This dispatch appeared in S01 Episode 5, along with Two-Way Mirror by Sridala Swami and “ZQSG for YYDS”: How Idol Fans are Made by Yan Cong. Cover illustration by Krish Raghav.

Tianyu: Zheng Yuanjie (郑渊洁) is one of contemporary China’s earliest—and most famous—children’s book authors. A former factory worker, his Shuke and Beita (舒克和贝塔) and Pipi Lu and Lu Xixi (皮皮鲁和鲁西西) series were mainstays for school kids in the 80s up until the 2000s. Shuke and Beita are two adventurous mice, the former a pilot and the latter a tank driver. They’re both friends with Pipi Lu, the stereotypical street-smart troublemaker in school; he’s quite the perfect partner-in-crime with his more bookish sister Lu Xixi.

Now 65 years old, Zheng still maintains an active online presence. On Weibo, he posts frequently about his many intellectual property infringement cases, and other legal violations he encounters in daily life. He’s accused a mall in Wangfujing of illegally occupying the tactile paving meant for the visually impaired. He occasionally goes on tirades against schools that ask students to buy children’s books for kickbacks from publishers. But he’s also known for interacting with his followers—a mix of adults who grew up reading his novels and younger fans of his online persona—and offering them life advice.

As a poster, he’s approachable and sometimes too frank—no surprise to his readers, since Zheng was well known for writing back to children, even back in the time of envelopes and handwritten letters. His interactions are at times filled with absurdist humor, self-referential jokes and “punchline” responses. Mostly, though, he’s an adorable boomer, either sticking to the good old 👍 and 🤝 emojis or replying with “Happy Monday” greetings.

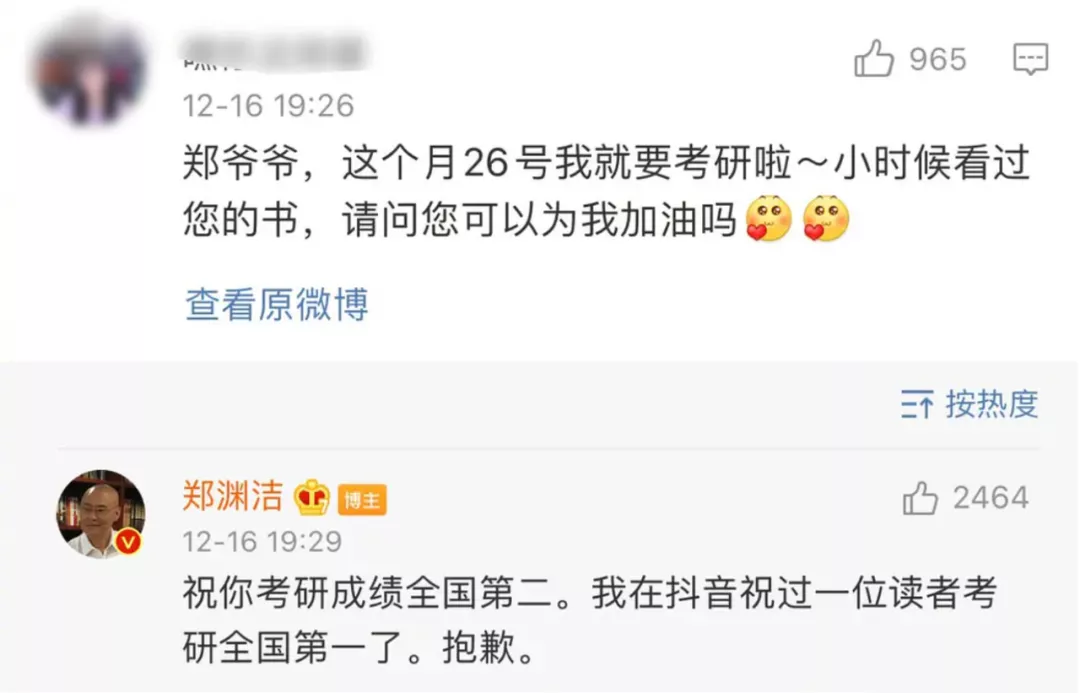

▲ “Grandpa Zheng, I’m sitting the graduate school entrance exam on the 26th. I read your books as a child. Will you cheer for me?”

“I hope you’ll get the second highest score in the country. I’ve already wished another reader to rank number one on Douyin—my apologies.”

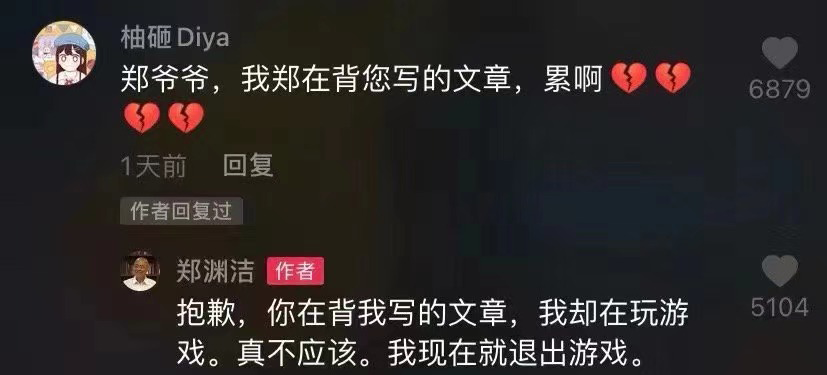

▲ “Grandpa Zheng, I’m memorizing an article you wrote. So tired!”

“Sorry. You’re memorizing my article while I’m playing video games. That’s not right. I’m quitting the game now.”

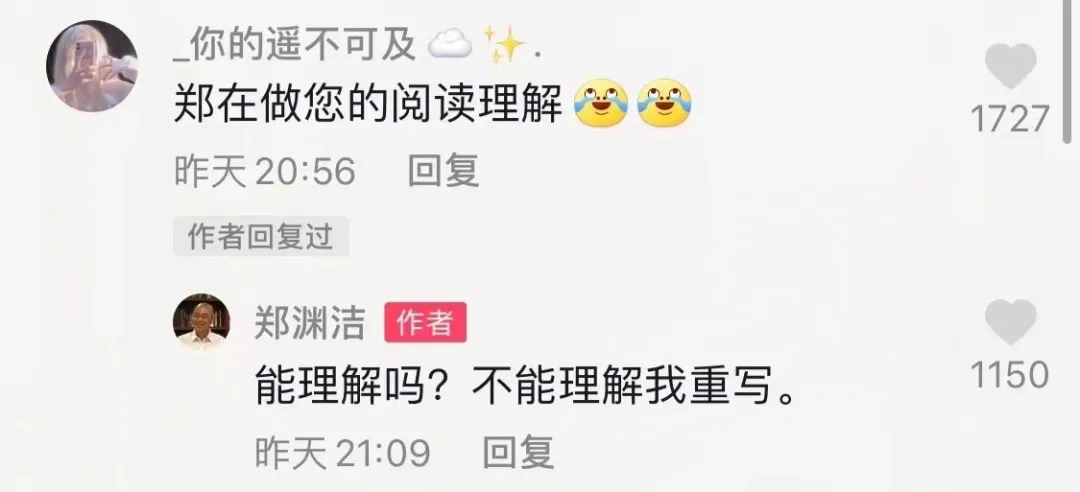

▲ “I’m doing reading comprehension for your article.”

“Could you comprehend? If not, I’ll go rewrite it.”

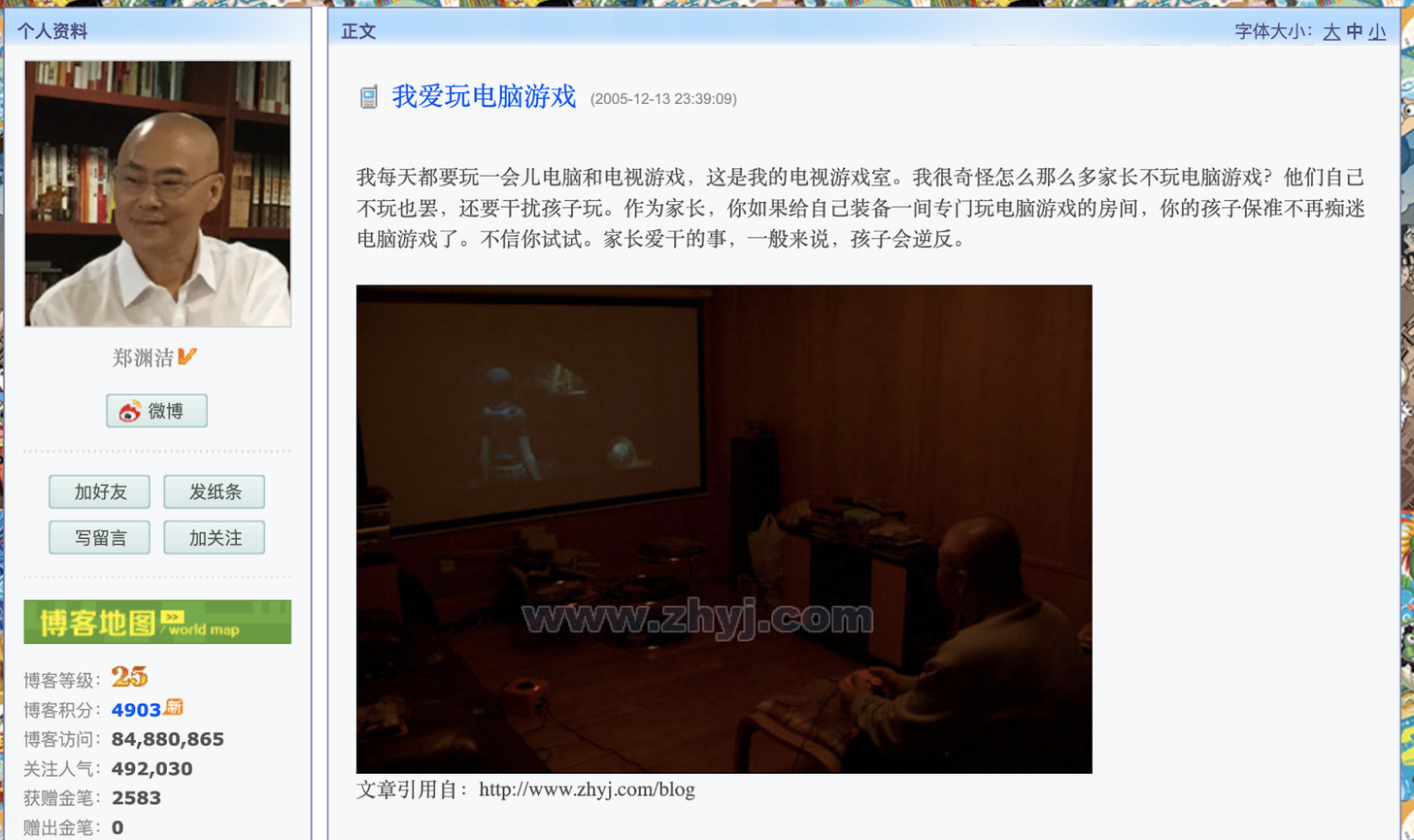

Zheng’s Weibo followers love his sincerity and bluntness, a craft honed through an obsession with social media that dates back to his 2005 blog. One of his early blog posts was titled “I love playing computer games,” in which he writes: “I wonder why parents don’t play computer games? It’s fine that they don’t play themselves—but they also prevent their children from gaming. As a parent, if you equip yourself with a room dedicated to computer games, your child will definitely stop being obsessed with it.”

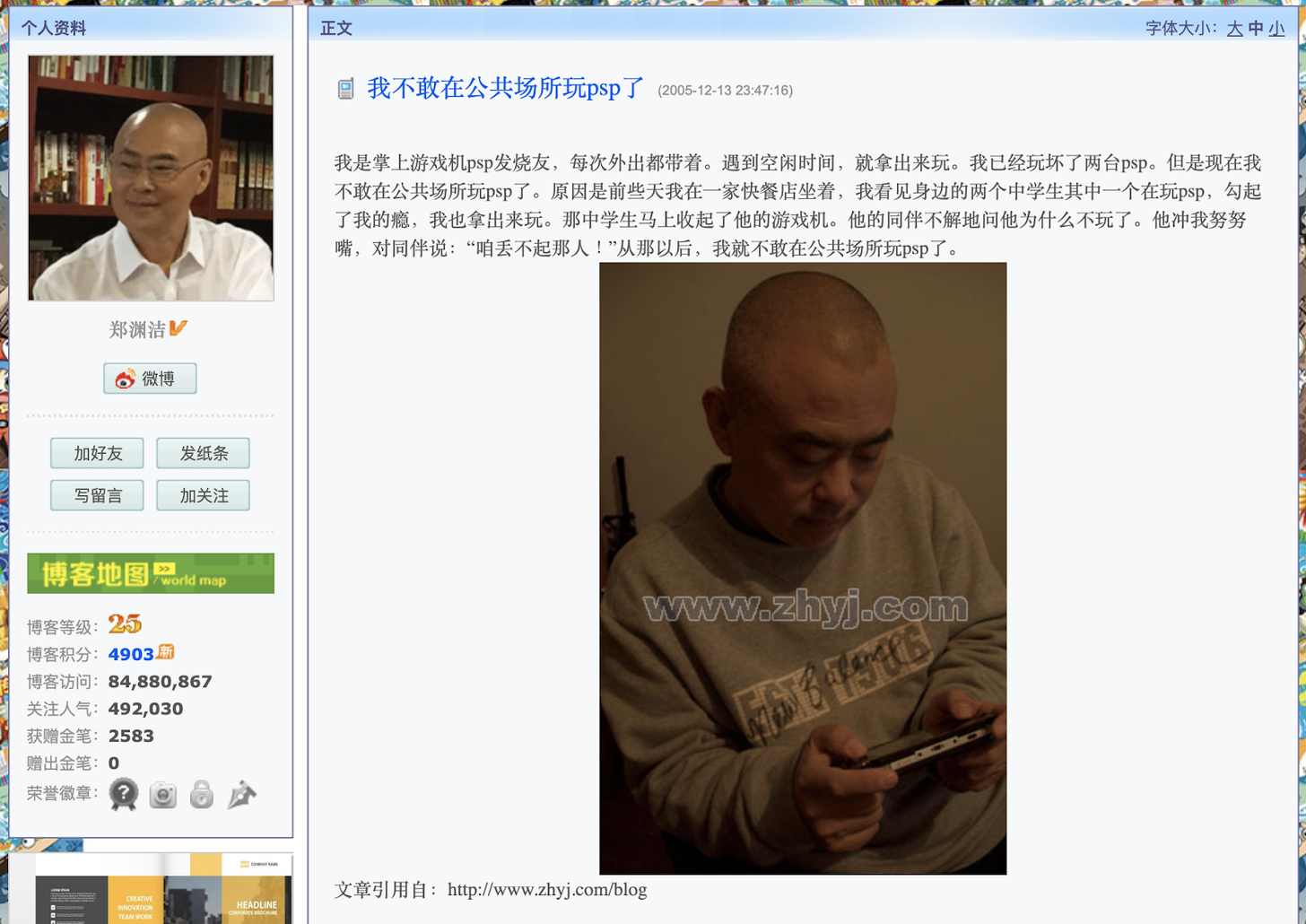

Just eight minutes later he wrote another post, writing that he saw a middle schooler with a PlayStation Portable (PSP) at a fast food restaurant. When Zheng, an avid gamer, took out his own PSP, the student was so ashamed that he put his device away. “Since then, I’ve been afraid to play PSP in public places.”

He published almost 2,000 posts on Sina from 2005 till 2017, until the platform (and blogging generally) faded from relevance and was replaced by Weibo. These posts range from random internet musings and excerpts from new stories to serious essays on education and writing (along with subtle references to sensitive political events: he wrote, in “Buying a Cellphone for the First Time,” that the first time he saw someone use a cellphone was a Japanese journalist at Tiananmen Square, in May 1989).

Zheng was a maverick. Though he is often called China’s “king of fairy tales,” he doesn’t write much about unicorns and mermaids—rather, most of his writings are interspersed with social commentary and political critique, cleverly veiled for a young audience. My first Zheng Yuanjie book, which I read as an elementary school student in Beijing, was 2006’s Pipi Lu and 419 Crimes (皮皮鲁和419宗罪). (the story of Yuan Lielie, a bacterium, helping Pipi Lu’s uncle solve crimes by attaching himself to suspects and eavesdropping on their conversations.) Zheng wants children to be aware not just of right and wrong, but what is illegal and how the law protects people —the novel itself was written as a legal awareness textbook of sorts for his own son Yaqi (郑亚旗). In the process, he also brings forward conversations that were once considered taboo—this was the first time I’d read about rape and sexual harassment in a book; other stories involved bribery and abuse of power by government officials.

Zheng is also known for his skepticism of China’s education system, often criticizing its test-centric nature. He was a grade school dropout - which he likes to highlight in interviews - and he decided to homeschool Yaqi. (Zheng gave signed copies of his books to every child in Yaqi’s class who got poor scores on exams, writing, “you will do great things in life.”)

He wasn’t immune from criticism. In 2001, Zheng came under scrutiny after Benny Sa (撒贝宁), host of the CCTV program Legal Report (今日说法), said his books were “not suitable for children,” due to mentions of sexuality and sex. Facing public pressure, and in protest, Zheng said he would not publish his new series of novels until 100 years after his death.

Looking back, it was Zheng’s literature, with its clear-eyed acknowledgement of societal fault lines, that made me realize it was acceptable to talk publicly about justice, to challenge norms, and to question authorities. Yet Zheng is no longer the national best-selling author that he used to be, and his past work lives on largely due to a sense of nostalgia. While he remains a child at heart, accommodating young readers of different generations turned out to be difficult. His public image gradually transitioned from a children’s writer to an online writer during China’s blogging craze in the late 2000s, as he continued to engage with his earlier readers as they became grown-ups. A blunt discussion about sex in children’s books may have been taboo in China in the 1980s—but his readers from that era have now become parents, and there are now new norms to be questioned and progress to be made.

But will there be another Zheng Yuanjie?

Another rebel figure in China’s literary sphere was Han Han (韩寒), the rally driver who (also) dropped out of school to write novels. Like Zheng, he was a blunt writer, and popular blogger, unveiling the “dark side” of Chinese society. He pulled no punches, frequently raising socially and politically taboo topics, albeit to a different demographic from Zheng.

Neither writer would be considered a dissident. While Han was a vocal critic of internet censorship in the early days of social media “management,” he wasn’t the kind of writer who called for drastic political changes—he was, for instance, skeptical of China’s democratic transition. But as public figures, both contributed to the liberalization of the Chinese discourse.

It’s almost unimaginable to think that his provocative literature would be published today. This rebel culture that Zheng and Han once represented—the constant pushing of boundaries and speaking truth to power—gradually faded away from the “mainstream” of the Chinese web in the second half of the last decade. And for better or worse, that’s something to be lamented.

Caiwei: I first read Zheng at age 7. My old, snappish, and pedantic father, who shared his contempt of authority and cynicism, but had that same heart of gold, recommended Zheng as a children’s author who “never talks down to kids.” It rings truer when I revisit Zheng’s work as an adult—his stories, packed with harsh tell-alls of the adult world, don’t shy away from topics like the bureaucracy, the stock market or sex, often cased in commentary and dripping with biting sarcasm.

Compared to other writers of his generation (including “China’s J.K Rowling” Yang Hongying (杨红樱), who sees children as reduced, "unfinished human beings", and Cao Wenxuan (曹文轩), who’s made a name for himself by personifying the innocence and beauty of children), Zheng doesn’t see children as “lesser” human beings, but rather as complete and untouched, crackling with powerful potential.

Echoing Chloé Zhao’s recent Oscar acceptance speech, in which she says that "people at birth are inherently good," I think Zheng is a true humanist. He has faith in the intelligence and heart of children, treats them with equal (if not more) respect and appreciation, and is thus welcomed in turn by young readers. I’ve been adulting for a while, but I still constantly think of Zheng’s reminders to not be corrupted by adulthood itself.

Xuandi: When I was little, Zheng’s books were among only a few 闲书 (books other than textbooks) that we were allowed to read in our spare time. And the knowledge in his writing was truly impactful. A friend told me that only after reading Zheng’s books did she realize that her elementary school teacher’s behavior was inappropriate and could constitute sexual harassment.

Zheng writes intentionally for young readers, while Han, who is often brought up alongside “Hooligan Literature” writer Wang Shuo (王朔), has this untamed, sometimes vulgar tone in his work. However, they both share this literary tradition of expressing an idea through constructing a fable. I often think about how a Chinese journalist called his work “fable-writing” (寓言家式的写作)—in order to skirt censorship, you have to write in a discursive, metaphorical mode. Seen in that light, maybe the spirit of Zheng or Han never dies away.

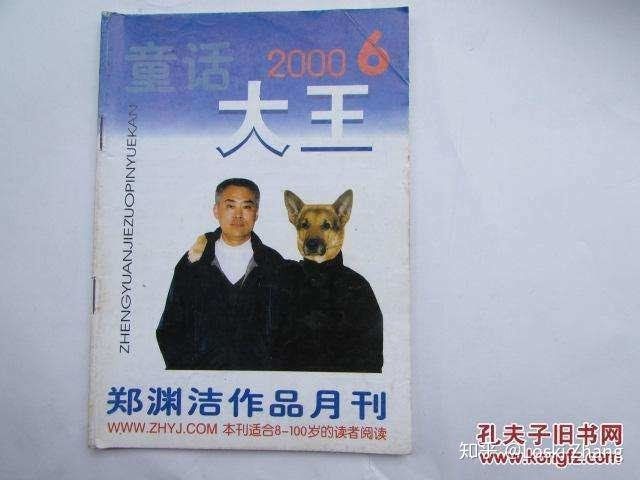

Boyuan: Zheng Yuanjie always had a big ego. He claimed that he could not tolerate his works being set beside other writers’, and that’s how his popular monthly publication, King of Fairy Tales (童话大王), came into being. Being the sole author of a decades-long literary magazine became another thing he loved to boast about.

I enjoyed Zheng’s work primarily in the late 90s and early 2000. That's when he had ambitions to pivot from kids-lit/YA to something resembling “modern fantasy”, some of which were intended solely for adults but still published under the King of Fairy Tales imprint.

And as Tianyu mentioned earlier, this new attempt received backlash from education experts and state media. His big ego allowed him to drop the plan, and Zheng went back to being the gentle grandpa.

If you haven’t, consider subscribing to Chaoyang Trap, a newsletter about everyday life on the Chinese internet. It’s a regular, usually fortnightly, exploration of contemporary China, one important niche at a time. We’re interested in marginal subcultures, tiny obsessions, and unexpected connections.

Paid subscribers get access to our special deep-dives and premium issues!

Tianyu Fang is a writer who grew up in Beijing but is hardly ever in Beijing.

Caiwei Chen is a writer, journalist and podcaster. She cooks with boxed ingredients but tries to finish all her dishes with a gourmet touch.

Xuandi Wang is a writer who grew up in Zhejiang. His professional skills include, but are not limited to, lurking and gawking.

Wang Boyuan is writer at PingWest. He was born and raised in Xi’an—the “magically surreal” city acclaimed by Weibo folks—where he is now based.