In the house this week: Yi-Ling, Tianyu, Simon, Krish, and Yan.

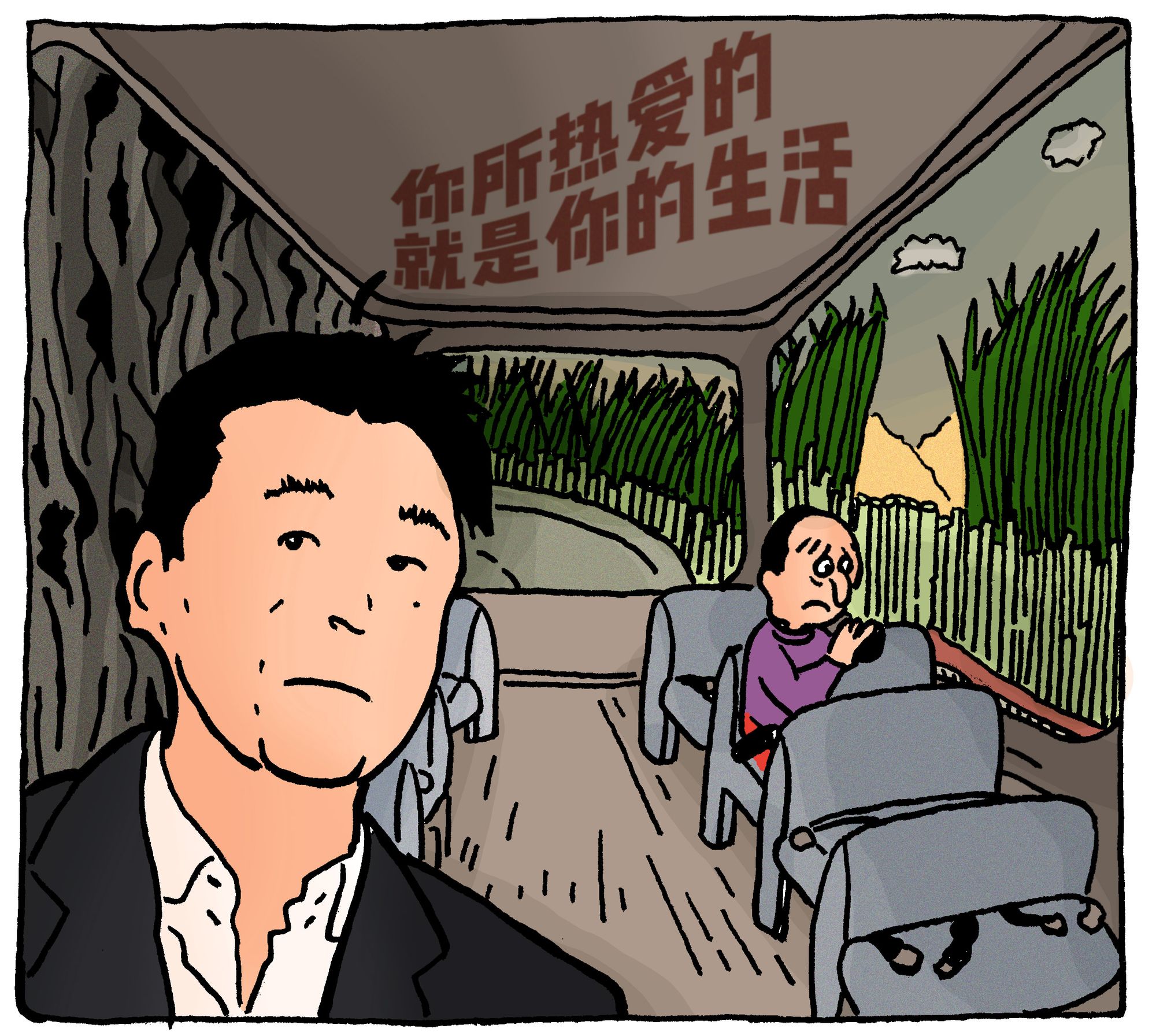

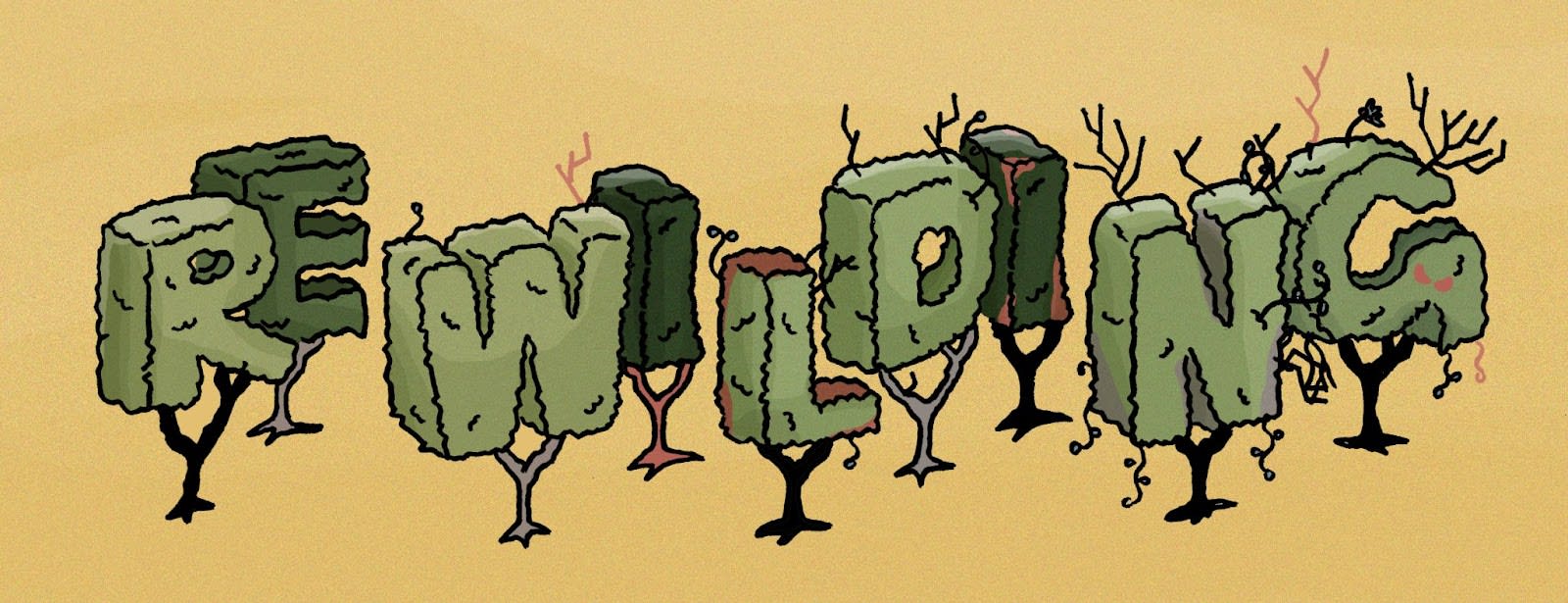

Yi-Ling: Rewilding is an exploration into the language of the Chinese internet.

In each issue, I pick a word from the labyrinthine swamp of online life in China, lay it on the table, scrutinize it and take it apart in the form of a mini-essay, then replant the pieces, sowing seeds for further conversation.

This week: the waves.

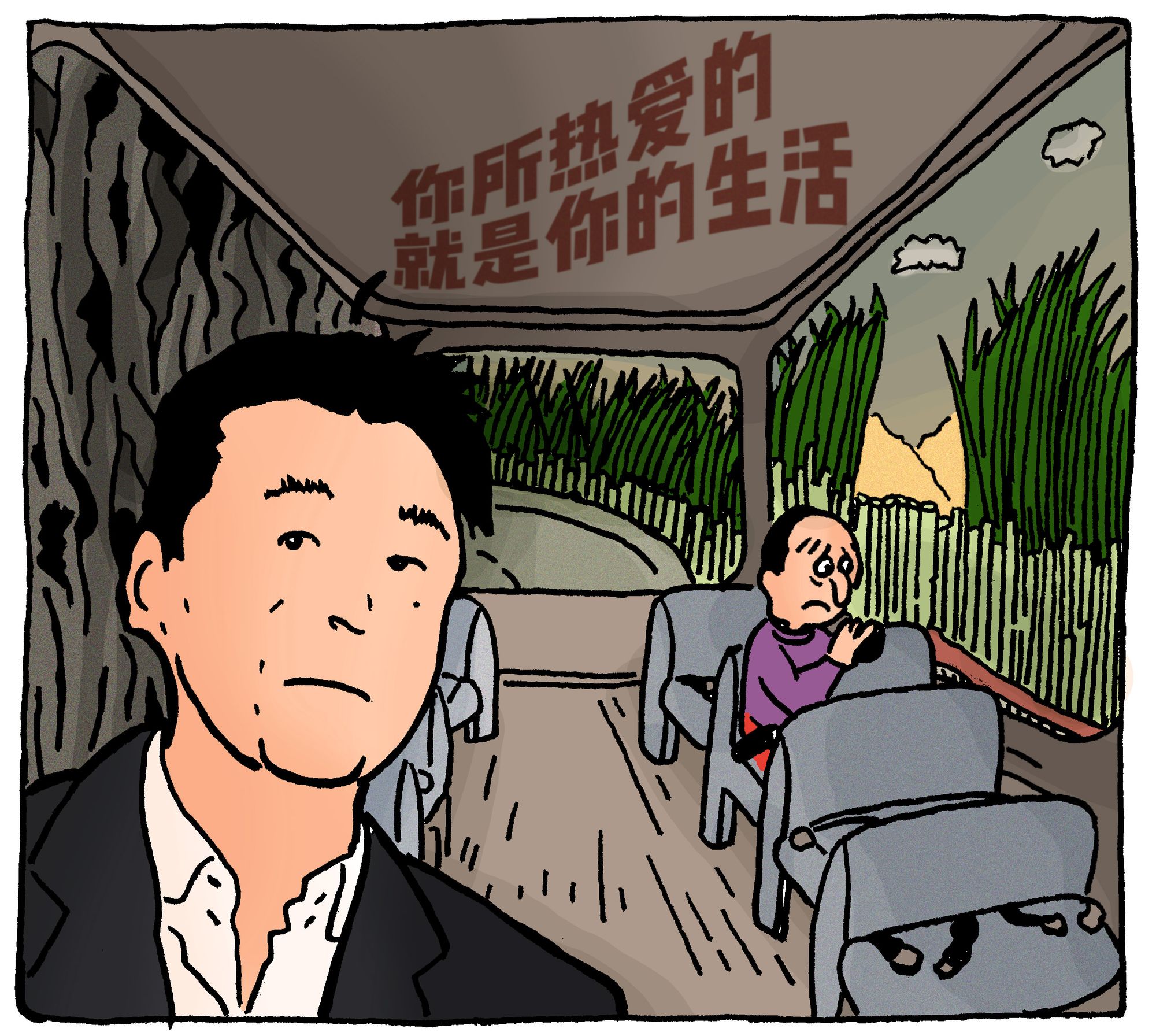

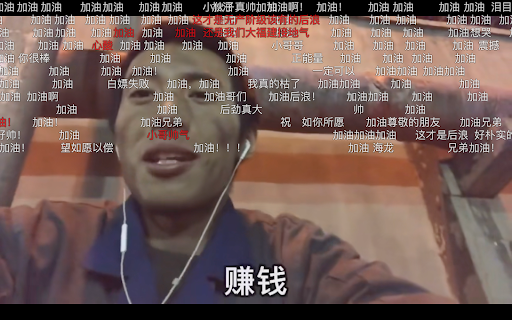

In May 2020, to celebrate China’s Youth Day, Bilibili released a video called “Rear Waves, Speech for a New Generation.” Opening with a dramatic montage—an astronaut landing and a glorious sunrise over a snow-flecked mountaintop—the video unfolds into a three-minute reel of Chinese twenty-somethings doing exciting things. It is a visual orgy of Positive Energy. They are hot, young and confident. They dance in hanfu, play Chinese instruments, try out VR glasses, practice calligraphy, skydive, scuba-dive, lift weights, and pose in front of the Eiffel Tower. “I look at you filled with envy,” says celebrity actor He Bing, who narrates the video in a paternalistic, sonorous tenor, filled with what netizens called diewei or “daddy vibes.” “A nation’s most beautiful scenery is its youth. Kind, brave, selfless, fearless…Surge ahead, rear waves!”

The video went viral—amassing more than 6 million views, airing on CCTV—thrust into the national limelight, alongside the phrase “rear waves.” To those who loved it, both the video and the term “rear waves" (后浪), which comes from the proverb “as the rear waves of the Yangtze River drive on the waves in front, so the new replaces the old,” captured the sense of pride and confidence that many Chinese youth feel, or at least some imagine that many feel, living in today’s China. Reaping the riches sowed by their predecessors, they are wealthier, more powerful and more patriotic than ever before.

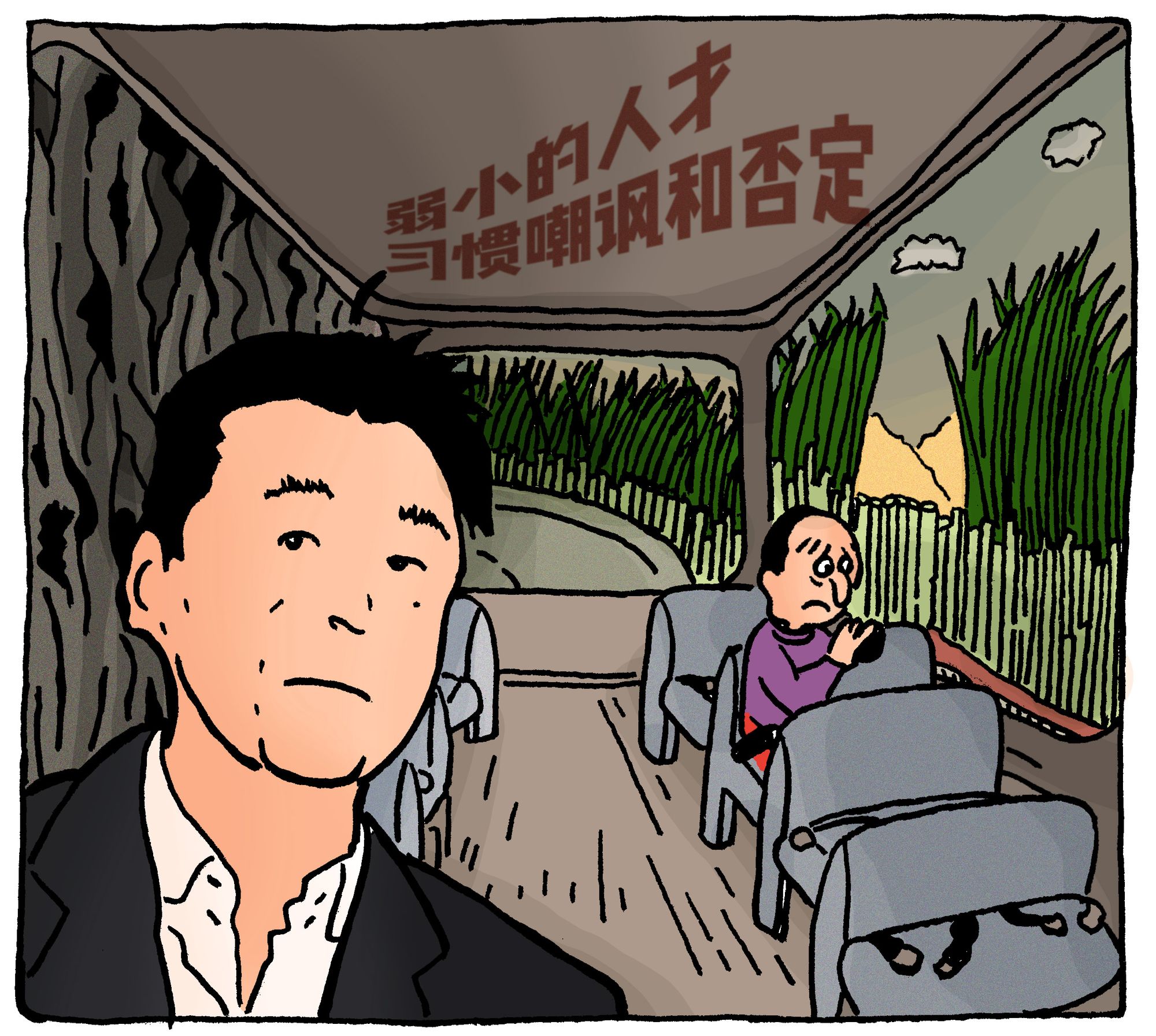

But many more responded to the video with cynicism, riffing on the image of the wave. “Young people have to change their lyrics to sing on a program. Young people want to create and discuss but are silenced. Flow swiftly? More like drift along in a canal that you’ve carved,” one netizen commented. “How about cutting housing prices and raising salaries for the rear waves? The rear waves are drying out,” another comment read. “Only those with financial means can have dreams,” a user posted on Weibo. “We are more of a “chive wave” jiulang, than a rear wave.”

Chive wave, jiulang, is a compound of rear wave and another viral phrase—cut chives, or gejiucai 割韭菜. Once a stock market metaphor, to describe how inexperienced investors reinvest in the stock market after loss, then a corruption metaphor, to capture how corrupt officials spring back in spite of regulation, “cut chives” is now mostly deployed in reference to young people, who stubbornly grow upwards, only to be cut down, again and again, from burnout, competition and disillusionment with the system. Unlike the rolling waves of the Yangtze, a symbol of continuous progress, cut chives embody the opposite, a symbol of despair and futile growth.

The disparity is jarring. Where is the divide? Down the lines of socio-economic class, geographic location, or political positioning? Who sincerely perceives the next generation as powerful rear waves, surging forward to assert itself? Who, in contrast, believes that growth is cyclical and futile, like frail weeds sprouting on barren land? Where does the true source of energy lie—in the aggressive power of the nation state, or in the hard-headed resilience of the people themselves? To what extent are they at odds, and to what extent do they fuel each other, entangled in mutual embrace?

Chives are banned at Tesla China as the carmaker wishes to avoid any association with the common saying ‘cutting chives,’ which refers to the exploitation of investors by a company. Every time an employee says the word ‘chives’, they are said to be fined CNY10 (USD1.50). pic.twitter.com/IjnqFHFcsS

— Yicai Global 第一财经 (@yicaichina) September 23, 2020

Yan: “Rear Waves” was Bilibili’s clumsy attempt to define their user base as a “young generation full of positive energy.” The company successfully got several official media houses on board to circulate the video, including a 2-minute version aired at the primetime slot just before the 7pm news (新闻联播) on CCTV-1. It backfired partly because it completely turned a blind eye to the bleak reality young people actually live in. But such a video with high production quality and self-righteousness was destined to face pushback, because it just wouldn’t vibe with the user base on Bilibili, the platform that popularized playful 鬼畜 and danmu bantering. Ultimately, it’s more of a feel-good video for Bilibili Corporate to present itself as a platform that’s cultivating a new generation that is creative, driven and full of ambition.

Kuaishou does this too—despite constantly being made fun of as a 土 (“low”) platform, it tries very hard to brand itself as a short video app that “gives voice” to people who live in rural areas and offers economic opportunities previously inaccessible to farmers and migrant workers. So I wonder, what was the target audience Bilibili had in mind when they produced it? Regulators? Investors? Parents??

GenZ didn’t need to be told by a boomer who they really are.

Krish: Rear Waves is a good example of how so much of what we find interesting on the Chinese web happens at the level of the 'reply.' A meme culture sustained, somehow, by both paranoid and reparative readings. Which I guess is why concepts like positive energy (正能量) encompass not just what is created, but also responses to them.

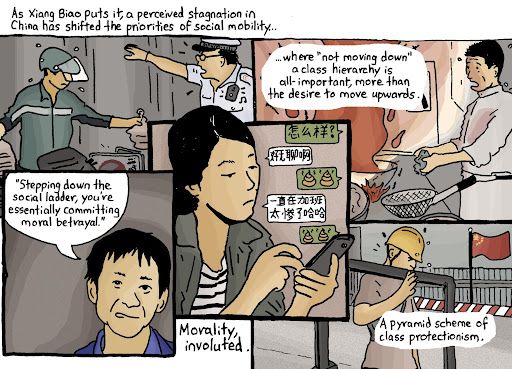

Simon: It does definitely feel like today’s “rear waves” are having some trouble pushing to the front. Despite younger generations growing up with more opportunities than their predecessors, chances to jump a social class or reinvent yourself completely by hook or crook seem to be scarce. There’s more of a script to follow to be a white-collar, middle class professional (which in a way is good), but it seems nearly impossible to somersault out of that cycle, which might have been doable in the heady days of the 80s or 90s.

To use contemporary art as a slightly abstracted example, most major Chinese artists are pushing 50. While there are a handful of artists in their early 40s that have just about reached the same status, below that there’s a gap—an artist in their mid-30s might still be considered “up and coming” even though their predecessors were participating in major international shows at the same age. The “secret sauce” that made established stars—participation in quasi-dissident activities in the 90s and a more open attitude towards China in the West leading to cosigns from foreign tastemakers with a knock-effect at home; enough time having passed for these dalliances to not be a liability now; and strong relationships with major art academies in China—seems hard to replicate in this day and age.

While people today are growing up in a time of unprecedented prosperity, the ladder that leads to the heights of that prosperity seems to have been kicked out of the way.

Perhaps this explains in part the obsession with 风口 (fengkou) which Yi-Ling explored in an earlier Rewilding: it takes a freak accident of the zeitgeist to bust out of the status quo.

Krish: Outro music this week is an overlooked album from last summer that I’ve taken to describing as “lo-fi math rock to chill out to.” This is Chengdu band FAYZZ with the appropriately titled “Freedom is Worthless:”

Tianyu: Happy Spring Festival, and see you in the Year of the Tiger!

Krish: Bye!

Yi-Ling is an aspiring gardener trying to re-grow her own glass jar chives.

Simon is (not) “hot, young and confident.”

Krish is a comic book artist in Chaoyang. He prefers No Wave to Rear Waves.

Yan dreams of chive pockets 韭菜盒子, not chive waves.