In the house this week: Denni, Jaime, Lisha, Na, Yan, Krish, and Simon.

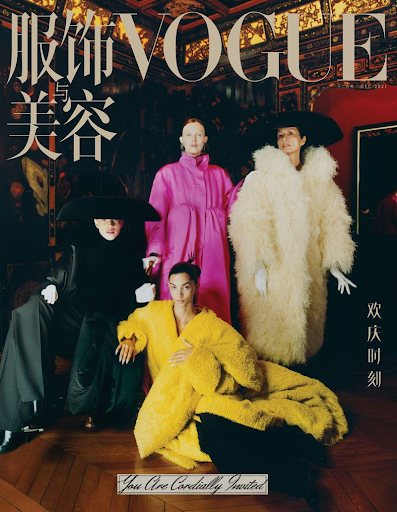

This dispatch appeared in S02 Episode 4, along with The Cloud in Sally Rooney's Room by Jaime. Cover illustration by Lisha Jiang.

Jaime: Hello friends. Our two stories this week are about creative agency (or the lack thereof), translation, and why people get mad about Ideas without looking at the structures in which they’re produced.

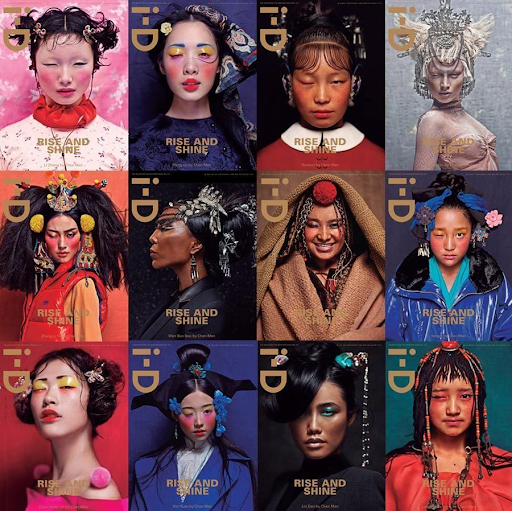

Last month, at the Art'n’Dior exhibition unveiled during Shanghai Art Week, photographer Chen Man's magazine work from nine years ago dredged up controversy and an onslaught of hate posts on Chinese social media.

Netizens and state media accused her of perpetuating Western stereotypes of the “Asian small eye” look in the “gloomy” portraits of Chinese women of minority ethnic groups, for which both she and the luxury brand apologized a week later. The photo was removed from the exhibition. The anti-intellectualism of this strain of nationalistic cancel culture aside, to what extent are fashion editors and artists responsible for decisions that are the results of more fundamentally problematic ways modern fashion media has been set up in China, especially in relation to the luxury and fashion industry?

Legacy print publications everywhere in the world are haunted by the failure of the advertising business model to adapt to the compromises between capital and editorial integrity, resulting in the common scenario where if the brand asks for certain editorial content from a title and the editorial team fails to comply, the sales team would apologize to the brand and offer to compensate with even more editorial content. Coupled with the burden of representation and struggle to shape and assert some form of “Chinese” identity through beauty and style on this misappropriated stage, no wonder everyone is mad, someone is always apologizing, and no one is having fun.

Who are fashion magazines even for anymore? What gets lost when media serves brands and advertisers rather than readers? Who will decolonize fashion magazines? (Not a 27-year-old Australian-Chinese fashion blogger.)

From one media industry worker and insider’s perspective, there are more frustrations and questions than solutions in what might be the first op-ed in Chaoyang Trap. We hope that this open letter of sorts will provide some context to how we think about the conflicting interests of globalized capital, beauty’s potential, representation, and creative agency. What if more money does not translate to more power for the individual?

What if capitalism sucks for everyone?

The Beautiful, Glossy Lies of China’s Fashion Magazines

Denni: China’s fashion magazines are not thriving.

They’ve ceded their power to brands and celebrities, and their sense of style is increasingly disconnected from reality.

Fashion and power are, of course, eternal topics in this industry defined by beauty and creative forces. Yet the rise of Chinese consumer power didn't help propel established Chinese fashion media forward—their insignificance only accelerated by the increasing demands of the brands that support them and an over-reliance on the advertisement business model after the internet’s disruption. Chinese fashion magazines have peddled a narrative of a westernized ideal of womanhood—the “fiction” of an independent woman who can become a western ideal through her purchasing power.

Only until the rise of China as a global power did magazines seek to catch up, stressing a need to express Chinese femininity and modernity. Yet, most portrayals, as in Chen Man’s case, tended to look at the Chinese woman as a symbol instead of a real person—a warrior-like figure, a guardian of Chinese heritage and culture. Coupled with blatant branded content, they created an easy target for online criticism. At the root of such misunderstandings was the clash between the westernization of the Chinese woman and real Chinese women.

Jaime: #weareallmulan

For fashion magazines, creative freedom is often not free but handicapped by the bottom line. Before the recent crackdown on celebrity culture, fashion publications had seemingly found a way to balance monetization and localization: the “ageless cuteness” of Chinese celebrities like Angelababy, Yang Mi, Xiao Zhan, and Jing Boran drove traffic and created immediate hype, which easily converted to magazine sales. An issue of Harper’s Bazaar e-magazine featuring Xiao Zhan and Wang Yibo sold over 1.26 million copies at 6 RMB per copy. You can see why magazines became so keen on chasing after celebrity culture, right up until the party came to an abrupt end.

But this is only one of the many paradoxes in the contemporary fashion media landscape.

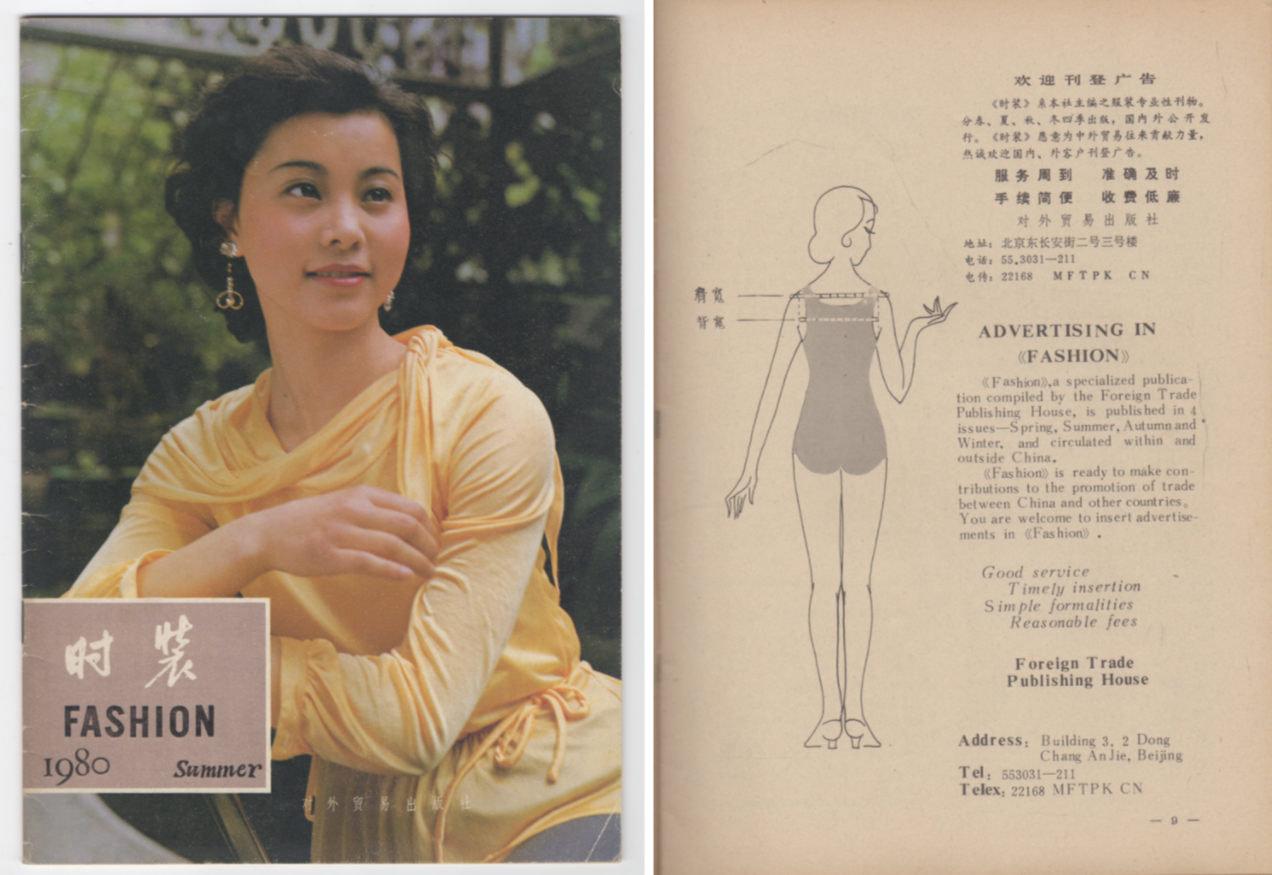

Short Colonial History of Chinese Fashion Magazines

The first modern day fashion magazine was《时装》(Fashion), founded in 1980 and coinciding with the era of Reform and Opening Up. Almost a decade later, Elle China became the first syndicated fashion title in China. In 1992, Louis Vuitton opened its first shop at Beijing’s Imperial Palace Hotel, followed by Hermès in 1997 and Chanel in 1999. Brands entering the market further propelled the growth of magazines, since they needed a local voice to spread their savoir-faire gospel. Harper's Bazaar, Elle China, and Vogue China soon became the holy trinity of fashion magazines in China in the aughts, whilst establishing the three Devils that Wear Prada—Angelica Cheung, Xiao Xue, and Su Mang—who almost collectively came from business, rather than editorial, backgrounds.

In theory, magazines could pick their own editor-in-chief, but technically they never had true editorial power since all magazines and their ISSN numbers were owned by the Chinese government. Local fashion glossies existed as syndications, with censors having final say on all editorial content. Homegrown publications such as iLOOK, launched in 1998 by culture personality Huang Hung and dubbed “a magazine for women with brains,” also garnered attention, but major fashion advertisers still favored Western glossies in general. 《明日风尚》(Ming), launched in 2007 by Hong Kong’s Ming Pao Weekly’s EIC Jessica Wong (黄宝玉), provided “a window, a mirror” to the global cosmopolitan class, but folded in 2015.

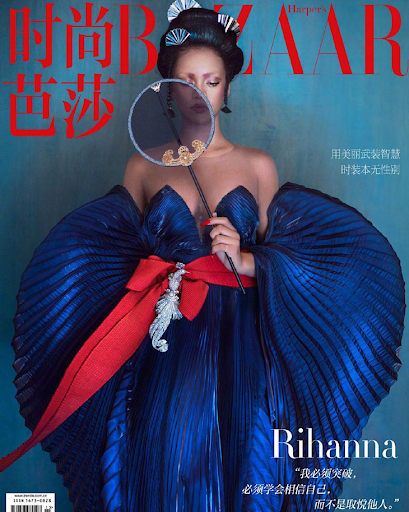

Magazines became a fashion education for many and saving up for the latest issue of Vogue was my monthly ritual. Before the internet, magazines could afford insane ideas with overflowing budgets. Often shot by globally renowned photographers like Mario Testino, Tim Walker, with international top models on the cover, these glossies provided joyous beauty and surprise: fashion was a key source of entertainment, fashion was “literature”, fashion was digestible art. It made 10-year-old me feel alive, and for a while, I was certain that becoming a magazine editor was my true calling. I still remember marveling at a 2008 Maggie Cheung cover, where she was covered in a badminton ball dress designed by Martin Margiela, to celebrate the Beijing Olympics. Other fashion magazines fought for prime spots on the newsstand, Modern Weekly's Fashion section introduced the avant-garde to the mass, Men's Uno emerged with its ratchet sexual energy, every other cover with Zhang Ziyi or Fan Bingbing would be an event in itself.

Yan: Denni’s personal story with fashion magazines resonates with me so much. When I was a 6th grader, I’d save up pocket money to buy 瑞丽 The Ray, a Japanese syndication, which had three different magazines (服饰美容,伊人风尚,可爱先锋) targeting young women of all age groups, from office white collars to teenagers. It sounds funny to say this now, but at the time it gave me the idea that my sense of self can be constructed by how I look—even though I could not afford any fashion items recommended by the magazines (and I had to wear school uniforms everyday).

The very act of reading them helped construct my identity, in a weird way.

There were also other Japanese syndicates such as 昕薇 (Vivi) and 米娜 (Mina) that were well-received in 2000s China. These catered more towards a so-called “East Asian aesthetic,” making them popular among Chinese readers. Maybe this was why I was drawn to them in the first place—being able to see someone who looked like me on the cover when I passed by newsstands. The Ray also cultivated a group of models who went on to become full-blown celebrities in China, like Yang Mi and Gao Yuanyuan.

Denni: Fast forward to 2020: The old guard that had crafted the fashion magazine landscape left the scene almost simultaneously. These ambitious women more or less found traditional media limiting and left at a time when ad sales numbers in the reds made exiting seem like a natural decision. (According to Statistica, annual magazine ad revenue is expected to drop almost 18% from 2020 to 2023.) They found their second life scattered across industries, be it investing, e-commerce (微商), or sustainability marketing. They also left behind a legacy and a mess.

Short Neo-colonial History of Chinese Fashion Magazines

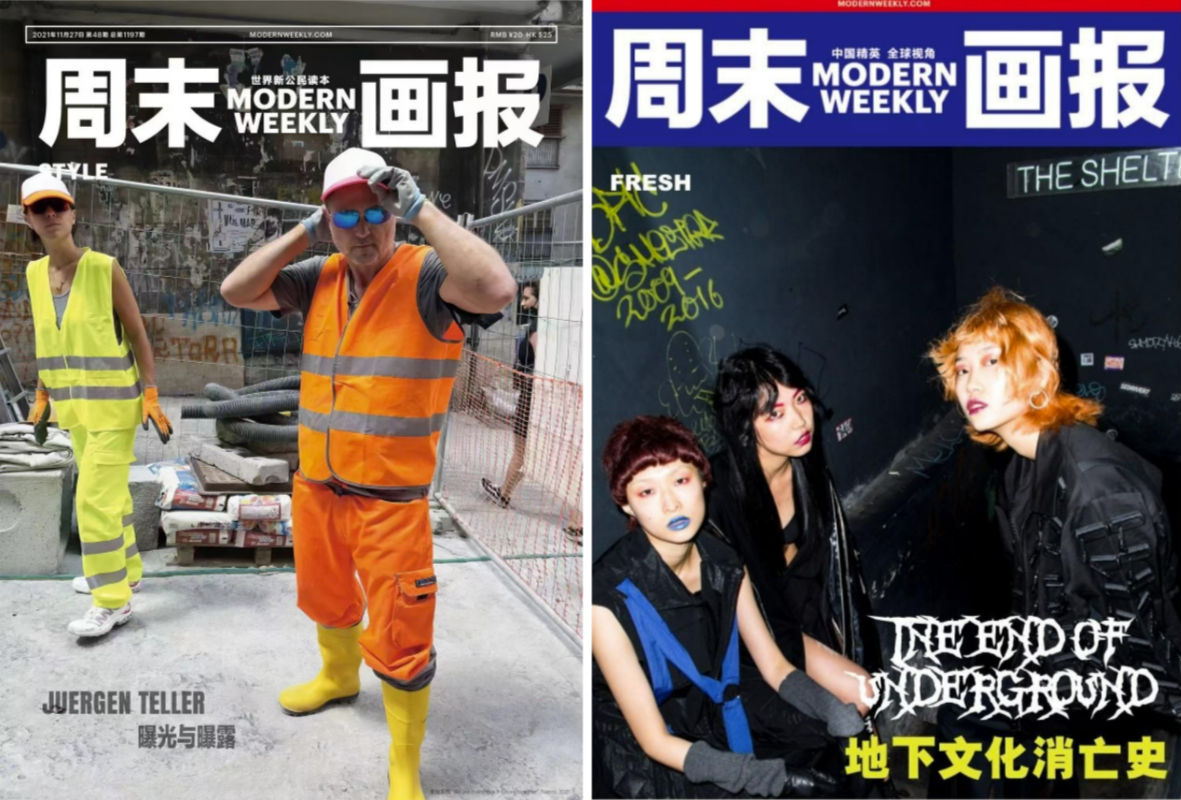

Quickly, new syndicated titles burst onto the scene. If the established fashion publications showed us what it's like to be rich and famous, the new media company Xuxu Huasheng (栩栩华生) saw a business opportunity to fill “niche” needs of both brands and audiences, built on the nuances of local cultures instead of in-your-face glitz and glamour. Backed by CMC Capital Group, the new Devil Wears Prada is Chuxuan Feng. He knew the market wanted something new, but Western brands were hard pressed to accept anything too new, so by buying up Chinese licensing rights to maturing niche publications like T Magazine, The New York Times Travel Magazine, Wallpaper, Nylon, and WSJ Magazine, he quickly gained acceptance (and ad money) from Western brands.

The Xuxu Huasheng business model was not that different from traditional fashion publications, but being new is certainly a virtue. T Magazine created a Chinese identity for the middle-class intellectual, whose thirst for sophistication and taste may be quenched by minimalist, moody editorials of celebrities like Li Jiaqi talking about their philosophy on life; niche young creatives, artists, and DJs belonging to the sorority of ya-subculture (the phenomenon of the lifestyle and consumption of subculture as subculture) also made their way into the magazine, signifying free spirit and alternative sass; models like Liu Wen and Ju Xiaowen often came aglazed by neo-Oriental filters, wearing Balenciaga or niche avant-garde fashion, performing Shang Chi-like feminist ideals as an otherworldly heroine.

While it might sound like a good thing that makes room for creativity (and jobs) when smart brands actually want their paid content to look editorial, the illusion of freedom just complicates the power struggle between capital and creativity. The progressiveness of Chinese fashion magazines might have appeared like a gesture of zeitgeisty know-how, but even with a more humanistic take on the message, it still fundamentally operates from a capitalistic point of view. They still cater to the same advertisers, producing what the brands deem high-brow and artsy. It doesn’t help that the same strategy also caters to monied local brands looking for an identity revamp, propelling a certain brand of westernization. Chineseness became a “style” and a moodboard.

The Paradox of Fashion Journalism in China

Markets and aesthetics may evolve, but the inherent issues that have overshadowed the industry from its very start remain unresolved. There's no true diversity, not enough real estate for editorial integrity, let alone freedom to create beauty that reflects how we live or what we aspire to—real culture creation. As a photographer friend once put it, the industry is so colonized that the only viable ideas are what sells to advertisers rather than how fashion reflects our reality, and so without being able to create fresh feelings and showing contemporary China through a fashion lens, all participants become complicit fashion victims of sorts.

What a time to be alive pic.twitter.com/es1qjrxXIn

— N95-masked RF Parsley (@sanverde) November 10, 2017

A colonized industry to begin with, efforts to explore a version of Chineseness for Chinese readers seems lacking from the media. In turn, this void has been filled by fashion boutiques, most notably Dongliang in Beijing and Labelhood in Shanghai. During Shanghai Fashion Week every six months, Labelhood showcases the best in class of emerging Chinese designers, and crowds from their constellation, fashion hipsters, and, most importantly, the ya sorority members all gather to cheer for them as they feel seen. A new class of internationally recognized brands such as Shushu/Tong, Samuel Guì Yang, and Rui all found their footing in fashion at Labelhood. What started as a small boutique has come to function as both a showcase and an incubator—some might even call it a community.

Dongliang focused more on promoting Chineseness on the sales side such as by opening stores for established Chinese brands like Uma Wang and partnering with Shenzhen Fashion Week to cultivate fashion in Shenzhen, which then elevates the city’s established commercial brands.

Can Millennials Save Fashion Magazines

More Seventeen than Vogue, the social media platform Xiaohongshu has filled the creativity gap for the younger generation by acting as a kind of magazine with endlessly diversifying content on endless scroll. Still, for some reason, an appetite for print culture has persisted. So it was not surprising that hope was pinned on the millennial Australian-Chinese blogger/stylist/general digital new generation person Margaret Zhang when, at age 27, she was announced to be the new (and youngest) editor-in-chief of Vogue China in early 2021.

All eyes were on her to create a fresh new look for a rusting empire, but the business side of things has proven to be too monstrous to let her roam free. Creative agency is now fully in the hands of the brand. When Chanel wants a Vogue cover story with a "total look" of the brand, there is little room for argument. And since the internet has broken down hierarchies and redistributed our attention span and focus even more—in short, became print’s mortal enemy—for fashion publications, that means short-term compromises became the norm. The bread and butter of legacy titles became branded content and paid events, and creativity became more hounded by annual revenue.

The most important storyline of who Chinese women are today gets buried when short-term market needs triumphs all. If the most vital and established medium for visual representation of the Chinese woman has been normalized to privilege Chineseness for capital and westernized needs, where can we find representation of Chinese women?

Since media and culture are already so decentralized and fractured to dust-sized niches, maybe it could be worth looking to local historical entities for salvation.

Let’s look to 《玲珑》(Ling Long) or 《新女性》(New Woman) in the early 1930s for a plausible outlook, both hyper-local publications aimed at documenting the lifestyle and livelihood of professional women during the Republic of China era—women with petit bourgeois tastes, who are smart and homely at the same time. They were not dissimilar to Elle magazine around the same era, when Barthes’ quip that their readers are entitled “only to fiction”, except the fiction in this reality could mean so much more than grooming omnipotent heroines who are perfect to a fault.

Hope in a Hopeless Place

These uncertain times are also hard on creatives working in fashion media and publications, when self-censorship is the norm. Those of us in the system see no way out. In the early and late 2000s, working at a fashion publication was like getting a masters degree at an Ivy League, and striking it out on your own afterwards means affluence and influence, but the powers have since shifted to social media and KOLs.

Many editors now see the influencer economy as a more promising career trajectory, but algorithms are a fickle thing, especially in China.

In these times, pandering to the needs of luxury brands can only result in symbiotic downfall, having to apologize like Chen Man when the party comes to an abrupt halt at any time. But some of us haven’t given up hope that an extreme form of creative collaboration with brands could bear fruit to something creatively substantial, even if it just takes time. Others seek creative agency in other mediums, perhaps even paying for their own shoots with their fashion media salary and celebrity styling gigs. Some started their own online publication like The Ballroom by Lucia Liu (T Magazine’s first executive deputy editor). But the new crop of fashion magazines are more like scattered words than a statement; they still lack the gravitas of a full-blown magazine, and substance that can provide footnotes to the history of fashion in China.

Ideally it will be the next generation of perhaps non-fashion elites to reestablish a system, who can also broaden the scope of advertisers and change the business model, and at the same time, make fashion editorial sharp, fun, dynamic, and in touch with the world again.

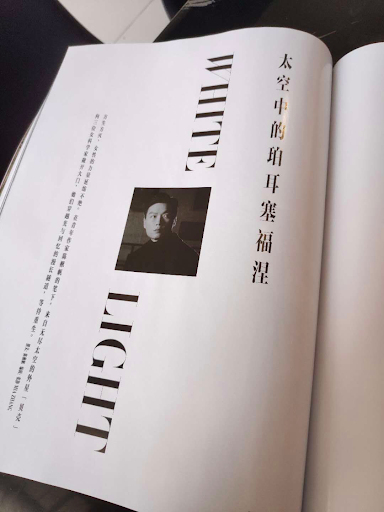

Yan: There’s this connection between men’s fashion magazines and nonfiction longform journalism that exists in both the U.S. and in China. I’m thinking of 60-70s “new journalism,” exemplified by Gay Talese’s “Frank Sinatra has a Cold” in Esquire, and the strong work produced by reporters at Esquire China and GQ China in the past few years—the most successful piece being Du Qiang’s 太平洋大逃杀亲历者自述 (“Massacre in the Pacific”), about a Chinese fishing expedition that devolves into a mutinous bloodbath.

What’s behind this connection seems to be a rationale that male readers are more sophisticated and care to read literary journalism, while women are simply treated as consumers. Am I wrong here? Maybe I’m not giving Teen Vogue enough credit for their dedication to quality journalism? But then, is there a Teen Vogue of China, and does China need one at all?

Jaime: What Yan said reminds me of this borderline misogynist spon-con风 short story by sci-fi wunderkind Chen Qiufan recently published in Vogue China (the same issue that features cyborg Gongli on the cover), which struck me as out of touch and cringe—it would’ve been more to the point if they published a story authored by AI. I refuse to believe that the commission is a real idea from a real magazine editor, but readers can be their own judge.

My medium-to-hot-take is I do think there is a case to be made where in a media environment as stifled as it is now, fashion and beauty should’ve remained as one of the more open channels for creativity. Maybe you can’t do nudity or make underwear out of flags and fashion is ultimately a material industry but in some ways superfluous frivolity makes the barrier of entry lower in terms of expression. Some Soviet fashion magazines seemed fine! But of course, keeping in mind that state capitalism has made things awkward when the instinct to defend one leaves the other compromised.

Simon: Having encountered the fashion industry/fashion media in China more peripherally than head-on—in terms of crossover collaborations with the art world, or fashion personalities that turn up at music scene events—it has always struck me as a curious mix of highly developed and rootless. On the one hand, it can produce designers, photographers (though not purely a fashion figure, Ren Hang comes to mind), and models that have found great international success. And yet, the mechanisms connecting high fashion to the fashions of daily life (even in a coastal, urban, middle-upper class milieu), seem totally opaque to me. Are the trends espoused by the media actually trends? Denni’s comment above about “ya-subculture” as something that would be explored by T-Magazine actually got me thinking that it’s slightly different from a received, literati-like aesthetic. Dressing “ya,” like a combination between a club kid, a nu-metal fan circa 1999, and a Shibuya-kei star actually appears to have a grassroots precedent from the shamate subculture of the early 2000s. Though I’m pretty far from this world, it seems to me that it might organically seem cool to Beijing high schooler in 2021?

All that being said, I’m kind of jealous that the fashion world has a media ecosystem left to critique, which can barely be said about other creative fields in China these days.

Also, I’d like to sum up my thoughts on fashion in China with a meme:

Denni is a fashion editor and aspiring podcaster based in Shanghai.

Jaime is an editor who lives and works in Chaoyang.

Lisha Jiang is an illustrator and comic artist in Hangzhou. She collects comic books, plastic toys, and anything glittery. She is generally considered a fashion disaster.

Yan Cong was born in Xicheng, grew up in Haidian, and is now based in Amsterdam, via New York and Chaoyang. She writes for another Substack Far & Near on visual storytelling in China. You should subscribe!

Simon Frank is a writer, translator, and musician in Beijing. He hopes that Christopher Lemaire might one day hear his music.