This dispatch appeared in S01 Episode 3, along with Xiao Hai Goes to RMB City by Jaime. Cover illustration by Xuandi Wang.

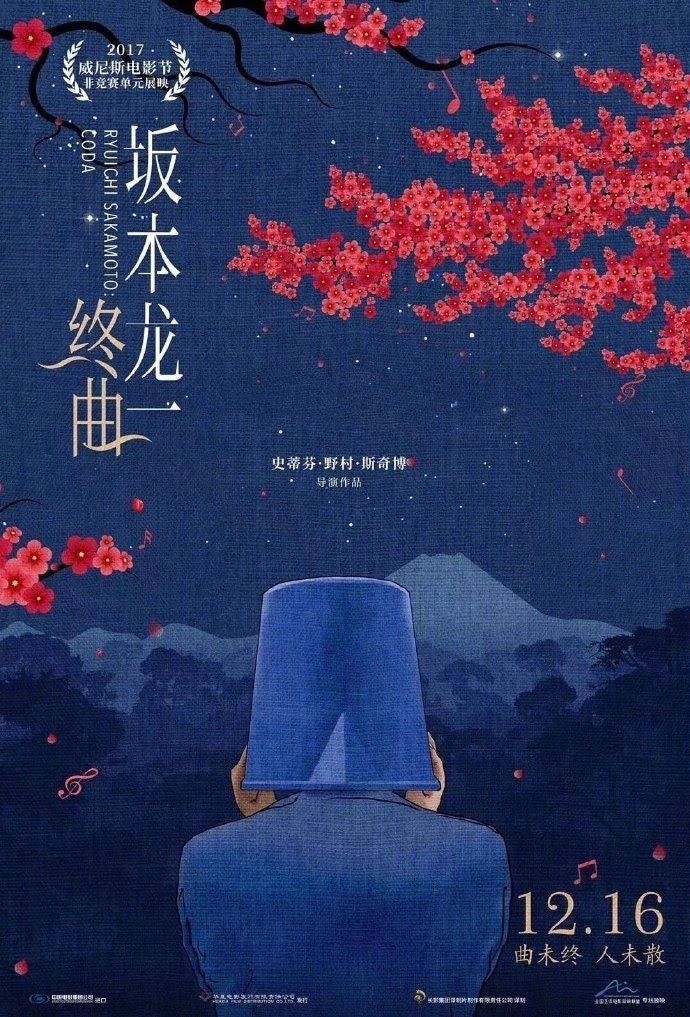

Simon: A few months ago, when Chaoyang Trap was transforming from an aspirational PowerPoint into a newsletter, I pitched Krish on writing something about the uses and abuses of Japanese musician Ryuichi Sakamoto (坂本龙一) within China’s cultural scene—basically, how through no fault of his own, he is desperately clung to by tastemakers trying to preserve their own relevancy and has inspired a fandom that seems to be the antithesis of his calm, refined aesthetic. This was bubbling into visibility because of the excitement around Sakamoto’s sound installation exhibition “seeing sound hearing time,” which was set to open on March 15 at M WOODS Hutong (木木美术馆) in Beijing.

Krish: You can make a pretty reasonable case that most “culture wars” on the Chinese internet are just battling fandoms. Sakamoto’s stands apart because this model of intense fan culture—usually reserved for pop idols—is transposed here to an experimental musician, one whose work has resisted bite-sized commodification and drip-feed worship. Yet it’s taken root, complete with a lucrative market for anything Sakamoto-adjacent. In 2019, his team even had to issue an official statement directed at fans in China, urging them not to believe anyone who claimed to be Sakamoto’s disciple.

The exhibition opening turned tragic, and a little weird. On March 9, a worker died after falling from the museum’s roof, a week before the scheduled opening. After days of silence, during which anger grew online at the museum’s active “management” of negative comments on Weibo, M WOODS and Sakamoto’s official social media accounts expressed their condolences and announced that in remembrance, the exhibition opening would be delayed.

Behind the scenes, you could see a classic instance of battling fandoms. M WOODS itself is an institution built like a pop idol, the epitome of wanghong (网红), an aesthetic designed to be a magnet for social media influencers. That, in turn, has bred a highly motivated group of M WOODS haters, driven both by the perceived shallowness of everything wanghong and a twisted misogyny against co-founder Wanwan, an art collector and model responsible for the museum’s online clout. In between was Sakamoto’s own fandom, torn between defending their idol’s reputation and salvaging a chance to see his life’s work. While the cause of justice for the worker’s death was taken up by a few activists, in music circles this tension mostly manifested as an uncomfortable silence as the issue raged. In days, the tragedy that sparked it was abstracted away as a vague “incident.”

After further radio silence, M WOODS finally announced over WeChat on Friday March 19 that the exhibition was now open—without any mention of the events that led to the new opening date.

Simon: Without being disrespectful towards the deceased and this sad situation in general, I thought it might still be meaningful to ask how we got here. Sakamoto’s exhibition was hugely ambitious, bringing in technicians from overseas in the middle of the pandemic who underwent weeks of quarantine. So what makes him such an attractive figure that this exhibition had to go ahead? Why not just work with a Chinese sound artist, when institutions face not only logistical issues but also a not-not-nationalistic cultural climate?

To be clear, though the cultural scene may have a Ryuichi Sakamoto problem, there’s no problem with the man himself: his music is great, he’s stylish, and by all accounts a nice guy. It goes without saying that I hope he makes a speedy recovery from his recent bout of cancer. Nor is it too hard to see his specific appeal in China. His long career has intersected with the country at a few key points: before he achieved stardom in the synth pop trio Yellow Magic Orchestra, his 1978 debut album featured a Mao Zedong poem read through a vocoder, and quoted from the melody of “The East is Red” (东方红); as an actor he came to China to film The Last Emperor (末代皇帝) in the late 80s; and he performed in Beijing in 1996. So not only do indie kids embracing Bubble-era Japanese “city pop” love him, but so do an older generation of promoter-curator types excited that someone they remember from an earlier era is still relevant. That his music is now mostly field recording-driven ambient doesn’t actually hurt: though very good, it’s also easy to reach for if you want to appear to be a serious, intellectual person who listens to experimental music.

So where do things go too far? Sakamoto has inspired a highly specific kind of adulation, which, when closely examined, reveals gaps in China’s own music industry. His nickname in Japan since the Yellow Magic Orchestra days has been “Professor,” a moniker that has also been embraced in China, and even popped up in M WOODS’ marketing materials. But if Sakamoto is the Professor, what has China’s music scene learned from him?

——

Caiwei: It's worth pointing out that many of China's pop idols claim to be inspired by Sakamoto, and it would not take a lot of backtracking for Chinese pop music fans to discover Sakamoto as the “idol of their idol."

Yi-Ling: I’m fascinated by the idea that 1) adulation of a non-Chinese artist in China, is ultimately rooted in 2) a gap in the Chinese industry. Which begs the question: why can China never have its own Professor Sakamoto? Which in turn makes me wonder, why does it seem like, when it comes to cultural conversations about China, that we are always asking some iteration of the question of: “why can China not have its own...Chanel/ Kendrick Lamar /Burning Man/ Oscar’s/ [insert globally recognized cultural icon/artifact that somehow, in spite of its population of 1 billion, China is incapable of producing]? Chinese hip-hop, in particular, consistently asks a variation of the question, "Can China produce its own Kendrick Lamar?"

So what is the secret sauce missing in the cultural ecosystem that won’t allow homegrown icons to rise to the surface?

——

Simon: On one level, the answer is obvious: the infrastructure for commercial popular music in mainland China was limited at the time when Sakamoto’s career began, and it would have been financially impossible for someone to experiment with the cutting-edge electronic equipment he used. But things are different now—so why does the enthusiasm of tastemakers like Beijing radio DJ Zhang Youdai (张有待), who has been trumpeting his “friendship” with Sakamoto since the 1990s, give the exhibition the air of a “homecoming?” Why is Sakamoto’s tacit acknowledgment still so important?

There are actually examples closer to home of people pop enough to be famous and arty enough to be respected, yet for a variety of reasons none of them seem perfectly “professorial.” Faye Wong (王菲) arguably remains Greater China’s hippest pop star, but from a business perspective is too big for the projects Sakamoto is involved in (and after recording the theme song to a propaganda film in 2019, maybe shouldn’t be considered that cool?). Dou Wei (窦唯), who was briefly married to Wong in the 90s, seems particularly Sakamoto-esque, for how he started his career with a hair metal boy band (黑豹乐队, Black Panther) in the late 80s before recording goth/post punk tracks in the early 90s, and then shifting gears again into post rock, ambient, and even Buddhist black metal. But today he doesn’t perform live, and far from being renowned as a handsome older gentleman, is known as a slob who loves unhealthy Beijing breakfast and hates paparazzi. Thinking about Sakamoto’s soundtrack work, pop star turned experimental electronic composer Lim Giong (林強) immediately comes to mind—except he’s actually from Taiwan.

Caiwei: Fun fact: Wong’s song “What if You Are Fake (如果你是假的)” in her 2000 studio album Fable made a direct reference to Sakamoto in the lyrics:

“What if you look like Snoopy,

What if you are Mary, Julie or Charlie,

or Ban Ben Long Yi [Ryuichi Sakamoto],

Does it make any difference,

Will I still love you,

Will it be as sweet?”

Simon: To be fair, this type of problem isn’t unique to China. The way popular culture works has changed, and while there are more “weird” celebrities now, it’s probably harder for figures to emerge who, like Sakamoto or David Bowie, hold a wide appeal across multiple niche cultures. However, the Chinese culture industry’s obsession with Sakamoto, while being unable to produce their own equivalent (and not due to any lack of raw talent), is a bit embarrassing and speaks to the degree to which the scene eats its own young.

The iconoclasts of the 90s, an era of relative openness, didn’t have the chance to age gracefully, either selling out (Faye Wong) or opting out (Dou Wei). Pivoting back, the Mao quote on Sakamoto’s first album didn’t come out of nowhere, but rather from a tradition of left wing student activism in Japan. Though his views have changed, he remains an intensely political artist, rallying against nuclear power for example. This social consciousness lends a certain depth to his celebrity, perhaps making being his fan seem more meaningful. Taking such a stance in China, however, would amount to commercial suicide.

Today, when mainstream music is mostly a spectacle, and indie and experimental music are increasingly commodified as lifestyle experiences, one is left with a scene that possesses a considerable amount of money and creativity, yet struggles to present new icons that people genuinely connect with. This leads people to reach for compromise figures with wide appeal across different fandoms like Sakamoto, whose participation as an elder statesman also implicitly suggests that the scene is alive and exciting.

Yet working with someone from a different generation and culture opens up space for tension and accidents, or can be a missed opportunity to challenge a Chinese artist to grow to the next level. But perhaps that’s missing the point of Sakamoto’s appeal—coming from another context entirely, he floats above the humdrum compromises and endless negotiation that go into being a star in China. Unblemished by unfortunate realities, he lets us imagine something better.

Full disclosure, Simon works at the contemporary art museum UCCA in Beijing. It is worth checking out the other dispatch in the episode, an interview with migrant worker-turned-poet Xiao Hai, by Jaime: Xiao Hai Goes to RMB City.

If you haven’t, consider subscribing to Chaoyang Trap, a newsletter about everyday life on the Chinese internet. It’s a regular, usually fortnightly, exploration of contemporary China, one important niche at a time. We’re interested in marginal subcultures, tiny obsessions, and unexpected connections.

Paid subscribers get access to our special deep-dives and premium issues!

Simon Frank is a writer, translator, and musician in Beijing. He thoroughly enjoyed listening to Thousand Knives and B-2 Unit while contributing to this issue.

Krish Raghav is a comic-book artist in Beijing. He likes Haruomi Hosono more than Ryuichi Sakamoto.

Caiwei Chen is a writer, journalist and podcaster. She cooks with boxed ingredients but tries to finish all her dishes with a gourmet touch.

Yi-Ling Liu is a writer in Beijing. She likes to wall-dance—both online and at the climbing gym.