This dispatch appeared in S01 Episode 5, along with “ZQSG for YYDS”: How Idol Fans are Made by Yan Cong and King of Fairy Tales, King of Posts by Tianyu Fang.

Sridala: After Chinese TV drama The Untamed (陈情令, “CQL”) took the world by storm in 2019, international fans clamored for all kinds of adjacent media: the original novel and all its adaptations, endless thirst-feeding interviews, and reality show appearances by actors promoting a drama.

International fans—ifans—who speak not just Japanese, Korean, Thai, or English, but also Portuguese, Spanish, German, or Tamil want to know a lot of things: what the actors in a behind-the-scenes were giggling about; what this or that slang means; what kinds of adaptation censorship allows. Enter the Chinese fan—the cfan—who is not just a translator, but a virtual cultural guide.

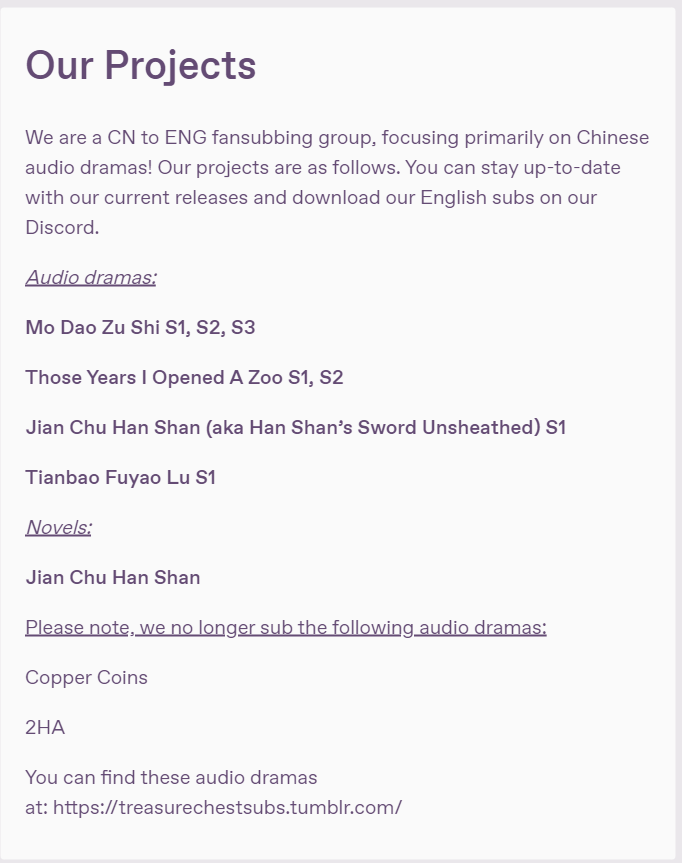

Fan translations are nothing new, of course, but the popularity of CQL meant cfans were generating a lot more material for ifans: drama meta, yes; but also translations of audio dramasand even the rare interview with authors. A committed fan, could even find AO3 translations of fanfiction published on Lofter (乐乎).

Industrious cfans don’t just subtitle and translate, they also help ifans navigate the complicated media environment in China. If, say, an ifan wants to watch episodes of a drama as soon as it airs, she may have to subscribe on platforms like Youku (优酷) and pay for VIP access. Helpful cfans will provide guides on how to do this.

The relationship between cfans and ifans is unidirectional, though, and cfans probably know this better than ifans. As Tumblr blogger Big Red Panda said in a post, “It’s more a unilateral transfer than a conversation between different cultures.”

Cfans can offer ifans an entire chunk of the media experience in China, while ifans in return can offer…to open their wallets and consume a lot of this media legally—an aspect that’s pretty unquestioned by fandom, even as another subsection of it uploads drama episodes onto pirate sites.

The irony can’t be lost on anyone involved. A lot of the labour that cfans do is free, and completely unofficial. Yes, sometimes aspects of their translation may find their way into official subs, but the work they do is entirely separate from official media channels (although Bilibili just announced a dedicated site for their manhuas in English translation, where they credit teams that have worked to fan-translate works).

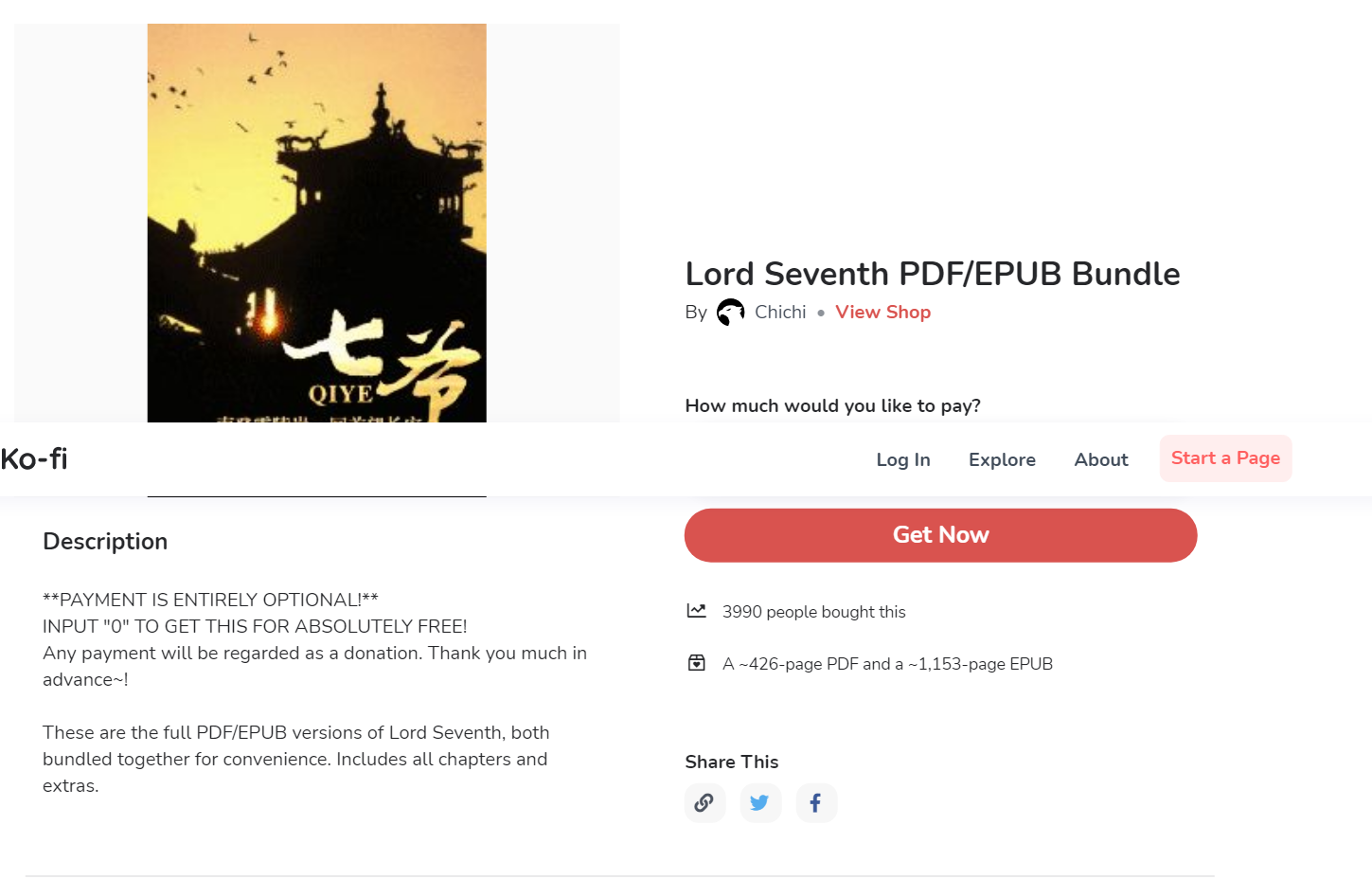

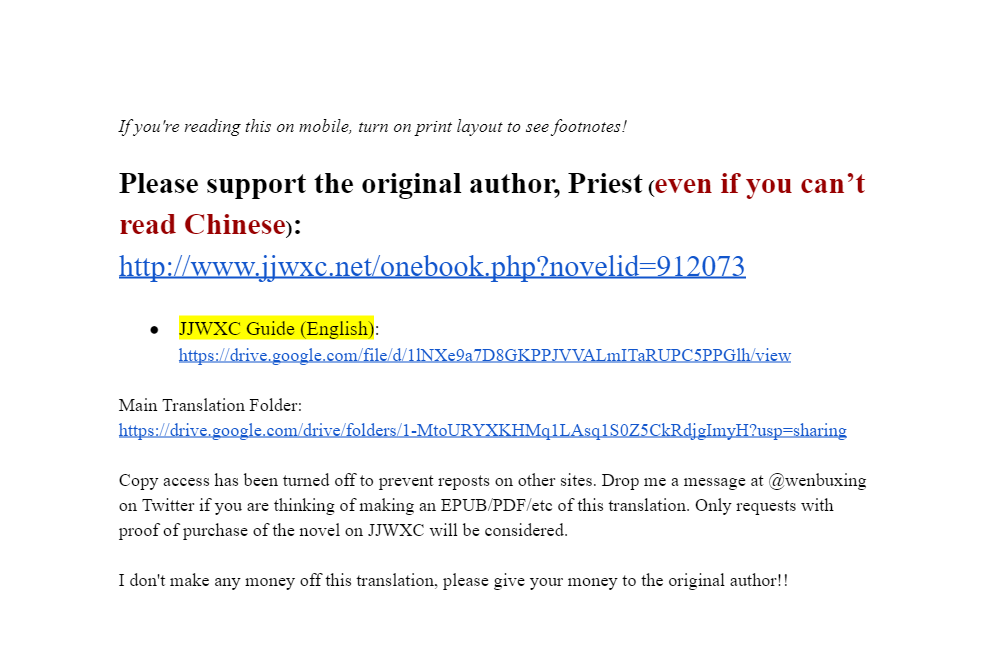

So, a cfan may translate a novel and expect only a tip via ko-fi, or provide a pay-what-you-can link to download the novel, but they will strongly recommend that ifans buy the original novel, from platforms such as JJWXC, to “support the author,” even though an ifan is clearly not going to be able to read what they’ve bought.

Both cfans and ifans navigate a narrow strait where they have some limited freedom to do certain things but absolutely must not trip any official alarms in c-media: they can provide translations on individual blogs, but not on a platform such as wuxiaworld; they can sub entire episodes of reality shows and allow private downloads, but absolutely must not upload them on YouTube. A cfan’s work might be un- or underpaid, but it remains independent of what a media conglomerate’s clout can do to the work.

Within these strictures, and standing on somewhat unequal ground, cfans and ifans come together, because fandom is fundamentally a labour of love that is driven by and paid for with enthusiasm.

——

Tianyu: The free labor done by cfans—translations, information sharing, and writings—reminds me of the many local volunteer translators who made Chinese subtitles for foreign, especially American, TV shows and films. Known as “subtitle teams” (字幕组), they’re highly organized and selective, emerging amid a media environment in which Chinese viewers couldn’t access the latest foreign shows due to both regulatory and language barriers. Most recently, however, the government has cracked down on Renren Yingshi, one of the largest subtitling sites, on charges of piracy—which would’ve been valid, as there’s almost no legal channel for anyone in China to access foreign shows that haven’t been formally imported and sanctioned by regulators.

If you haven’t, consider subscribing to Chaoyang Trap, a newsletter about everyday life on the Chinese internet. It’s a regular, usually fortnightly, exploration of contemporary China, one important niche at a time. We’re interested in marginal subcultures, tiny obsessions, and unexpected connections.

Paid subscribers get access to our special deep-dives and premium issues!

Sridala is a poet and writer of books for very young children. She lives in Hyderabad and on Twitter.

Tianyu Fang is a writer who grew up in Beijing but is hardly ever in Beijing.