In the house this week: Yan, Zoe, Jason, Krish, Tianyu, Lisha, Aaron, Caiwei, Jaime, and Simon.

This dispatch appeared in S02 Episode 6, along with Shaxian Can't be Fucked With by Zoe. Cover illustration by Krish Raghav.

Tianyu: Happy Year of the Tiger! Let’s talk about food.

Krish: Our two stories this week are about the everyday life of Chinese food, and how malleable, inclusive and wonderfully creative local adaptations of national food cultures can be. Too much of writing about Chinese food in English gets tangled up in issues of “authenticity,” and the subjects of both our stories resist definitions of the authentic so fiercely that the word might as well be useless.

Jaime: Authenticity is for nerds.

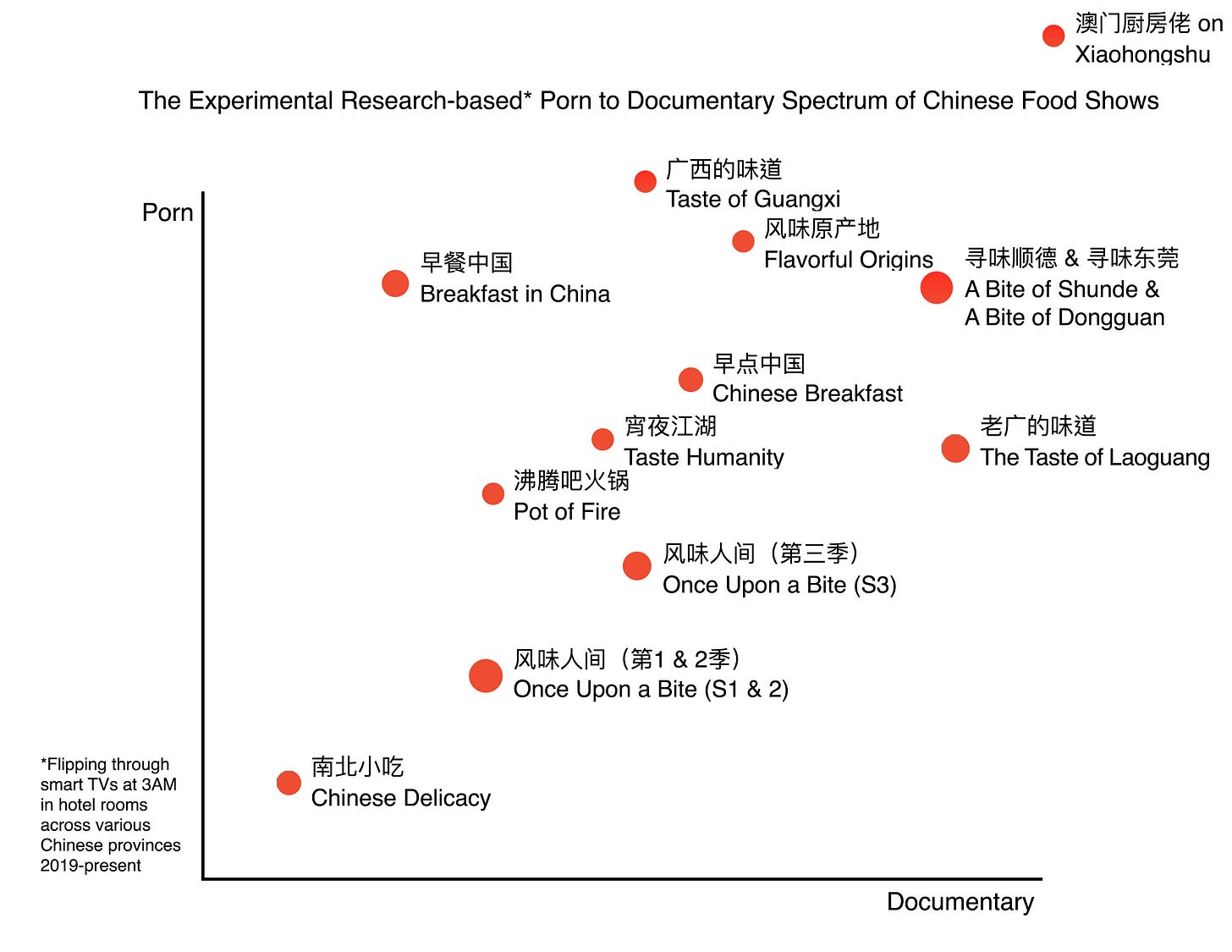

Krish: First, Yan goes into an internet rabbit hole to find Tahini-Linguine Hot Dry Noodles.

Meanwhile Zoe writes an ode to Shaxian Delicacies—China’s best drunk food staple.

Neither would feature in any traditional depiction of Chinese food, but I always think of this perfect parody of A Bite of China where the making of instant noodles is an epic adventure:

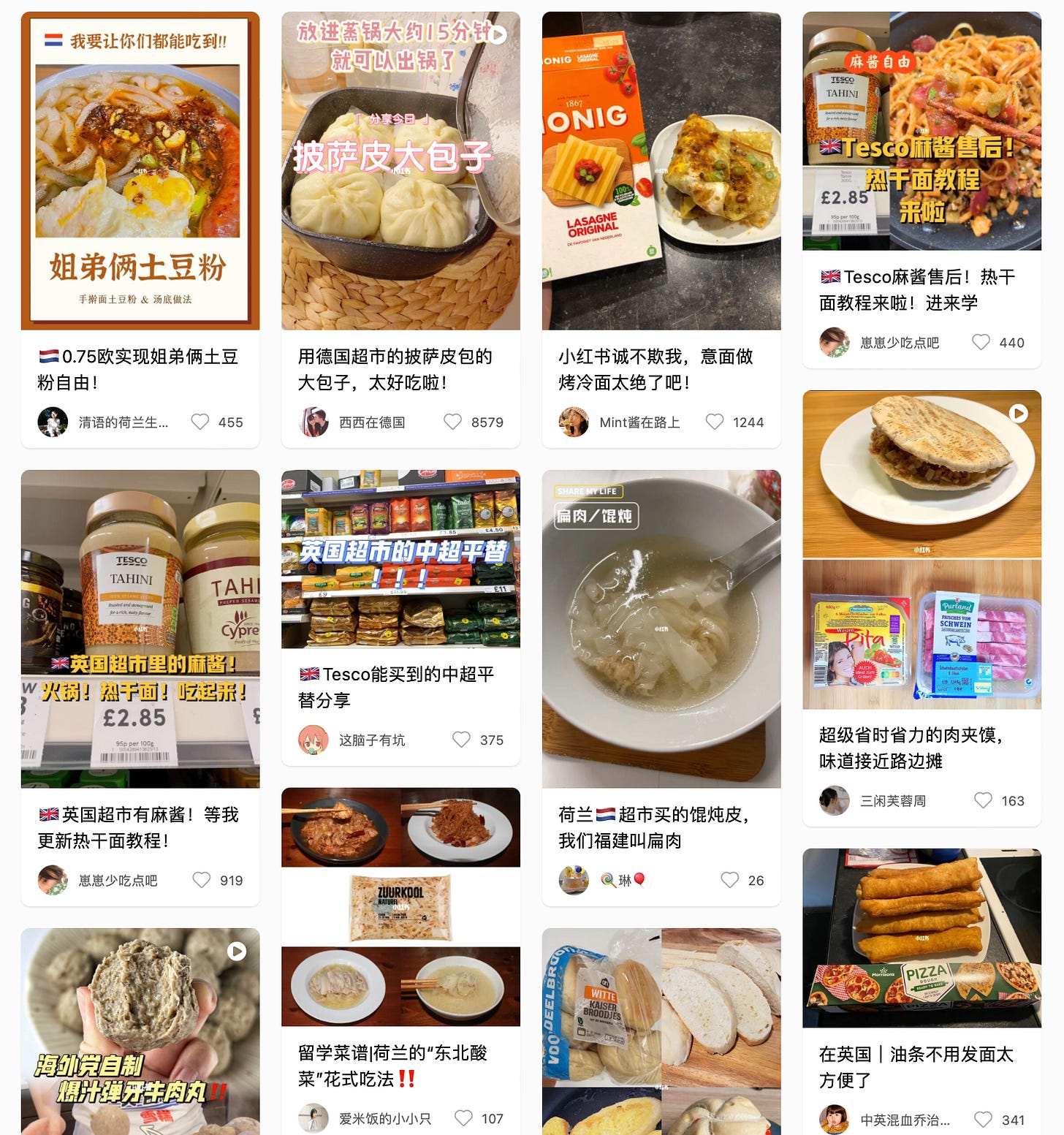

Food cultures are sustained by everyday adaptation and sharing, what the writer A.K. Ramanujan calls “an infinite use of finite means.” On the social platform Xiaohongshu (小红书, also known as Red), Yan discovers sharing that resembles a form of homesickness mutual aid:

Yan: It all started with pizza dough.

I was scrolling through my feed on Xiaohongshu, my go-to Chinese social platform for life hacks, or more specifically, recipes for Chinese dishes created by and for overseas Chinese. A photo of youtiao popped up. Beneath it the headline read, “Newbie friendly! Make delicious youtiao with pizza dough.”

I was shook. I’ve never associated pizza dough with youtiao. I’ve never associated pizza dough with anything other than pizza.

Since I moved to Amsterdam last September, I’ve been consuming Xiaohongshu as a sort-of productivity/home decor/inspiration blog. Although it is known as a platform full of fashion influencers who help sell clothes and cosmetics to a predominantly female user base, small niches have emerged in its culture that encourage all kinds of sharing: from “10 IKEA products every home should have” to “5 tricks that help you to write a literature review in an hour.” A news story pointed out that parts of Xiaohongshu resemble TripAdvisor or Wirecutter. A podcast even called Xiaohongshu the Zhihu (a male-dominated Chinese equivalent of Quora) for women.

Using Xiaohongshu feels a bit like playing with the bastard child of Instagram and TikTok: photos and videos show up on my “Explore” feed in an endless scroll. From my experience, it seems like the Xiaohongshu algorithm is a bit smooth-brained: it just doubles down on content you’ve shown any interaction with. So my pizza dough encounter opened up an entire genre of cooking among overseas users on Xiaohongshu that had been unknown to me: Ingredient Substitution (食材平替).

My feed was never the same again. I'm now obsessed with the genre.

Imagine you’re a Chinese student living abroad. You’re on a limited budget, and your access to ingredients is limited. Pandemic and supply-chain restrictions mean care packages and trips home are impossible. The food you’re craving isn’t “restaurant food” but rather regional specialties or niche, home-cooked dishes.

Enter 食材平替, “Ingredient Substitution.” The classics of the genre represent people’s diverse daily cravings that a regular Chinese restaurant can’t fulfill, existing at the venn diagram intersection of “cheap”, “possible” and “satisfying.”

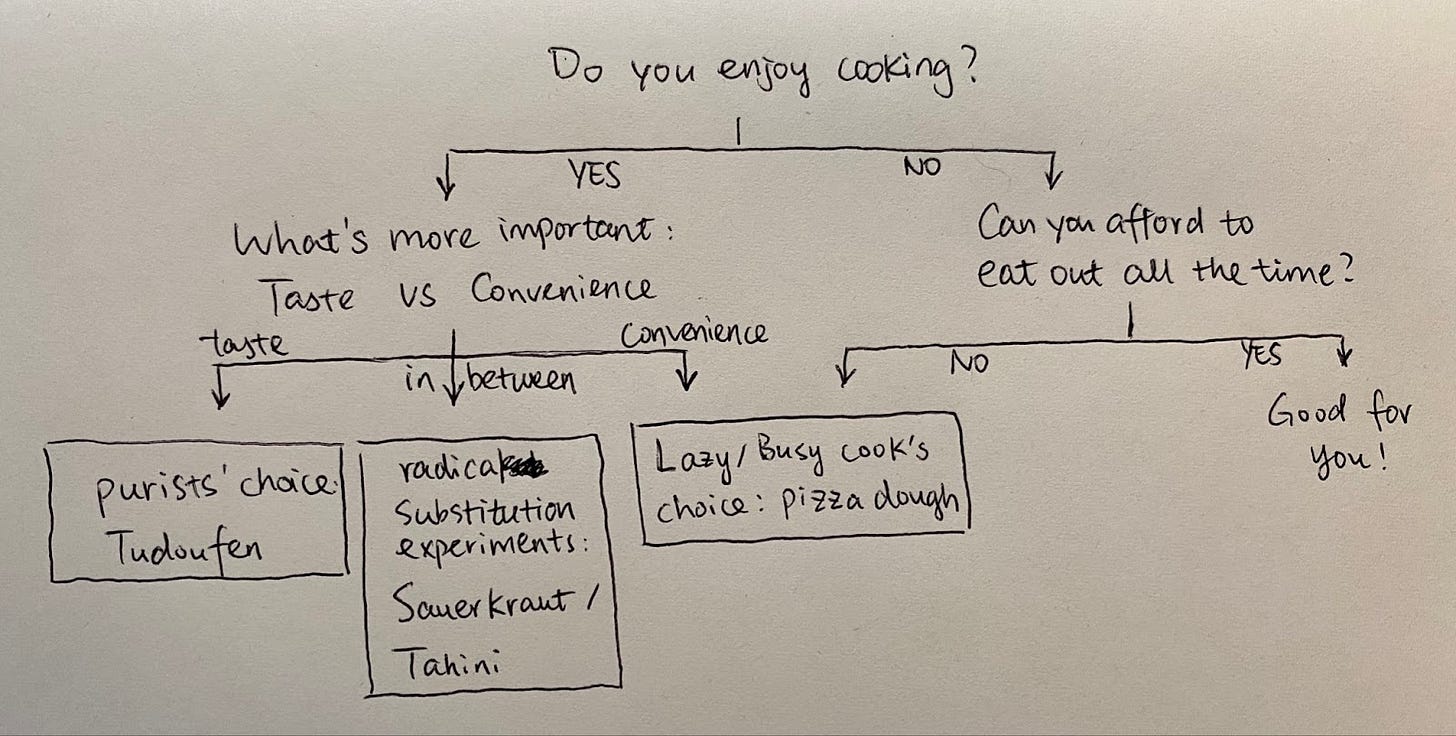

Before we dive into its three sub-genres, follow the flowchart and see which category you fall into:

Lazy/busy cook’s compromise - Pizza dough for youtiao/baozi/xianbing

Pizza dough embodies the first school of thought behind ingredient substitution: maximizing taste with a minimum amount of time and effort. A purist may frown upon this style of cooking, but it’s the perfect solution for people who don’t want to, or don’t have the time to, get their hands dirty. Pizza dough saves you the trouble of measuring flour and water, getting all the wet bits off of your hands when mixing the dough, and hours of waiting for a dough to rise. You speedrun the process by getting it ready-made in a grocery store.

Cooking with pizza dough also takes speedrun’s underlying logic: it requires imagination and an understanding of the object at hand in order to take advantage of it. Like speedrunners exploiting common bugs in game design, Xiaohongshu users take advantage of pizza dough as a premade mixture of flour, water and yeast, and repurpose it for making any flour-based dish.

I’ve made Beef pancakes and Shengjian Bao with pizza dough following recipes I found, and both attempts were successful. The outside was crunchy and golden, and the stuffing juicy. They weren’t perfect—I wished the dough had risen a bit more to give it a fluffy texture on top of the crunchiness, but they did the job. 8/10 would dough again.

Caiwei: This is the same “decompose rearrange” shit Chinese cooking (especially baking) enthusiasts have been seeing for a few years—I think essentially a result of China's yet undeveloped food industry, and also caused by a disparity in shared knowledge on food, especially when it comes to pastries. A good example is using ready-to-eat shou zhua bing (手抓饼, often translated as “pancakes” but come on it’s a paratha and even Jay Chou knows) dough to make Palmiers or egg tart crust. You cannot buy puff pastry at Chinese grocery stores, but you would have better luck finding frozen shou zhua bing even at the store in the smallest Chinese town. The substitution is amazing and uniquely diasporic because it takes knowledge from both food culture and a good amount of reverse-engineering/code-cracking, and reveals this deep resonance between cultures remote to each other, which I find beautiful.

Radical substitution - Sauerkraut vs. Suancai; Tahini vs. Hot Dry Noodles

Yan: Radical substitution has the most “fusion” potential. I call it radical not because it dramatically changes the cooking process, but because it’s the most adventurous and creative sub-genre in breaking boundaries between ingredients and national borders, challenging people’s preconceived idea of cuisine-specific ingredients.

Sauerkraut can be remixed as suancai (酸菜) in dishes from northeastern China. Tahini can be appropriated as the main component for the sauce in Hot Dry Noodles (热干面), a Wuhan signature. Can’t find alkali noodles for authentic Hot Dry Noodles? Use Linguine for similar taste and texture. Miss midnight snack 烤冷面? Use Lasagna to recreate the infamous street food.

Here’s a hilarious example of the same principle applied to cooking equipment: when you have friends over to make dumplings together but have only one rolling pin, use wine bottles or bowls!

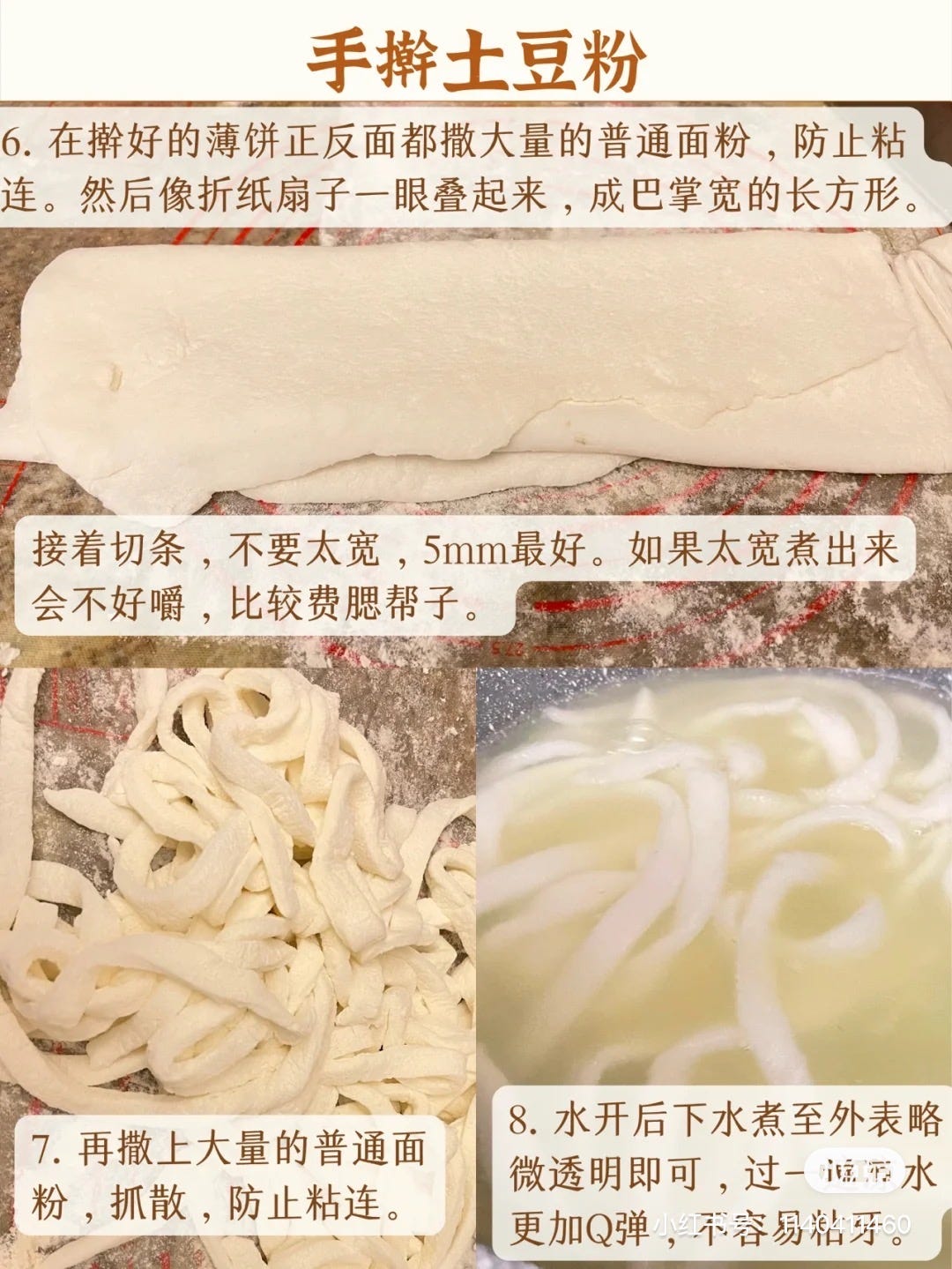

Reverse engineering - Making tudoufen from scratch

This last subgenre of cooking is the opposite of the first one: instead of taking a shortcut, it takes a detour. When ingredients hard to come by are not easily substitutable, or when a purist is craving for an authentic bite of their favorite dish, it’s possible to make some ingredients from scratch.

This accidental crossover with “slow food” does require more awareness of the ingredients themselves. It’s important to note that this kind of “first principles” thinking can be quite radical for casual cooks. Before I read the tudoufen (土豆粉, potato noodles) recipe from Xiaohongshu, it’s just a product I buy from dried food shelves in Asian groceries. I never thought about what it is made of, and how it is made: Mix potato starch with water and hit it up. Stir the mixture until it turns into a dough. The rest of the process is the same as making noodles.

Another advantage with this style of cooking is that it can be super cheap! As this recipe brags in the headline, “enjoy tudoufen at home for 75 cents!” With the global supply chain crisis, food products shipped from China are getting expensive—if you can even find them at all. If you’re a broke student who wants to save money, this is for you.

I can’t stop thinking of what Xuandi wrote in his senior fashion story in Season 1 last year. Influencers on Xiaohongshu usually want to sell you something, turning everything they touch into “derivative and banal” facsimiles. It is the opposite with Ingredient Substitution recipes: when specific products are mentioned, I never feel I was being sold something. I feel reassured that someone has tested it and successfully made a dish that I will one day make myself. Like senior fashion, they are creative yet unassuming: they aren’t monetizing their visibility or preaching shallow multiculturalism or in-your-face globalism. They’re not weaponizing nostalgia, but rather using it as an act of care, a way to feel more grounded wherever they may be.

At the end of the day, Ingredient Substitution is about living in a foreign country—adapting and getting by. Surviving and coping with the impossibility of going home. When I see a recipe being replicated, modded, or speedrun, I don’t see them as copycats trying to capture traffic and boost follower counts on Xiaohongshu. I see them as people who, in search of the old and familiar, have created something new.

Aaron: The exact same thing that happened to Yan has happened to me since I moved back to the US from Beijing late last year. Xiaohongshu is convinced that I’m a Chinese student living abroad instead of the 30-something white American that I actually am, and has delivered me a steady stream of Ingredient Substitution recipes since I demonstrated my interest by clicking on one of them.

Instead of Tesco tahini though, Xiaohongshu users in the US are particularly obsessed with Costco and Trader Joe’s, plus the occasional posts about Whole Foods. It’s been interesting for me to see, and has led to me using the app way more here than I ever did in China. In China, I’d find myself hate-browsing Xiaohongshu only if I was bored, but in the US I actively look forward to seeing the creative ways in which people can recreate the taste of home. It really does feel like a better, more creative version of Xiaohongshu. Now I just need to decide which one of these ten recipes for using Trader Joe’s uncured Black Forest Bacon as a Hunan la rou substitute I should actually cook…

Simon: In one sense Xiaoshongshu substitution cooking might just be the latest iteration of a longer process of the adaptation of food (foodways?) through immigration, itself speaking to the specificities of current patterns of migration. Subbing sauerkraut for suancai sounds fairly similar to the types of improvisation that created Chinese-American food. What might be different now is the class of the people doing this cooking, and, for some of them, the temporary nature of their sojourns outside of China. Will this become part of global Chinese cooking, but stay as a subculture for students, or is someone going to open a beef pancake place in Amsterdam that takes surprising cues from pizza and pide?

As a foreigner that’s spent a significant chunk of my life in China, I can relate to Aaron’s feeling of missing the flavors of a home that is not your home. One of my favorite foreigner-oriented media outlets in China is actually the YouTube channel “Chinese Cooking Demystified,” which I admit to binge watching and cooking from when I want to do something engaged with my surroundings, but also switch off the second-language part of my brain. Yet this is also strange, because part of the channel’s allure is about teaching you how to make inaccessible regional speciality/restaurant dishes while out of China—perhaps I am mentally preparing myself for departure… Anyway, I think they do a good job breaking down some of the differences between restaurant and home cooking, and actually have a video on making Shaxian Delicacies’ iconic peanut noodles. I have crisped green onions in lard to make it, which is pretty funny considering there is a Shaxian Delicacies 50 meters from my house. Imagining cooking it outside of China speaks to the power of nostalgia and distance, where something absolutely ubiquitous and mundane becomes alluring…