This dispatch appeared in S02 Episode 4, along with The Zine and the Unseen by Denni. Cover illustration by Krish Raghav.

Jaime: When it comes to lack of creative agency, respect, and fair treatment, the one profession in the creative class that might universally have it even worse than media workers might be translators. It took someone like millennial literary phenomenon Sally Rooney to remind the reading world of the inherent political value in literary translation when she turned down a recent Hebrew translation offer from an Israeli publishing house as a gesture in support of the Palestinian struggle. The wildly successful Irish novelist was once compared to Uniqlo for “the era of normcore fashion has been matched with an era of normcore literature”. But are the post-90s and post-2000s kids who line up for the opening of the new Sanlitun Uniqlo global flagship concept store with “in-store curated LifeWear experience” the same millennials who wear “cheap Uniqlo cashmere sweaters to his semi-leftist politics job” or past season Uniqlo U by Christophe Lemaire to gallery openings and dinners their mentors pay for from selling out before it was normalized?

Is Sally Rooney the undeniably universal millennial experience as the rest of the world claims? I caught up with Na Zhong, the Simplified Chinese translator of Sally Rooney’s three novels to date, to get some perspective on how Irish are her novels for a Chinese audience, how does her prose hold up in translation, and who might be the Sally Rooney of contemporary Chinese literature (click bait!) Na was born in Sichuan and now lives in New York. Her writing and translations have appeared in AAWW, Lithub, and LARB and she hosts a podcast in Chinese about literature and translation. She has just finished the translation of Sally Rooney’s third novel, Beautiful World, Where Are You.

The Cloud in Sally Rooney's Room

By Jaime Chu

Jaime

How did you get involved with translation and translating Sally Rooney’s novels? Are you proud of it? What was the process like?

Na

I have very complicated feelings about being a translator. I majored in translation in college, so it was natural for me to pick up some projects to hone my skills. A friend I met through one of the projects introduced me to an editor, who was looking for a translator for a short story collection by an Irish writer named Billy O’Callaghan. I translated an excerpt from the collection and was hired. At the same time, I was never content being just a translator, because back then I didn’t feel respected being a translator and came to perceive translation as a sort of derivative. So I started writing for newspapers until a publisher who just bought Sally Rooney’s first novel, Conversations with Friends, reached out through a friend to ask if I would be interested in translating “this novel by a young Irish writer.” I finished the novel in two days and was completely hooked. I took on the project without realizing how big this will be in three years.

I basically witnessed how Rooney became the celebrity writer. It's a privilege and a pleasure—her first two books are extremely enjoyable to read and translate. Readability has always been one of her strongest suits, which also helps me as a translator to work with a rhythm. I’ve just handed in the translation of her third novel and I have some mixed feelings about it—I don't know if you have read this one or any of her other books.

Jaime

What were the mixed feelings?

Na

I love how she continues to experiment, using emails as a vessel to carry the characters’ interiority and playing with the Woolfian stream of consciousness technique. But when she goes into step-by-step stage instructions in the sex scenes, I found myself bored with having to come up with six ways to say “he smiled” in Chinese. That said, as I reviewed my translation last week, I couldn’t help but marvel at how she succeeded, once again, in capturing the power dynamics of relationships, the sharp edges and dark shadows that refuse to be tamed by overused words like “love” or “friendship”.

Jaime

Maybe I should experiment with reading the third book in Chinese first before English. I remember having different reactions when I read Conversation with Friends at different times a couple years ago. Recently, I read your translation in Chinese, and it hit me in a different way, because the language of her sentences are so direct, but in a way that you wouldn’t read the same phrasings and thoughts in contemporary novels by Chinese writers—for example, quite early in the novel, Bobbi says, “我是同性恋,而弗朗西丝是个共产主义者。” (“I’m gay, and Frances is a communist.”) So that felt very special, to hear these thoughts on the page in a different language.

Na

When I was translating that part, I was worried that it would get cut out in the final version. I was glad that it didn't. After the book came out, I joined another writer on a podcast about Sally Rooney and the host asked a question about Marxism, and it suddenly hit me that actually, what Sally Rooney meant by Marxism is quite different from what it means in China. Of course, they stem from the same origin, but the history of how it was received and taught is completely different, but I agree there's a connection there, a more subtle and complicated one.

Jaime

Building on that, I remember reading Sally Rooney reviews that comment on how despite their wide relatability as “millennial novels,” her books are in fact very Irish in the ways that they depict things like geography and class consciousness. How much of this “Irishness” did you feel when you were translating these novels? How deep did you have to go researching Irish culture?

Na

There are many moments when I had to do research because her characters are always talking about local politics. They are always dropping names that are unfamiliar to me, and her characters have extremely Irish names—Siobhan, Connell, Felix—a lott of them are impossible to find in my dictionary (《世界人名大词典》 is the official Xinhua dictionary for Chinese translation of foreign names).

But for me, these Irish elements feel like decorative icing on a cake, because the way her characters think and relate to the world feel extremely American to me, which is probably why the books are so well-received by U.S. readers, because they share so much more in common: They are hyper-conscious of themselves. Very outspoken about their political stances. They like to flaunt their intellectual superiority at each other. Rooney’s Irish characters are constantly talking about what’s happening in London, New York, and the U.S. in general.

I think in a sense, Twitter and social media platforms have created this shared space for English-speaking netizens, while because of various reasons, Chinese readers don’t have that easy access to the communal space and public conversation.

That’s an important factor in deciding how Sally Rooney has been accepted in China, versus in the U.S.

Jaime

Do you know anything about how her books have been received or accepted in China?

Na

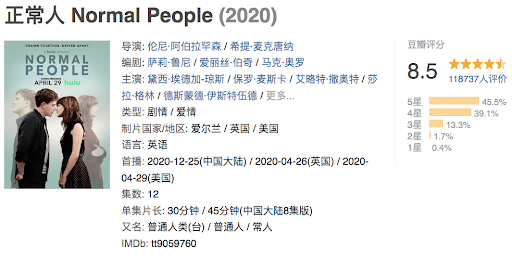

Normal People has been received very, very warmly, not only because the life depicted in this book is so much closer to Chinese readers, but also because of the TV adaptation. For Conversation with Friends, with its love triangles and bisexual relationships and extramarital affairs, these themes make some of the morally righteous Chinese readers very confused or offended. I feel like people are having more mixed feelings about Conversation with Friends.

Jaime

Do you track the Douban pages for reviews?

Na

I try to avoid Douban reviews for my own sanity. Like Goodreads, Douban readers are extremely picky. One interesting thing about Douban readers is that they would equate the poor quality of the work with the translator’s quality of work—basically, if something doesn't translate, say, culturally, usually they would say it's the translator’s fault. If the story is weird, or if it doesn't resonate with them that much, they would say, maybe it's the translation. The translator is a very easy scapegoat for the mediocrity of the work.

Jaime

Have you observed any similarities between Rooney’s sensibilities and the work of any contemporary Chinese writers?

Na

In terms of the kind of concerns shared by the millennial writers in the West, I haven't found anyone who is super similar to Sally Rooney. I have an impression that Chinese literature in general does not approve of individualism—young writers are encouraged to write about the society, the past, anything but themselves. On the other hand, Rooney’s work is deeply rooted in individualism, especially in her third novel, where the loneliness of the characters are examined to an almost painful degree. They are like atoms drifting in the world, disconnected from their families. They maintain superficial relationships with coworkers and only choose a select few to bare their hearts. For Chinese, I feel like we have a much closer relationship with families, which is both bondage and a sort of shelter, a place to seek refuge when you are defeated.

When I was translating Conversation with Friends, I was also working on my own novel, and there was a time when I would try to write more like her. But I struggled and failed, because it was impossible to impose her glamorous style on my unglamorous characters—how can they talk like that? My characters either rarely show the cerebral side of them or simply don't have this side to them. They care about different stuff, and they are definitely not good-looking.

The level of interest in themselves shown by Sally Rooney’s characters would risk being criticized as self-absorption in Chinese literature, which is why I haven't seen any young writer who writes in a similar vein. But a new generation of Chinese writers are emerging, and many of them are dealing with feminism and their relationships with the world in a very original way.

Jaime

It's interesting to think about the idea of the “millennial” even, because the way that generations are delineated in China is actually very different from how the millennial covers an age range. It’s not entirely fair to draw a direct analogy, so it's interesting to see how these experiences get reflected in literature. What would you consider to be representative of post-90 novels for Chinese readers?

Na

There are a couple of works by young Chinese female writers that I find very relatable. One of them is Wang Zhanhei (王占黑). In her first two short story collections, she pays tribute to her parents’ generation, elders from her community, but with her latest short story collection, she's focusing more on people around our age.

Another Chinese female writer called Lu Yinyin (陆茵茵) depicts young Chinese women's experiences in a very subtle and lyrical way, which I quite like.

Jaime

What you said about the atomized experience of being a young person today, I thought of a 2020 film called The Cloud in Her Room, which is a frank, compact, and “self-absorbed” story of a recent college graduate returning home in Hangzhou. She presents a disaffected front in reaction to almost everything that's happening around her, while inside, she is actually questioning and seeking release from the familial or emotional ties that get formed simply by being human around other people.

Na

When I was translating Conversations with Friends,I was remembering what I was doing as a 21-year-old. It was such a boring life. A lot of reading and finishing assignments and trying to be a good student, even though I was already in college. To my regret, a lot of us have a very long puberty period where we don't make decisions on our own. We just follow the mainstream and what our parents have told us to do. It’s definitely an interesting thing to think about.

Krish: Outro music this week is amazing new Beijing band KyoYoKo. They write nervy, jittery, doomed songs for tangping youth. “Untitled #27” wouldn’t be out of place in a Sally Rooney book:

Jaime is an editor who lives and works in Chaoyang.

Na is a bilingual writer, literary translator, and cultural podcaster based in New York. She prefers clothes with pockets.

Krish is a comic artist in Beijing. He’s really into jan sober but otherwise makes very poor fashion choices. Ask him about artisanal bowties.

Simon Frank is a writer, translator, and musician in Beijing. He hopes that Christopher Lemaire might one day hear his music.