In the house this week: Yi-Ling, Even, Yan, ████, Krish, Yuyang, and Simon.

Yi-Ling: Rewilding is an exploration into the language of the Chinese internet.

In each issue, I pick a word from the labyrinthine swamp of online life in China, lay it on the table, scrutinize it and take it apart in the form of a mini-essay, then replant the pieces, sowing seeds for further conversation.

This week: 风口-pop philosophy.

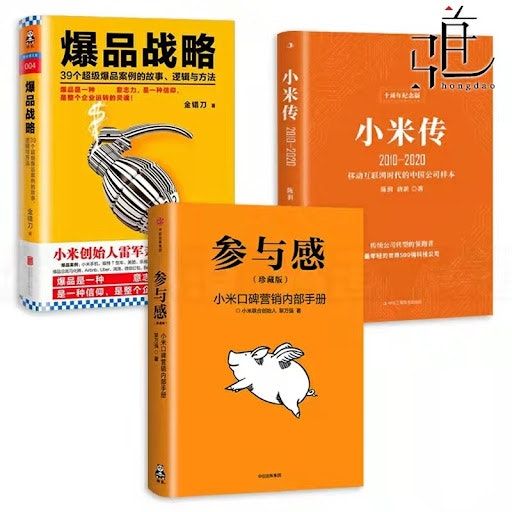

Six years ago, Lei Jun, the founder of smartphone giant Xiaomi, shared a few secrets to his success with The Wall Street Journal—words of wisdom that would become forever immortalized in the lexicon of overeager Chinese techies and investors.

“Even a pig can fly,” he said. “If it stands in the middle of a whirlwind (fengkou.)”

“站在风口上,猪都能飞起来.”

Literally, fengkou translates into “wind vent,” an opening through which the gust can blow. To step on a wind vent is to stumble upon a path to profit, to open sesame your way to the pot of gold. In other words, any clueless entrepreneur can succeed, as long as they seize the right opportunity. After all, Lei Jun did it. Swept up in the zephyr of his generation—the rise of the mobile internet economy in the late 2000s—he built Xiaomi, a company named “Little Millet” for its ethos of hard work and humility, into one of the largest smartphone companies in the world. If he could do it—if Jack Pony Robin Yiming could all do it—then you could do it too.

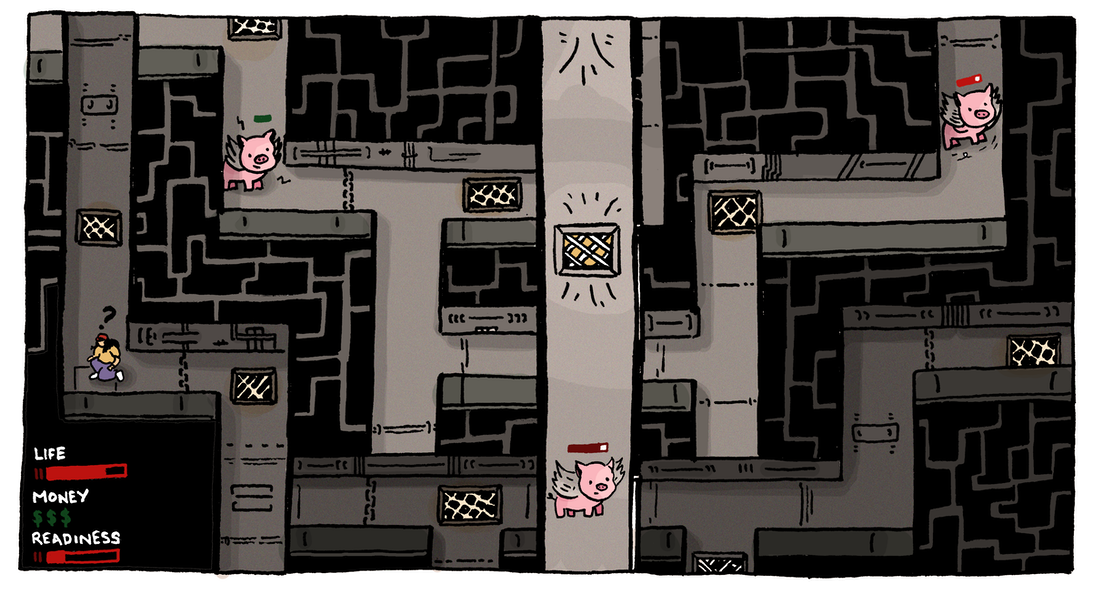

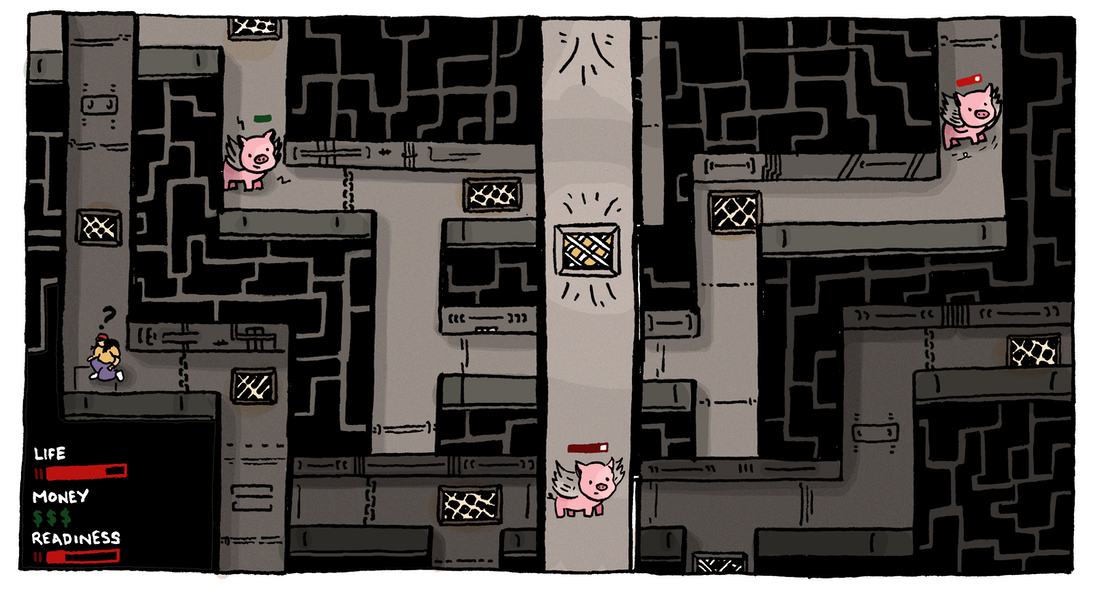

People devoured Lei’s words. Suddenly, everyone was on their pudgy haunches, hungrily sniffing out the next wind vent. Everyone wanted to be a flying pig. Professional investors zealously debated where they could find the next wind vent. EdTech! Social e-commerce! Rural e-commerce! Virtual Reality! Bitcoin! Amateur bloggers shared extensive wind vent breakdowns, developing Lei Jun’s words into “Flying Pig Theory,” and comparing its philosophy to Sun Tzu’s Art of War. Ofo! Mo-fo! P2P! B2B! NFT! “Everyone’s dream is to catch a wind vent,” wrote a Zhihu blogger, in a post titled ‘How Do Ordinary Folks Catch Wind Vent Industries. “You just need to be ready.”

Readiness is the core idea behind fengkou. That in order to succeed in an environment as fast and capricious as China’s, where the weather changes and the winds shift to forces completely outside of your control, you have to be ready. In contrast to their Silicon Valley counterparts, Zhongguancun veterans know that the key to a start-up’s survival is not “mission-driven” but “opportunity-driven.”

Yi-Ling: Don’t go against the grain to fight for your values; go with the flow. Ditch software; go hardware. Dump the edtech stocks; buy the electric vehicle shares. Move from first-tier city to second tier to the countryside. Urbanite slump; rural revitalization. When the window opens, pivot to livestreaming; when it shuts, pivot to healthcare. Pivot, pivot, pivot like a Daoist piggie, caught in a tornado, praying that you’ll end up somewhere good.

But today, given the sweeping Crackdown on Everything that we’ve seen in the last few months, we are living in profoundly different times. Fengkou entered our lexicon in 2015—the glory days of tech entrepreneurship, back in the days when 996 working hours were worn as a badge of honour and CEOs were worshipped like rock stars (throwback when one such CEO belting “Can You Feel the Love Tonight” in a white wig and tight-fitting red jacket in front of roaring crowds.) Ever since Jack Icarus Ma flew too close to the sun and disappeared from the public eye, all around us, little piglets have been raining down from the skies.

If the 2010s were the decade of the Flying Pigs, then do the 2020s mark the beginning of the Falling Pig? In today’s China, will there still be wind vents? Where will we still find them, what will they look like, and most importantly, who will still have the balls to seize them?

Even: So for work related reasons I’ve sought out agriculture-related expressions for years. I was struck, reading this, that when I first learned this one (back in like 2007 or 8) it was rendered “台风来了,连猪都会飞”—when a typhoon comes, even pigs can fly. But a typhoon is a natural disaster without redeeming qualities, which makes me think that Lei took this phrase that referred to a destructive and chaotic thing, and neutered it by revising the expression to 风口. This draws focus to the funny, hopeful image of the pig flying, but not on the mess it will face when it inevitably falls back to earth.

I can’t figure out exactly where or why I first heard this typhoon version, but apparently Zhang Ruimin, the founder of appliance company Haier, popularized it back in the mid 2000s.

████: I think there’s a very fine line between just “trends” and a true 风口—the real vents come on the back of venture capital. The wind that pigs are flying on is money: investors don’t just find wind vents, they make them, and that’s not going away any time soon, even if the industries change. F&B has been a huge one lately, with trends like the themed restaurants linked in the video above prefiguring today. The wind picked up this year with stories of people taking investment to open restaurant chains directly into their personal accounts before they even registered a business. But the flip side of the saying is true: wind vents can even make pigs fly. I went to one of the VC-backed noodle chains and they made me order with an app for a bowl that tasted like slop.

Krish: “Fengkou = trend + VC scramble” is pretty accurate, but it’s also a very particular kind of scramble that seems to result in identical, destructive consequences regardless of industry. Be it dockless shared bikes or EDM music festivals, there is first ridiculous oversupply, then a ridiculous overcorrection.

Yan: I’d add government policy to the fengkou equation, something like:

Fengkou = (Trend + VC Scramble)*Government Policy

Like Yi-Ling said in the piece, with the crackdown right now, there are trends, but no fengkou. Trends can be set by some wanghong, but it takes capital blindly chasing trends to have fengkou, which we don’t see nowadays. And I think the important factor here is government policy. Back in 2015, the government was campaigning for “Internet+” and anyone who could come up with a PPT that combines a traditional industry with the internet (O2O, a.k.a “offline-to-online”) could get some investment from VCs in Zhongguancun, which was the genesis of this photo story Yuyang Liu and I did at the time:

████: If you have any good PPT-based grift ideas, please do get in touch with Chaoyang Analytica LLC.

Krish: Building on ████’s example, there is definitely a fengkou emerging in dive bar chains. The founder of Starbucks-for-vodka-shots chain Helen’s recently became the country’s latest billionaire, and here is Shenzhen’s Helens-but-craft-beer chain RichKat (猫员外) just openly boasting about how much money they have.

Simon: I think the fengkou paradigm is emblematic of how many businesses are oriented not towards specific products or services, but precisely as businesses. To follow this F&B line of approach, I believe I heard that due to the new regulations on tutoring, one teaching company has started selling food. Or when 螺蛳粉 (luosifen), Guangxi’s pungent river snail rice noodles, peaked in popularity during quasi-lockdown last year, unexpected parties got involved, from back-to-nature influencer Li Ziqi (李子柒) launching her own luosifen brand (despite not being from Guangxi), to McDonalds and KFC adding pickled bamboo (a key ingredient in the dish) to burgers.

The connections to CEO antics that come up here also remind me of a point that I think isn’t talked about enough—outside of China, it’s easy to fall into the “dissident” narrative that if Pony Ma and Jack Ma somehow fall foul of government guidelines, it means they’re doing something good, some kind of resistance. But things are more complicated. I feel like they guide the direction of mainstream values and trends—and also occasionally, temporarily, fall out-of-step with the (official) direction of society, resulting in a slap on the wrist. These guys do seem pretty kooky, and their framing can seem strange at a time when hardly anyone looks to Zuckerberg or Bezos for moral guidance.

Yan: I completely agree, because these companies, in a way, are always trying to align their business with the priorities of government policies, either to directly get funding from local governments, or at least to get support and preferential treatment. For e.g., all the “rural e-commerce” startups, or even short-video app Kuaishou, frame themselves as poverty alleviation efforts.

Yi-Ling: New Oriental—China’s largest tutoring company—has pivoted to selling vegetables. TOEFL to tomatoes. New fengkou? Eat your greens, folks.

Yi-Ling Liu is a writer in Beijing, but would like to exist somewhere warmer.

████ is a ███████ and ██████████ at ███████ in ███ , and prefers his noodles without the taint of venture capital.

Yan Cong is a Beijing photographer now based in Amsterdam. She believes that Substack should start paying more writers instead of charging fees with their $65 million venture capital money.

Yuyang Liu is a Chengdu-based photographer. He needs hair and sleep.

Krish is a comic book artist in Beijing.

Simon Frank is a writer, editor, and musician in Beijing. He misses all Chaoyang exiles.

Even analyzes pig policy and can authoritatively confirm that swine wings are not yet eligible for local or national subsidies.