In the house this week: Henry, Light, Yi-Ling, Zoe, Simon, Krish, Aaron, Jaime, Yan, and Tianyu, but which one of us is the killer?

Krish: Hello, we’d like to report some murders.

Welcome to Episode 5. You might be surprised to see us covering Jubensha now.

China’s murder mystery escape room werewolf LARPs were top of the trend charts in 2021. They’re already the third biggest form of offline entertainment behind films and sport. Pandemic prevention notices mention them specifically whenever there’s an outbreak. The New York Times has written about them.

But now that they’ve moved from the peak of inflated expectations (i.e. a fengkou) to the plateau of managing Dianping ratings, it’s time to look at the medium’s formal properties.

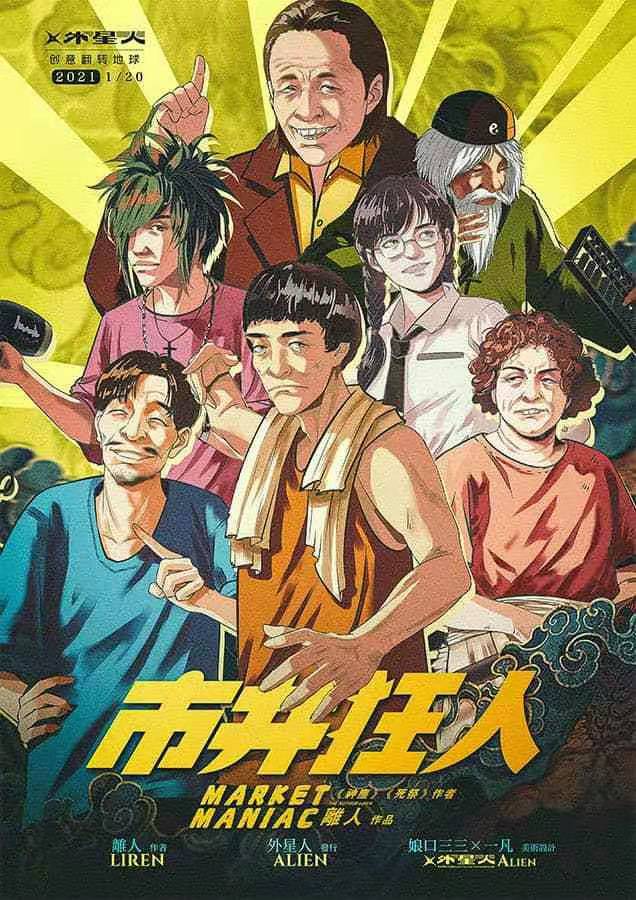

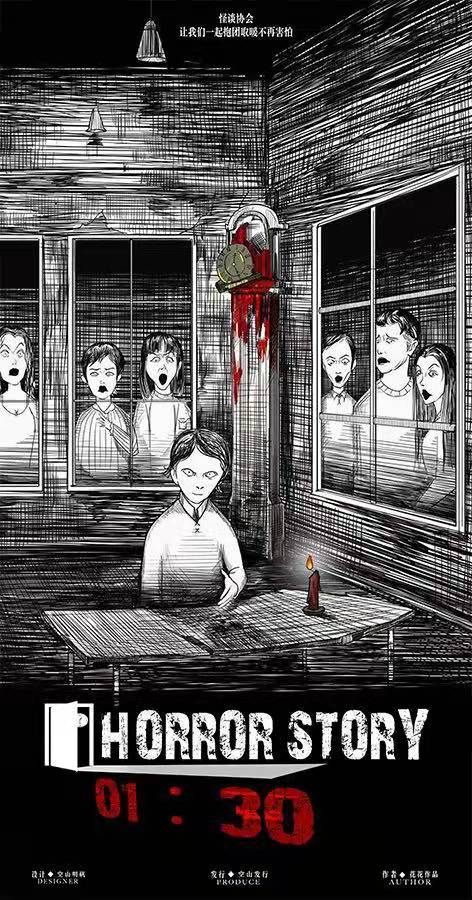

For one, intertextuality of kaleidoscopic dimensions is the lifeblood of the Jubensha scene. Scripts and scenarios in the scene are wild with citation, pastiche, imitation and “heavy” “inspiration,” drawing from video games, c-dramas, horror, sci-fi, revolutionary history, internet novels, and fan-fiction. These crash into a decade of obsession with escape rooms and immersive theater (Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More is still sold out every night in Shanghai), making the medium both thematically and mechanically worth examining.

In 2022’s first Chaoyang Trap, Henry threads the pins on the cork board to solve the Jubensha mystery. How did a curious mix of subgenres morph into a privileged Chinese medium “on par with bar-hopping or moviegoing?”

On Jubensha

By Henry Zhang

Henry: “No hookups; yes Jubensha”: this strange sentence abounds on China’s Tinder profiles—and unlike dubious declarations of penta-lingualism or offensive sub-saharan selfies, the enthusiasm that the country’s millennials and zoomers express for the medium seems genuine.

What is Jubensha? It’s the Sinicization of an early-20th-century American game, the Murder Mystery Party, which consists of an impromptu and imperfect homicide trial for which players act as both jury and accused. Impromptu, since the actual institutional powers that be are often too distant or incompetent to reach the crime scene, giving deliberations an element of vigilante justice—and imperfect because each player harbors their own motives for wanting the victim dead. If there were a Jubensha made about Chaoyang Trap, for example, and I were the deceased, I might’ve tried to sell the platform to a venture capitalist or plagiarized from another member’s piece—enough to get you all fantasizing about my convenient exit from the scene.

This might sound like interesting but hopelessly dorky marginalia (which I’d still love!)—just think about the pejorative English word LARP—but in China, Jubensha has quickly become the “third most popular form of offline entertainment, behind movies and sports.”

In our 2nd episode, Ting noted the phenomenon by which a Western medium shrinks into a Chinese genre, as the monopoly of HBO or Netflix falters, in its transnational journey, to become one more Euro-American import, on par with jazz dance or pilates. With Jubensha, we are witnessing the reverse: an expansion of a largely-forgotten American subgenre into a privileged Chinese medium for social interaction, on par with barhopping or moviegoing.

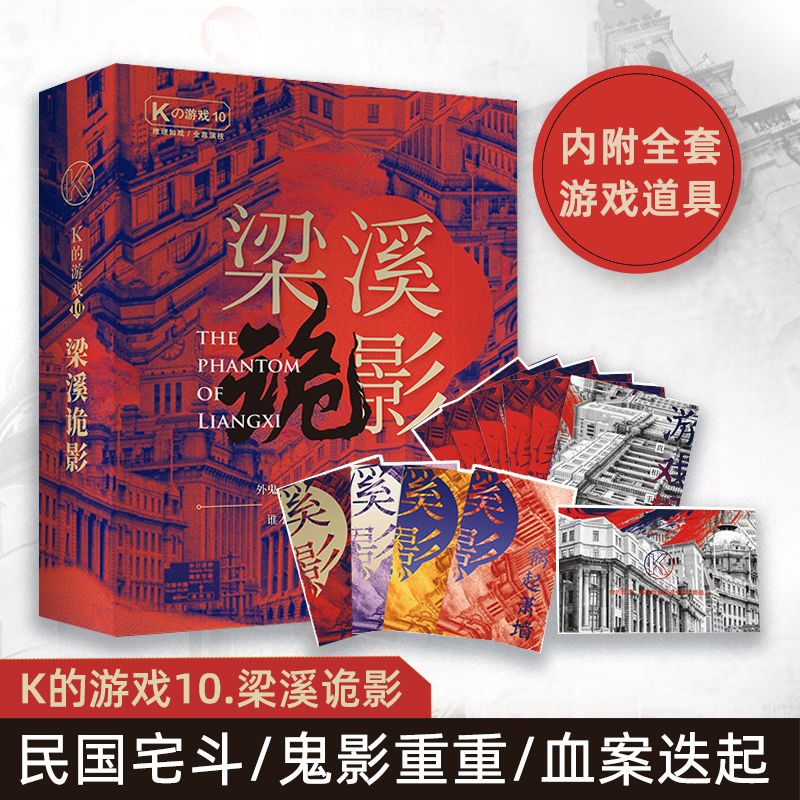

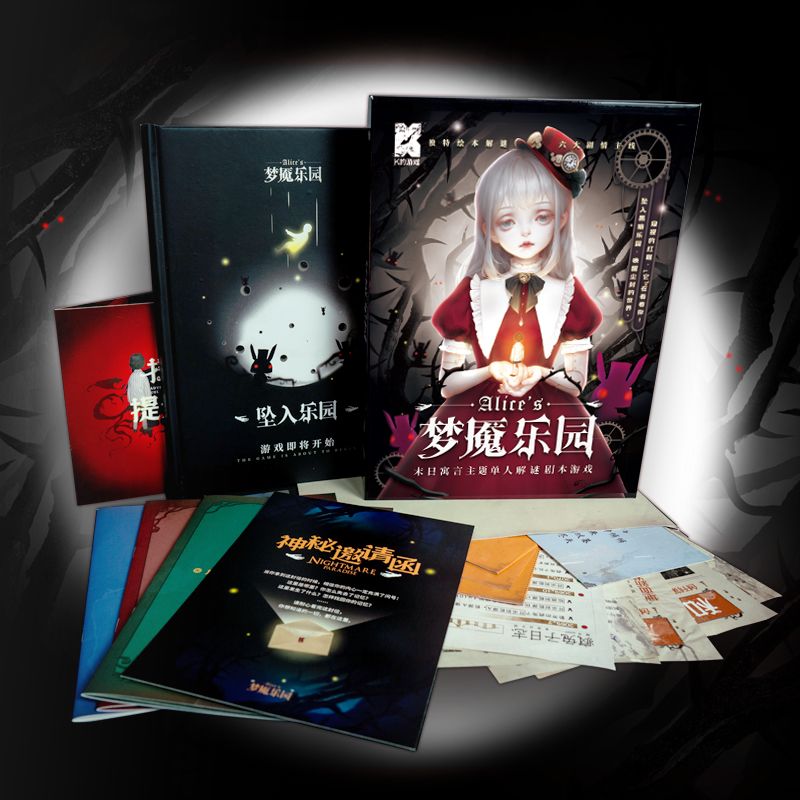

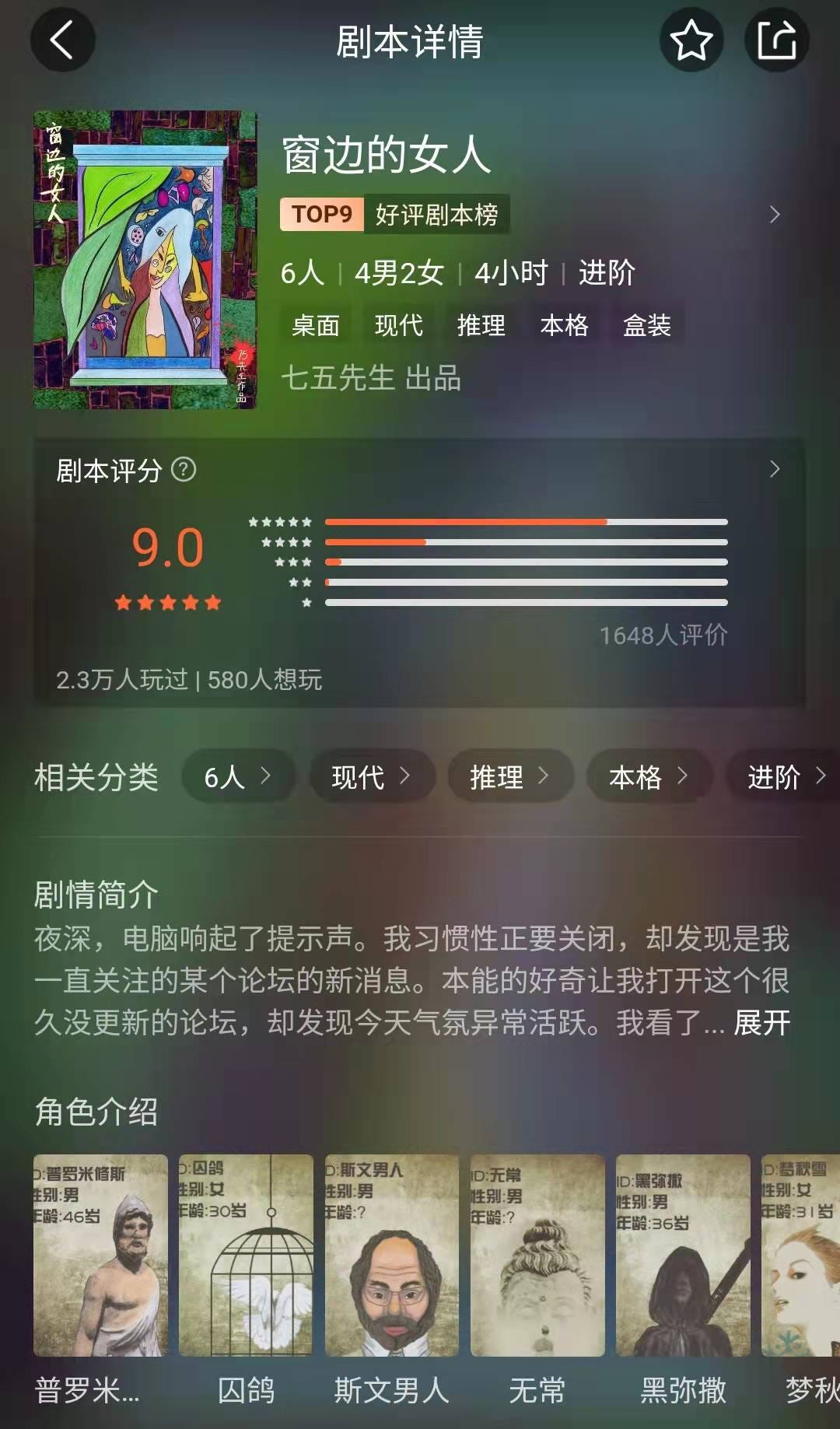

Jubensha entered the popular consciousness through a 2016 show, Who’s the Murderer (明星大侦探), was was intended capture part of the market share for previous crazes like Escape Room and Werewolf Game(狼人杀). It had to wait until the post-Covid world to find true popularity, going from about 7000 brick-and-mortar venues across the country last year to over 30,000 this summer. The variety of settings in which Jubensha happens, and the differences in players’ social backgrounds, attest to its penetration into Chinese life: there’s a live-action version, popular with a growing class of young professionals willing to pay premiums for set design and drinks; a couch-friendly board game version, which budget-conscious creatives can buy used, then resell on Xianyu; and finally, mobile apps, like I’m A Mystery (我是谜), which cater to the compulsorily transient and or the internationally mobile—out-of-province youths in first-tier cities or affluent students studying abroad.

Yi-Ling: One thing I was struck by was cost and how much it seemed like yuppies were willing to shell out for a Jubensha session, way outside of their typical spending capacity. (And a good portion on drinks–one Jubensha I participated in was insanely boozed-up.) I'm wondering what people feel like they are paying for–the novelty of the experience? The creativity of the script?

Henry: My first round of Jubensha took place in one of Beijing’s air-raid shelters, of which there are thousands, built in case of nuclear war (not just with the US, but the USSR). In stark contrast to the dingy staircase and dark corridor we passed through, the actual store—announced by a metal sign of Sherlock Holmes in profile—was newly-furnished and brightly-lit. On the ground, yellow tape delineated the crime scene: a set of rooms in medieval European style, in which we got on our knees to fish for murder implements beneath beds, or stepped on chairs to reach for suspicious letters above tall drawers. Afterwards, we retreated to a conference area, to reconstruct the crime, pin clues to people, and think up alibis—even if you aren’t the murderer, remember, you probably wanted the dead person dead.

The title of our scenario was “The Valentine Estate,” whose duke is the victim in question. (I haven’t been able to find the description online, because brick-and-mortar joints often buy up the exclusive rights to certain scripts, or write proprietary ones). I played the duke’s son, the heir presumptive; after getting into my frilly, epauletted costume, I read the script and discovered that, though I hadn’t killed my father, I had found his body, and, in a fit of despair and selfishness, stolen his seal ring to authorize a large transfer of money to my creditors. The young scion was a gambling addict, and if the others discovered his secret, I would lose my chance of victory.

Ultimately, the script’s lack of historical texture—Valentine feels vaguely Roman, but where, and when, were we, exactly?—detracted from the experience, but it was enough to get me hooked. I pleaded with my friends to play more Jubensha. Wanting to save money, we sprung for several of the board-game scenarios. You might be tempted to compare my journey from live-action to couch-co-op Jubensha with an addict’s transition from bordeaux to franzia, but in fact, couch co-op must compensate for its immateriality—a lack of set and stage—with great worldbuilding.

Henry: My favorite was Pagoda of Madness (疯人塔), a historical melodrama involving a sinister secret society, formed in the Zhou Dynasty, that is bent on infiltrating royal families across the ages, and the counter-society formed to hunt it down. Agents from both have appeared at the pagoda—a kind of ancient sanitarium—whose monk-physician has been killed, mysteriously, in a room that was locked from inside. Disfigured beauties, blind scholar-students, knights errant gather in the tower to dispense rough justice. I loved the lore: real, traditional Chinese potions, like mafeisan, act as poisons; victims are pronounced dead by checking their nostrils for breath; and a script written in quasi-classical Chinese.

The expansive, nearly operatic scale and tone deepened our desires to intrigue and plot. I watched, transfixed, as my friends, a couple both IRL and in-game, began to bicker over whether one was really the woman she claimed to be: after all, her face was unrecognizable after an accident involving acid—could he really trust her? Nostrils flared, she berated him for his conjugal skepticism—only to laugh, after he refrained from accusing her during the finale, at how stupid he’d been: she’d been an imposter after all.

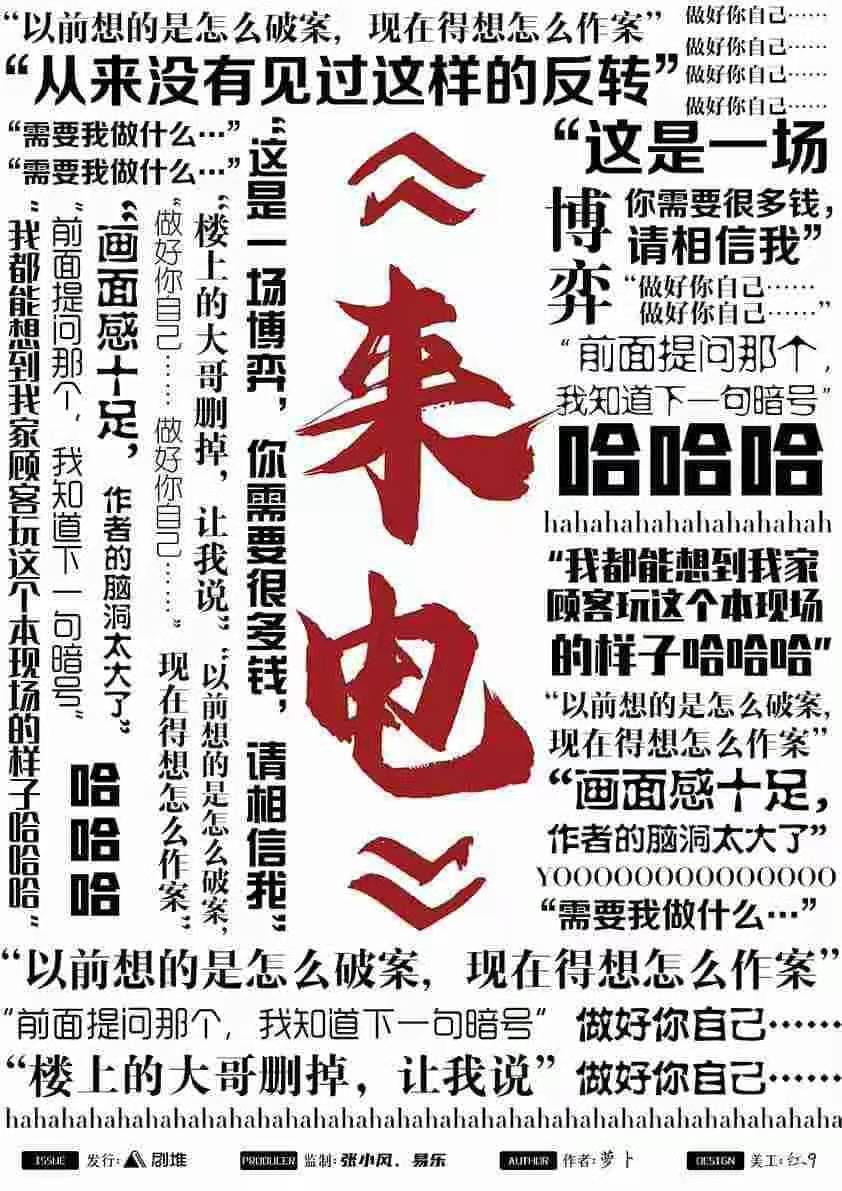

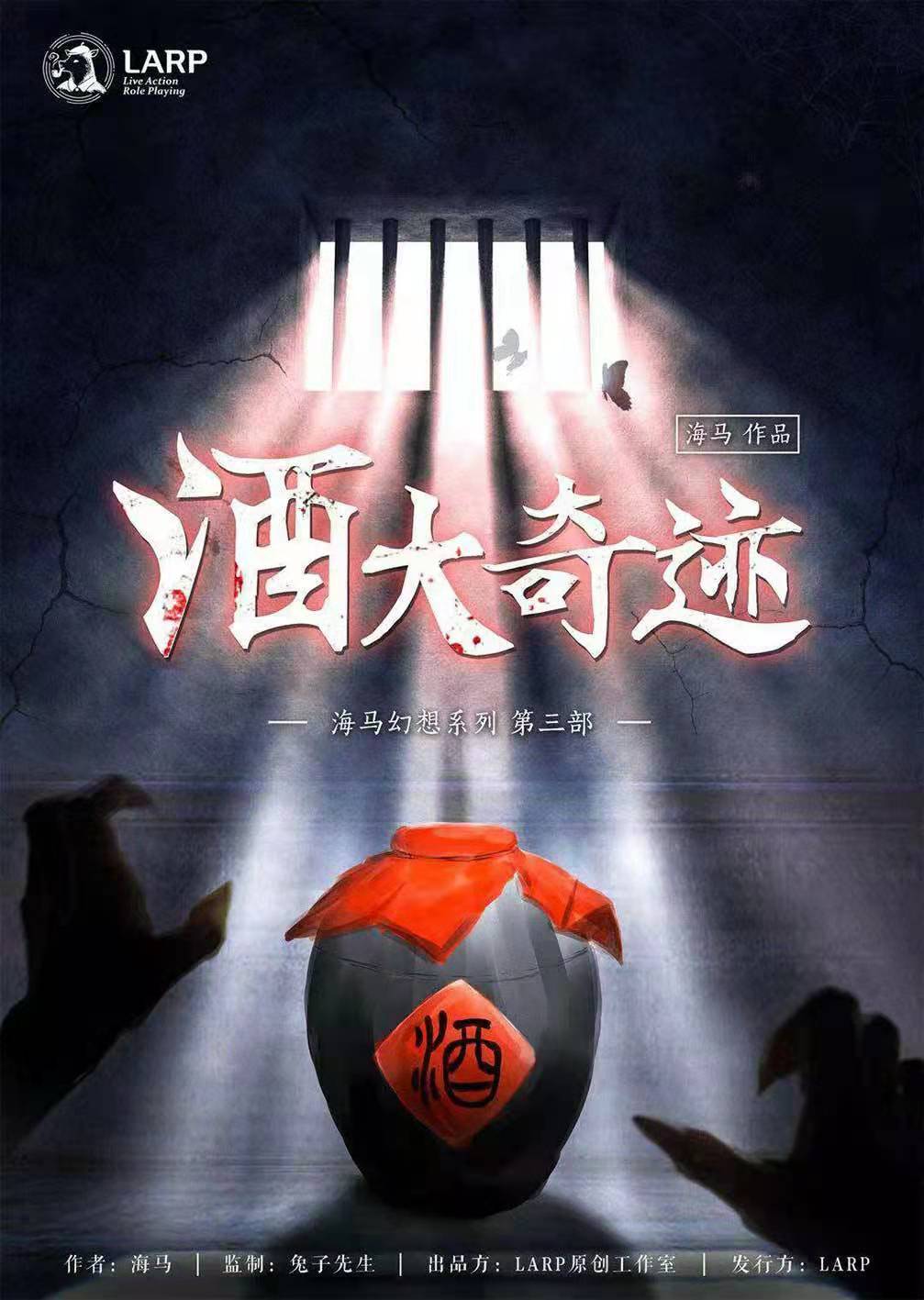

Quality, of course, comes at a price. Jubensha’s rapid expansion is causing growing pains: involution, as increased competition and readerly demand have sunk many operations; censorship, as the government denounces the game’s “bloody and gruesome” content; and finally, the risk of a vigorous, but short lifespan—that this is the hottest thing around doesn’t mean it’s not liable to cool down faster than you can say, China speed (cf. Simon Frank, episode six, on accelerationism’s discontents). Gone are Jubensha’s early, DIY days when shops were opened and scripts written by loving amateurs, for whom turning profits was an afterthought. The industry now draws underemployed movie and TV writers (who oftentimes have far more autonomy writing murder scripts than they would in their real jobs); and studios are Taylorizing game production: one writer develops the structure, another fills in the details, and yet another polishes the style.

Zoe: I should have seen this coming, but there are already patriotism-themed Jubensha. It’s interesting how Jubensha’s “live” and “improvised” nature resists the usual modes of censorship that the authorities might employ on film and broadcast media. If anything, what’s been most successful in tempering enthusiasm for Jubensha is pointing out that it’s pandemic-unfriendly. Big Brother might find it harder to stay on track with what’s happening in this medium.

Jaime: As someone who thinks going to her office job everyday is Jubensha enough already and thus remains an indifferent but open convert, Jubensha’s popularity seems theoretically most obvious as an event that embraces “the live” without fetishizing it and resists censorship through spontaneity like Zoe said (although I’m not sure if people consciously write or go into these games thinking, hehe they can’t stop me from what I’m about to say or do). Immersive theater like Sleep No More has been around for Chinese yuppies for a while and Jubensha also seems like a logical democratization of that—which makes me wonder if there are evil tech ways to monetize this aka what kind of data can be harvested and exploited from these activities? Or is Jubensha radical because it completely resists that?

Henry: How long will Jubensha’s career be? It all depends on how well it exceeds its generic conventions—a dead person and a hung jury—and on how many smart writers are drawn to it as a real art form. Maybe this is asking too much. As for Jubensha’s diaspora, I’ve participated first-hand—the friends who got me into Jubensha routinely schedule late-night video calls with peers in pajamas, in California, New York, Melbourne. After leaving Chaoyang, and the country, I downloaded a Jubensha mobile app, I Am A Mystery (我是迷). Technological ineptitude led me to accidentally click into a Kuaishou-style chatroom, where users belted the lyrics, Karaoke style, to corny Mainland rock songs, in between complaining about their lousy service jobs. Lying on a friend’s couch, in New York City, I wondered what it was they got from this app, from Jubensha in general.

Might it have to do with the medium’s allowance for bad endings? Frederic Jameson, contra Adorno, has defended Hollywood films for giving play to—though ultimately neutralizing—the public’s utopian impulses. The kernel of truth is there, couched in false directives. But so many big budget Chinese crime films—from Diao Yinan’s The Wild Goose Lake to Zeng Guoxiang’s Better Days—fail even this kind of ideological management. Call this a piggy ex machina: it’s hardly a thriller when the cops always win.

In both the Valentine estate and the pagoda of madness, the real murderer got away—and it was our fault. But there was something exciting in shouting that we’d known it all along, in portioning out the blame and responsibility for this miscarriage of justice. Much more satisfying to study from your failures than to claim a bogus victory.

Tianyu: After moving to the San Francisco Bay Area, I've seen quite a few local WeChat articles recommending Jubensha game rooms, few of which had a proper Google Maps or Yelp listing beyond an address and a GPS pin. Intuitively, this was reasonable—if the targeted customers are all Chinese, why bother explaining it in another language? I’ve also seen friends visiting escape rooms in major U.S. cities that cater to Chinese audiences (they are also everywhere on Xiaohongshu); it’s fascinating to see how Chinese games that recently became popular now find themselves in diaspora communities.

While the history of Chinese jubensha ultimately traces back to murder mystery games in the U.S. (see the Savannah murder mystery in The Office), and that there are murder mystery party rooms in America, I don’t think many of my friends that are into jubensha in China notice the connection! Maybe there aren’t a lot of similarities between the two versions. I have yet to play either, but please email me (tianyu AT chaoya.ng) if you’re in the Bay Area and want to try it out.

Simon: My main thought after discussing Jubensha in-depth for the first time with some friends was really that it filled a gap provided by the shortcomings of other media in China. If a horror film that actually gave you some psychological shocks could make its way to big screens, or if a more piquant video game could spread outside of Steam, would there really be such a need for this new format? Also, I think the activity says something about how the way people socialize and participate in leisure activities in China may be more “organized” than elsewhere. With a full awareness that what I think is “normal” is shaped by my class/cultural background, and perhaps personality, I feel like one is more likely to just casually hang out with North American friends, whereas in China, except perhaps with your closest friends, there needs to a plan: at least a dinner, or a KTV session, a tour, a class... To me, Henry stumbling upon users complaining about their jobs within I’m A Mystery encapsulates how people use these activities as a “frame” in which to create moments of vulnerability and bonding. Of course, people’s hobbies function like this anywhere in the world, but it is interesting that Jubensha harks back to party games from a time of relative scarcity in America, when you had to make your own entertainment, and someone had to sing or play an instrument if you wanted to hear music. After all, today we just need to touch a screen to be amused.

Curious if anyone knows of any anthropological or sociological work that touches upon these different ways of “hanging out.” Or am I just bad at making friends and plans? 😊

Krish: With the caveats that this research is a) from the early 2010s and b) primarily about an earlier stage of Chinese social media, I think Tricia Wang’s conception of the “elastic self” hints at some answers:

“Under semi-anonymous, [informal] conditions, Chinese youth are able to overcome the low levels of trust that characterize authoritarian societies and adopt broader forms of social trust that characterize more participatory societies…[they] are primarily seeking to discover their own social world and to create emotional connections—not grand political change.”

Again, recognizing that sometimes a LARP murder mystery is just a LARP murder mystery, maybe Jubensha (and its attendant apps) provide a frame for these exploratory “semi-anonymous” spaces today, allowing what Tricia calls the “trying on of heterodox identities” without shame or anxiety.

Yan: Maybe this also explains what I always think of as the unthinkable: people playing Jubensha with strangers. I’ve seen on Dianping where Jubensha studios sell individual tickets, and I always wonder if someone would just drop in and spontaneously start playing with whoever happens to be available. Maybe not knowing the people you play with makes it easier for you to immerse yourself in your role and in the story. It’s another layer of anonymity on top of the “semi-anonymous” space provided by Jubensha’s worldbuilding.

Krish: Yes! Tricia’s work, too, talks specifically about socializing with strangers as the hallmark of the elastic self.

Aaron: To me, it seems like Jubensha are filling a Dungeons & Dragons-sized hole in Chinese social life. Working in video games in China, it was interesting for me how few of my Chinese coworkers played D&D, even as they were often on top of the latest American or European video games and TV shows. But Jubensha provide a platform for a lot of the same aspects that have helped D&D keep rising in popularity in the US, allowing people to try on new identities and play collaboratively without needing any mediating devices.

Krish: Outro music this week is newish Beijing duo Naja Naja. They make warm, Moon Duo-adjacent minimal post punk, and just toured with newsletter faves Howie Lee and Hualun.

Here’s ‘Dong Dong’ from their debut EP, released on Bie Music on 24 December 2021. This has been 代购ed from the Chinese web with permission. An international release is scheduled for April 2022 via Wharf Cat Records.

Tianyu: That’s it for this episode! Next up: Rewilding.

Krish: Bye!

Henry Zhang doesn’t fall in love; he just plays Jubensha.

Light is a multimedia illustrator and designer based in Los Angeles.

Tianyu Fang is an intern.

Zoe has moved to Guizhou.

Yi-Ling Liu is a writer in Beijing.

Jaime Chu plays office Jubensha for rent in Chaoyang.

Krish Raghav is a comic artist in Beijing who would kill for some good dosa.

Yan Cong was born in Xicheng, grew up in Haidian, and is now based in Amsterdam, via New York and Chaoyang. She writes for another Substack Far & Near on visual storytelling in China. You should subscribe!

Simon Frank lives in Beijing and wonders if “the music scene” is live-action roleplay.

Aaron Fox-Lerner is a writer in New York.