‘game history’ yet, although I do consider myself something of a game historian on a specific subject.

I also have to thank my American friend and internet archivist DKL3 and my Canadian friend Bman, who reached out to me in 2017 in the interest of pursuing and archiving iQue content, and it was then that I realized a lot of the ideas we considered common knowledge were entirely unknown in the anglosphere.

The largest project in my plan is to make some kind of informal “documentary” on iQue and Nintendo, one not only showcasing hardware and software related to the company’s history, but also giving an in-depth discussion of the sociopolitical background at the time of release, as well as the technical caveats that make iQue products unique. I’ve had this idea for quite some time but had to put it on hold due...well, life.

Krish: Looking forward to that. Thanks so much, CN!

Krish is a comic book artist in Beijing who once made Flash games that no one will ever play.

Bo is a Shenzhen-based illustrator and animator. He believes in making life fun.

ChineseNintendo is on Twitter.

Yan Cong was born in Xicheng, grew up in Haidian, and is now based in Amsterdam, via New York and Chaoyang. She’s currently obsessed with the game Unpacking, which you cannot play on flash, but can play on Nintendo (Switch... and Steam).